Curb Appeal

Q: Why do some downtown streets have parking meters while others are free?

Jacob P., Indianapolis

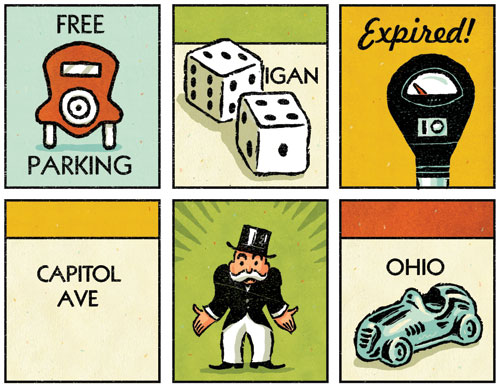

A: There are downtown city streets with free parking? If that’s what you’re implying, then The Hoosierist begs you to enlighten him. According to Marc Lotter, communications director for Mayor Greg Ballard, pretty much every bit of curbside asphalt in the Mile Square requires coinage for parking. And it’s not just to wring every last cent of revenue from motorists. Well, it’s not all about that. It’s also to keep commuters from monopolizing spaces from dawn to dusk, to the detriment of nearby businesses needing easy access for customers. “It encourages turnover and discourages long-term parking during the business day,” Lotter says.

But while downtown Indy is extremely meter-intensive, the rest of the city (except for Broad Ripple) is one gigantic free-parking zone. That’s because most businesses install these things called parking lots, which make street spaces redundant. The Broad Ripple meters are there for pretty much the same reason as the downtown ones—to keep space hogs from tying up precious spots for hours on end. And to make some fast cash, of course. If you’re wondering just how much all those nickels and dimes (and now, credit cards) amount to, consider this: From March to June of 2011, the city netted $498,000.

Q: Is it true that Colonel Sanders was from Indiana?

Susan O., Noblesville

A: Attention, youngsters. The old guy with the string tie and funny beard on the KFC signs isn’t a marketing-agency invention like Tony the Tiger or Justin Bieber. It’s the true-to-life visage of Col. Harland Sanders, the chain’s founder and creator of its famous “11 herbs and spices” recipe. Sanders’s company is today headquartered in Louisville, and his mortal remains rest nearby in that city’s Cave Hill Cemetery. He became a colonel in 1935, when the governor of Kentucky recognized his groundbreaking contributions to the field of Unhealthy Fried Things by making him an honorary Kentucky Colonel.

Given his pedigree, most people think he’s a native of the Bluegrass State. Well, most people are wrong. Sanders was born in Henryville, Indiana, right across the river from Louisville. Incredibly, the tiny municipality has never exploited this tourism windfall. Might The Hoosierist suggest a Harland Sanders Festival, a statue in the town square, or perhaps sprucing up his boyhood home and turning it into the Harland Sanders Birthplace Museum and Gift Shop?

Or if all that is too much bother, just get a Kentucky Fried Chicken franchise. Which, incredibly, Sanders’s birthplace also lacks.

Q: Does the Eagle’s Nest on top of the Hyatt still rotate? How do they do that?

Peter L., Indianapolis

A: How times change. When this gigantic movable feast first got up to speed back in 1977, it was a huge deal. Because during the 1970s rotating restaurants were all the rage, right along with roller discos, stagflation, and avocado-green kitchen appliances. Today the cachet isn’t nearly as great, but the Eagle’s Nest keeps right on turning. Very slowly. According to Jeff Stewart, director of food and beverage for Hyatt Regency Indianapolis, it takes between 45 and 75 minutes for the eatery to make one revolution. No, you can’t crank it up so high that tables start flying out of windows. Since the entire works is powered by a puny ¾-horsepower motor, the “speed” settings range from Slow to Super Slow to Probably Moving. The restaurant can rotate in either direction, but only during business hours. “We turn it off at night, after we close,” Stewart says.

Q: I love the colorful designs IPL puts in its windows during the winter. How do they decide which to do, and who pays for it? After all, IPL is a public utility.

Rachel A., Indianapolis

A: If you think that IPL burns a lot of wattage by using its windows to create, say, giant American flags or Colts logos, think again. Back in the old days (IPL has done its Christmas-tree window display for half a century), the effect was accomplished as one would expect—by having someone with a building schematic block out which windows needed to be illuminated, then making sure the right offices left their lights on after hours. But these days a computerized, energy-sipping LED system on the windows’ exteriors does it all. “With six clicks we’re able to change the lights on the building,” says IPL corporate communications chief Crystal Livers-Powers. “We’re able to do so much more, and we have a lot of fun with it.”

It’s also less of a hassle for workaholic electric-company employees. Since the LEDs sit outdoors, late-working junior execs can leave their lights on without, say, screwing up the giant red heart that’s displayed around Valentine’s Day. All they have to do is close their blinds.

Q: Can the public ride the monorail between Methodist and IU hospitals?

Kim K., Carmel

A: The IU Health People Mover is free to all comers, but the “train of the future” turns out to be pretty darn slow. The monorail makes frequent stops at various medical facilities, running on a 1.4-mile elevated circuit. The setup was built so that patients and staff traveling from one facility to another didn’t have to fight downtown traffic in their cars.

Not that the monorail doesn’t have quirks of its own. Some passengers, noting the jittery ride, call it the People Shaker. Still, The Hoosierist thinks the train is awesome, because it reminds him of the Disney World monorails. Only better, because in between the tracks sit pneumatic tubes that allow samples to be passed from one hospital to the next. Next step: Expand the tubes throughout the city, making the age-old dream of rapid, to-your-door Chinese-food delivery a reality.

Illustration by Adam McCauley.

This article originally appeared in the November 2011 issue.