The Changing Face Of Indiana Avenue

“Shirley! Shirley! Somebody tried to kick the doors in!”

Pastor Louis Parham studies a broken frame in his office at Bethel AME Church, the city’s oldest African-American place of worship. Shirley Jones, a member and trustee, rushes in to see.

Parham sighs, resigned. A would-be robber is the least of his worries this February morning. Sitting on his desk are three proposals from developers eager to get their hands on this prime piece of Canal Walk property. And for the first time in the 147 years the congregation has occupied the spot, the members are seriously considering selling.

Bethel can handle its expenses just fine, clarifies Parham. The problems run deeper, though, down to the foundation—or lack thereof. In existence since 1836 as part of the Underground Railroad, Bethel did not build its church upon a rock when it moved to this location in 1869, but on the bare ground. Today, the National Register of Historic Places site tilts, sinks, shifts, ready to crumble unless $2 million for repairs shows up soon.

A last-ditch capital campaign last fall yielded a lot of promises and a $100 gift card. Mortgage debt prevents Bethel from taking on new loans. And those are just the financial challenges. A century ago, Bethel acted as a social hub for Indiana Avenue, the center of the city’s African-American culture. Up the street, Madam C.J. Walker’s beauty empire thrived in an elaborate headquarters. Lockefield Gardens—the country’s first high-rise public housing—debuted in the mid-’30s with hot-and-cold plumbing, a luxury. Weekends pulsed with jazz coming from the clubs and bars and restaurants along the stretch. At the Avenue’s height, Bethel hosted up to 500 members.

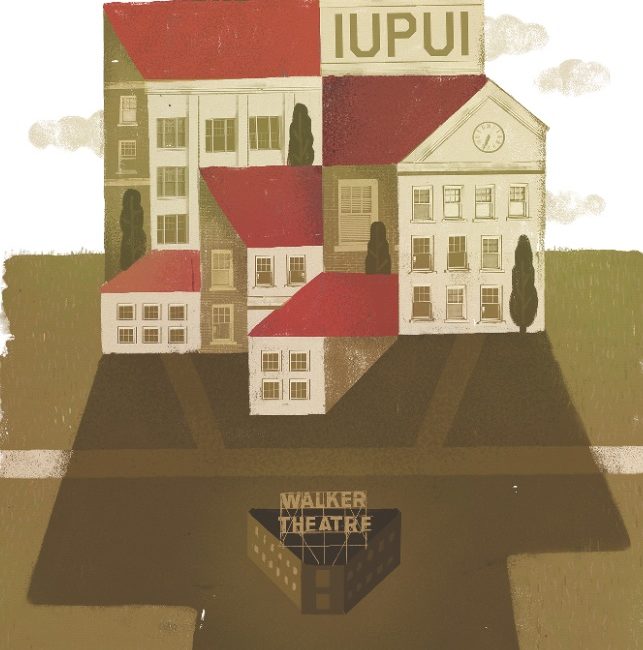

But as desegregation, economic hardship, and other factors unraveled the fabric of the Avenue, Bethel became one of the last echoes of that golden age. With nearby IUPUI’s growth, demographics also changed. Bethel’s worship style no longer appeals to the students and young professionals bringing density back to the area. The average congregant age is 64. Membership has dwindled to 149. And now Bethel’s home is dangerously unstable. All of which make those proposals on Parham’s desk harder to ignore.

The pastor grimaces as he explains the predicament: “There’s a truly heartfelt desire to stay here. That’s what the heart says. The intellect says, You can’t stay.”

Long known as a commuter school, IUPUI’s population now skews to the typical post–high school student, one seeking a more traditional college experience—on-campus or nearby housing included. The university has expanded its residential options, and in the past few years, developers have swooped in to take advantage of the shift, too. Mixed-use apartment complexes began shooting up in the vicinity, from The Avenue at Indiana Avenue and 10th Street to the 9 on Canal, just up the waterway from Bethel. Few view the wave of growth as a bad thing. But a fraught history between IUPUI and the Avenue complicates the issue.

In its early-to-midcentury heyday, the district shimmered with activity. “It is hard to explain how it felt in 1940 for a young eighteen-year-old man-child to walk down Indiana Avenue on a warm summer evening, dressed in a tailored suit, shoes shined, and a Duke of Wales shirt and tie, with his friends at his side,” writes Thomas Howard Ridley Jr. in his memoir, From the Avenue. “There was live jazz all around us and pretty, smiling girls checking us out. At the time, we didn’t think life could get any better.”

