Backtrack: Norman Norell

An eight-foot round bed, walls in gold-painted burlap, and pagoda-style trim over a boy’s bedroom windows at 4160 North Pennsylvania Street in 1914—these were among the early clues that Norman Levinson, 14, was destined for a place in the world of style.

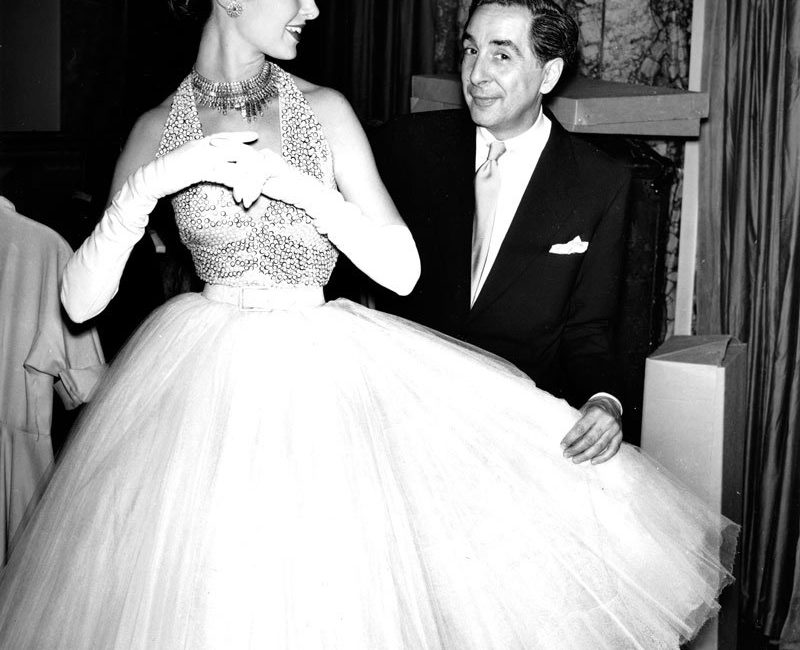

By the time he suffered a stroke and lost consciousness on October 6, 1972—the same day that New York’s Parson School of Design opened a major retrospective of his work—there was little dispute that Noblesville native Norman Norell, as he was by then known, had gone on to become the first American to rule the fashion scene.

The first designer to win the Coty Award, fashion’s equivalent of the Oscars, when it was introduced in 1943. The first named to the Fashion Hall of Fame, in 1956. The first so famous he slapped his name on bottles of perfume, with sweet success of more than a million bucks that first year, in 1968. And in the inaugural group of designers to earn stars on the Fashion Walk of Fame in Manhattan when it was cemented in 2000.

What shot Norell to such lasting stardom in the often-fickle world of style? Simplicity. His “no-neckline dress,” as he would later describe a signature look, had “no crap on it … no collar, no frills.” Circa 1928, it was youthful and crisp. The fashion industry and everyday women loved it.

But what really set Norell apart was his attention to ready-to-wear clothing, a much cheaper alternative to couture, which still dominated fashion at that point. He spent the next decade perfecting off-the-rack looks that would finally wrest the fashion industry away from Paris’s longtime grip. By the time the world was at war and Paris was occupied by the Nazis, submarining its fashion scene, Norell was ready in 1941 with a full fashion collection—the first ever from an American designer.

During those war years, New York became the fashion universe, and Norell its mild-mannered god. But even then, and in his ensuing decades of success, he never lost his sense of proportion. By 1972, he was telling The New York Times, “Fashion is getting to be less important. It’s getting to the place where it should be.”

Norell had a stroke the next morning and died 10 days later. The funeral drew oodles of designers and models, and the obituary shared the front page of the Times with that of another historymaker: Jackie Robinson. Nephew Alan Levinson said all the attention probably would have embarrassed Norell: “He never liked any fuss.”