At 25, Is Circle Centre Already Over The Hill?

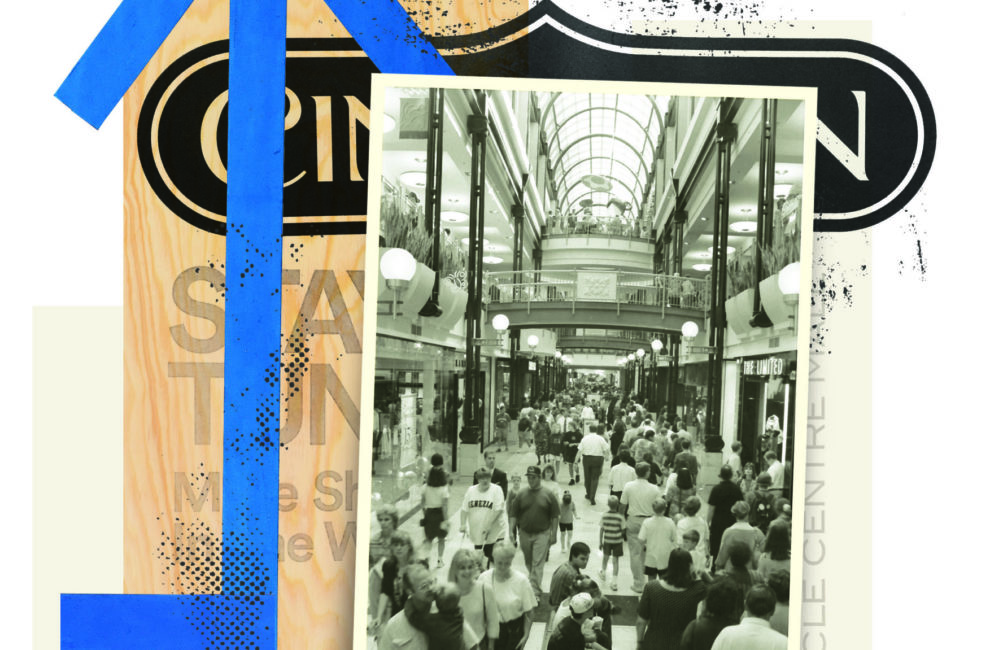

Circle Center photo courtesy Banayote Photo Inc., Indiana Historical Society

Circle Centre missed its moment. When Mayor William Hudnut pitched the idea of a downtown mall to the Simon brothers in 1977, mallrats were a thriving breed. By September 1995, when Circle Centre opened, the indoor mall boom was over.

But it started out promising. In 1979, Melvin Simon & Associates unveiled a plan for a $100 million shopping mecca between Meridian Street and Capitol Avenue that would connect the two retail titans of downtown, L.S. Ayres & Co. and William H. Block Co. Hudnut saw Circle Centre as a crucial part of his vision for a vibrant downtown—along with a convention center, hotels, and a stadium for a potential NFL team.

So what took 16 years? Property squabbles, funding shortages, and a recession in 1990. But buildings had already been torn down and large holes had been dug at the construction site. (City planners would later say that digging those holes was the best thing they did, because otherwise the city might not have been motivated to finish the project.) Six years after construction began, Circle Centre opened. By that time, Ayres and Block were long gone. Nordstrom and Parisian were the opening-day anchors.

And, for a while, it was novel. Hudnut’s successor, Stephen Goldsmith, says it was the first time in his life that downtown Indianapolis was alive. “The fact that you could come downtown to have dinner or shop in stores was a big deal,” he says.

The mall outlasted its competitors. Between 2007 and 2009, one in five of the largest 2,000 malls in America closed. Yet Circle Centre continued to turn a profit.

Then the 2010s hit. In 2011, Nordstrom closed because its new Fashion Mall location had slashed downtown sales. Then Carson’s (Parisian’s replacement) shuttered in 2018 despite city tax subsidies to prop it up, leaving the mall without an anchor.

But this thing wasn’t going down easily. The Indianapolis Star moved into the old Nordstrom space in 2014, and Circle Centre finished the next year with what was at the time a record profit—$11.2 million, up 30 percent from 2014. In 2018, it was 94 percent leased, according to Simon’s most recent report to the city, the mall’s landowner. It counts nearly 100 stores, a high school, a comedy club, bumper cars, and a cigar lounge, and remains profitable (at least pre-pandemic—it brought in $13 million in 2018). A multimillion-dollar spruce-up is underway.

Yes, it’s due for a rethink. “It was never intended to last as long as it’s lasted in the exact same configuration,” Goldsmith says. “It’s been time for a creative refresh for the mall for a while now.” Urban planners see a way forward. Eric McAfee, the author of the development-focused blog American Dirt, says Circle Centre needs to embrace pop-up stores, short-term leases for small businesses, and flexible uses of vacant spaces for pandemic-resistant services like socially distanced learning, day care, and pet boarding. “We need to rethink how we engage in commerce,” he says.

Like, say, Bottleworks. The first phase of the $300 million development on Mass Ave is slated to open in December, catering to Gen Z-ers with Instagrammable destinations like duckpin bowling and an art cinema. Now it remains to be seen if Circle Centre can cultivate the same buzz—even amid a pandemic.