Blacks and immigrants gravitated to the land near the White River because it was affordable—whites avoided the malaria-prone area. But from that cheap real estate sprang beauty shops, tailors, clothing stores, churches, restaurants, grocers, the Indianapolis Recorder, and clubs such as the Sunset Terrace, which drew big acts like Duke Ellington and local jazz talent like Wes Montgomery.

David L. Williams, an IUPUI adjunct professor of Africana Studies and author of Indianapolis Jazz, grew up in Lockefield. Now he teaches in buildings erected where he used to play. “We were so insulated, we didn’t really realize the total effect of segregation,” says Williams. “It was a world within a world.”

Dorothy Pipes, an 89-year-old raised on Blake Street in a home later sold to IUPUI, recalls that same tight-knit community: “You never went on the Avenue when you didn’t see somebody you knew.”

But as residents and businesses began moving north in the 1950s, the population loss led to more closures. Fear and distrust spread as the expanding campus collaboration between Indiana University and Purdue University began buying up homes, and the city rezoned swaths for commercial use to aid the growth, at times using eminent domain. Historic buildings were lost to the wrecking ball and highway construction. “People began to react, but as in so many things, it was too little too late,” says Wilma Moore, senior archivist of African-American history at the Indiana Historical Society.

“This whole university displaced the community,” says Andrea Copeland, an assistant professor in IUPUI’s library and information science department who is working with Moore, Indiana State Museum curator Kisha Tandy, and Bethel historian Olivia McGee-Lockhart to digitize the church’s records. Copeland hopes the school will put the students’ environs in better historical context. In his installation address last November, chancellor Nasser Paydar noted IUPUI’s responsibility to preserve the “rich history of the people—particularly African Americans—who once lived and worked” nearby. But currently, the university does not formally discuss that history with students when they arrive on campus.

“I would like to see Indiana Avenue and the African-American heritage story become part of the university’s story,” Copeland says, “such that every person that works here, goes to school here, knows that history and realizes the importance of it to the place.”

Thomas Howard Ridley Jr., spry at 93, gives tours of the Walker headquarters, or as it’s known these days, the Madame Walker Theatre Center. On a recent morning, he ambled through the ballroom, recalling when he and his late wife would come dancing there for 39 cents. You can still cut a rug at the Walker at monthly “Jazz on the Avenue” nights, but the site has not hosted an arts season since executive director Kathleen Spears departed last May, reportedly frustrated by a slow-moving board of directors.

Malina Jeffers, who served as the Walker’s director of marketing and programs for three years, also left disheartened. During her time there, Jeffers felt there was an environment of fear when it came to IUPUI. “When I would say things like, ‘They don’t have a theater on campus, let them have it.’ No! If we give them an inch, they’ll take a foot. They’ll do it again,” says Jeffers. “And [I was] constantly trying to explain, ‘This is not 1927. This is not black row. And although that was amazing, and although we want people to know that and respect that, it’s not where we are right now. We’re on a college campus.’”

Since then, IUPUI-affiliated members have served on the Walker’s board of directors, and recently hired interim executive director Anita Harden attended, taught, and served on boards at the school. “Part of me has said, [The growth] is a great thing for IUPUI,” Harden says. “Another part of me has said, They are wiping out some history and that’s not so good.” She looks around the Walker’s boardroom. “They won’t wipe out this.”

To ensure that future, the Walker has brought on Greenwood-based business consultants Johnson Grossnickle & Associates to lead a strategic-planning process to figure out how the Walker can “best serve the city and be true to its legacy at the same time,” says Harden, who foresees targeting students as a key part of the landmark’s plans no matter what. “There’s no reason why it should be IUPUI versus us,” she continues. “There’s no reason why we can’t work together or develop this together.”

District 15 councillor Vop Osili—an architect who designed several Avenue buildings and joined the Walker’s board last year—agrees. “On a Friday night, where would some of these guys be going, and can we maybe have them doing whatever that is in Fountain Square, right here?” says Osili. “Some of that is wiping away this thought that this is a building for African Americans. Let’s bridge that, and then say, This is a building for our communities who are here—all of us.”

