Madam C.J. Walker: Uncommon Drive

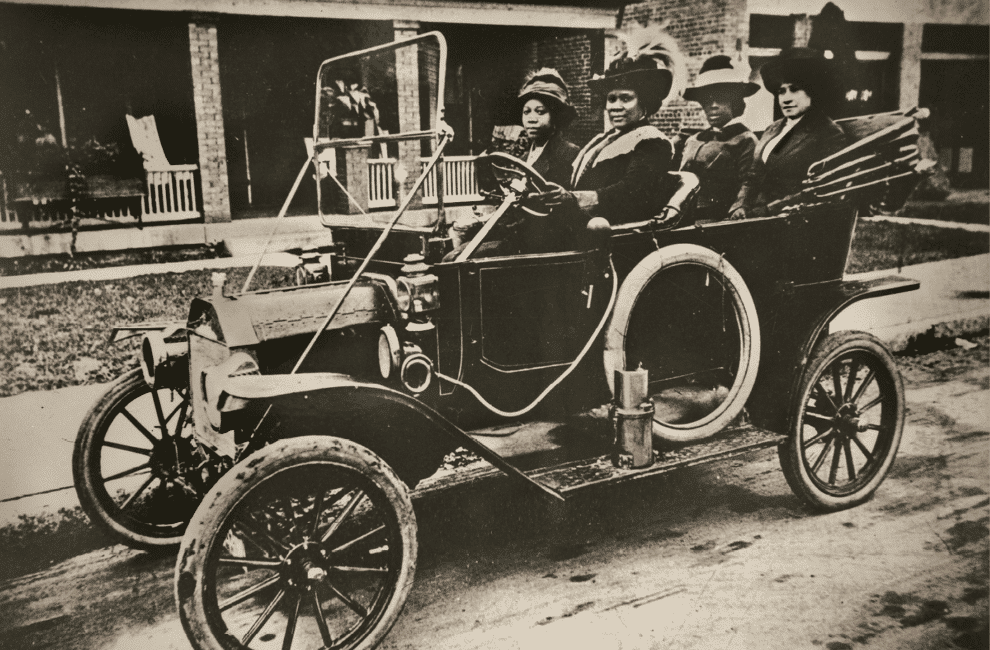

To the rest of the country, Madam C.J. Walker may have been a name on shampoo containers in African-American households. But it was here, perhaps, that the industrious and indefatigable pioneer loomed largest as an inspirational figure and community member. This image, of a resplendent Walker driving her own luxury car, says it all—a minority woman, the first child born into freedom in her family, sitting behind the wheel at a time when few women of any race drove.

Walker came to embody the highest level of achievement for a black woman from the post–Civil War South. Born in Louisiana in 1867, she built a business as a self-described “hair culturist” and beauty retailer in Denver, where she married a newspaper ad salesman. In 1910, she arrived in Indy from Pittsburgh already successful and quickly became a luminary in the city’s African-American community. She bought a house on West Street, near Indiana Avenue, which would soon become a prominent black neighborhood. There, she also rented rooms and operated her hair-product business.

As her earnings increased, so did her celebrity—and it didn’t hurt that she provided so many opportunities and jobs for other black women, along with using her fame and financial success for philanthropy and advocacy. A $1,000 gift to establish an African-American YMCA, on Senate Avenue, garnered national publicity and awe. Walker went on to help fund a national anti-lynching initiative and other race-related causes and was appointed by Indiana’s governor to a national education task force. She was determined to use her influence to benefit others.

Walker helped fund a national anti-lynching initiative and was appointed by Indiana’s governor to a national education task force.

In some ways, Walker was modest—she did her own laundry rather than pay someone to do it—but also relished her fortune. She dressed in rich fabrics, expertly tailored, and purchased multiple cars. She hired a full-time chauffeur, but one of her greatest pleasures in life was the freedom afforded by driving an automobile; whether in the city or cross-country, there would be no “separate train” for Walker. She careened through Indy in her small “Waverly electric” for quick shopping trips or to an afternoon matinee at the Isis Theatre on Illinois and Market streets. She was also one of the first to purchase a limited-edition, seven-passenger Cole touring car.

One image from the Indiana Historical Society shows Walker in her Model T Ford, alongside her niece, factory forelady, and bookkeeper. What fun it must have been to sputter through the streets with the entrepreneur, dreaming of the day all black women would have such opportunities.

Tiffany Benedict Browne runs historicindianapolis.com, which she hopes will become as lucrative as Walker’s business.