Backtrack: Pi Day

It was kind of like trying to legislate the Earth into being flat, or decreeing the sky was no longer blue. But in 1897, Indiana came perilously close to legally changing the mathematical value of pi.

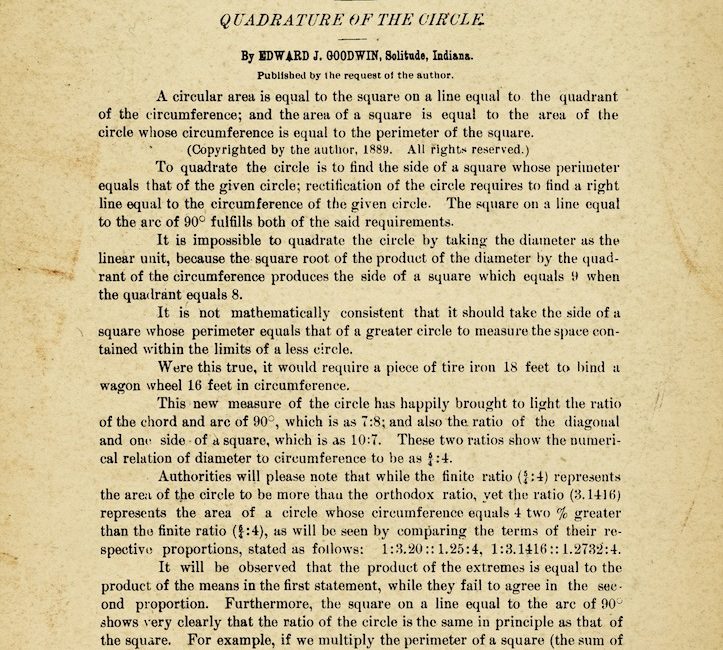

Professor C.A. Waldo taught math at Purdue University. He shot down a bill that would have legally redefined “pi,” using the theory of amateur Edward J. Goodwin in a nationally published article.Image courtesy Purdue University

Edward J. Goodwin was a Hoosier physician who liked to do math in his spare time. He decided to tackle the (nonexistent) debate on whether you could square a circle. Pi is the ratio of a circle’s circumference to its diameter, which we all know as the infinite number 3.14159265 … and so on.

Pi has been recognized as a constant for almost 4,000 years, though its value has changed slightly over time. Ancient Babylonians and Egyptians had rough approximations of pi, and the first calculation of it as a literally endless string of digits beginning with “3.14” was made by Archimedes sometime between 287 and 212 B.C.

Fast forward to 1882, and German mathematician Ferdinand von Lindemann proved that pi is transcendental, or irrational. His method established that the classic Greek puzzle of squaring the circle—that is, constructing a square with an area equal to that of a given circle—couldn’t be done.

But Goodwin set to work proving that yes, it could—as long as you, uh, changed the value of pi to 3.2. In 1894, he got the American Mathematical

Monthly, a new journal, to print his work (albeit with a disclaimer in the article that it was “published by request of the author”).

Goodwin was pretty confident in his formula—so much so that he copyrighted it, thinking everyone would want a piece of the pi theory. He planned on collecting royalties from anyone who wanted to use his proof. But he would let his home state of Indiana use the formula for free—sort of.

Professor C.A. Waldo, a mathematician who happened to be inside the Statehouse just as the Indiana Pi Bill was coming up for a vote … was stunned by what he saw.

The amateur mathematician told the state that if the legislature would adopt his new “truth” as state law, they wouldn’t have to pay him any royalties. He persuaded Representative Taylor Record to bring the bill to the House in 1897. It passed unanimously.

Next, the bill proceeded to the Senate’s Committee on Temperance, where it also passed. By now, the news that the value of pi could possibly be changed had garnered national attention and mockery.

Enter Professor C.A. Waldo, a mathematician who happened to be inside the Statehouse just as the Indiana Pi Bill was coming up for a vote. While waiting to secure some state funding for his school, Purdue University, Waldo read the bill, and was stunned by what he saw. He managed to get in front of a group of senators, and explained why Bill No. 246 should be swept aside indefinitely—and into the annals of history.