Indianapolis’s 1821 plat had four spokes radiating from the city’s center. In recent years, those eastern avenues, Massachusetts and Virginia, have flourished, thanks in part to the Cultural Trail. The bike-and-pedestrian path barely skims their northwest counterpart, Indiana Avenue, at this point, but that could change: The trail may be extended up to 16 Tech, a technology and research campus being constructed at the top of Indiana Avenue.

Development at the northern end of the corridor has been both a blessing and a curse to historically African-American districts like Ransom Place. Recently, a group that included neighborhood-association president Paula Brooks filed a suit, later dismissed, to prevent a 27-unit housing project from going up in Ransom Place, citing a spike in density the area—already crunched for parking—can’t handle. “We’re really not anti-development,” says Brooks, who estimates students compose around 40 percent of the seven-block pocket’s makeup. “But we don’t want something that’s going to further dilute the heart and soul or character of Ransom Place.”

Farther south, Cedarview Management, which is also involved in the disputed Ransom Place project, salvaged some of that Avenue history by working Willis Mortuary—once home to Indiana’s first African-American certified mortician—into the blueprints for its 632 MLK apartments instead of demolishing it. The complex’s design will also mimic the exterior of the Walker, next door. Cedarview may retool plans for their two Ransom Place developments, says Suzanne O’Connell, the company’s vice president of real estate, once they assess 632 MLK’s success.

Brooks says the students in Ransom Place’s single-family homes “were really good initially, because it allowed a wider diversity of the population. But there’s a balance.” In the next two decades, she worries the neighborhood will become a “de facto IUPUI campus”—possibly facing the same bleak future as Bethel.

Just across Fall Creek from Ransom Place, 16 Tech’s planners envision a new kind of partnership with the Avenue’s legacy institutions—one that could prove key in the push to make the corridor vibrant once more. Betsy McCaw, president of the 16 Tech Community Corporation, successfully sold 16 Tech to nearby neighborhoods as an economic anchor for the Avenue; residents even showed up at City-County Council meetings to testify on its behalf. 16 Tech will also dole out a community investment fund to subsidize infrastructure, workforce, and education initiatives, as prioritized by the neighborhoods.

“In an ideal world, [the Avenue] gets returned a little bit to its history,” McCaw says of the growth she believes 16 Tech could generate. “I would love to see it become kind of a Mass Ave, but a jazzy Mass Ave. I think it’s ready for it.”

16 Tech wants to be at the table, McCaw says, when it comes to how Indiana Avenue develops. But so far, the major stakeholders have never come together as one group to advocate for the corridor’s future. Brian Sullivan, managing partner at Shiel Sexton and a longtime Canal resident, believes the area needs to form a redevelopment commission and hammer out a master plan. The time is right, he says, for the Avenue to be “the next big thing downtown,” but the strip’s players must work together—and the plan should incorporate the Avenue’s history.

“In my mind, Mass Avenue is now what Indiana Avenue was,” says Olivia McGee-Lockhart, the Bethel historian. “But many of the buildings in our area have been torn down. You can’t refurbish what’s not there.” Jazz historian Williams agrees: “The Avenue was the people, the entertainment, the buildings, the legends—all that’s gone. And when Bethel goes, that’s the nail in the coffin.”

“Forget the former things. Do not dwell on the past! See, I am doing a new thing!” Pastor Louis Parham’s voice crescendos on the last Sunday in February as he preaches in Bethel AME’s sanctuary, its woodwork, trellises, and imposing 1905 organ distracting from the peeling ceiling and wrinkled carpet. Less than 50 people, mostly African Americans, clap and sing in the pews. But Parham’s sermon foreshadows the changes to come. “Our forward momentum as a people can become slowed and even stagnant if we dwell too much on past accomplishments,” he says. “Some of us, though, are still looking back at the times when you had to get here a half-hour early in order to get a seat in this great place.”

The crowd titters. They realize those days are over. And soon, their time in this building will be finished, too: Sun Development & Management Corporation, a local company specializing in hotels, struck a deal in April to buy Bethel. Chairman and CEO Bharat Patel wants to turn the building into a hotel, and has agreed to keep the bell tower and facade in place as part of the agreement.

But, as Parham puts it, the building is not Bethel. The people are the church. They will find a new home. And so back at the Sunday service, he urges his flock to fear not. “It’s important that we don’t get trapped in the past, and we don’t get scared about the future,” he preaches. “If you think God is finished doing great things for Bethel, you better hold on to your hats.”