November’s Transit Referendum: A Lot on the Line

Nikki Hart commutes two hours to work every day. First, the IndyGo rider takes her son to daycare, then waits 30 minutes for another bus to carry her to a different route, where she finally can board a bus that takes her to her job at RecycleForce on the east side. Before she moved to an area with more frequent service, that two-hour commute stretched out to almost three. For Hart, scheduling her life around the bus is a necessary inconvenience. She sacrificed her car when she escaped an abusive relationship in Anderson and moved to Indianapolis. Still, she desperately wishes Indy had a faster transit system so she and her son could have more of the day at home. “We’re spending way too much time on the bus,” she says.

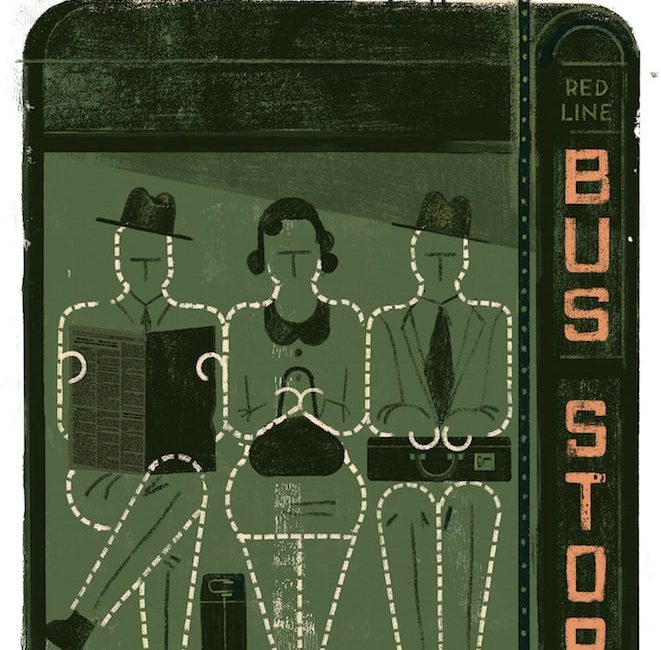

Hart might get her wish soon. Plans to expand Indy’s transit options have been stuck in neutral for years, but they’re finally moving forward. The Red Line, the city’s first bus rapid transit (BRT) route, should be up and running by 2018. It promises electric buses in dedicated lanes, arriving every 10 to 15 minutes, seven days a week. Most of the funding for construction of the stations and operation of the buses already is in the works. This month’s referendum doesn’t determine the fate of the Broad Ripple–to–University of Indianapolis circuit the Red Line will travel, but establishes the foundation for all of the spokes that might follow—the Purple Line, the Blue Line, and faster traditional bus service on many routes. Voters will decide whether to raise their own income taxes 0.25 percent to fund those improvements this month.

The system would be fully built out by 2021 if approved. But a grassroots group in Meridian-Kessler hasn’t let the Red Line’s inevitability dampen their enthusiasm for fighting the expansion. At informational meetings intended to be public-transit cheerleading sessions, they have been standing up to protest. Introducing BRT routes all over Marion County, these opponents say, will snarl traffic, cost hundreds of millions of dollars, and decrease property values. More importantly, they believe it won’t do a thing to attract more riders in a city hooked on cars.

Some of those claims may be dubious, but critics are right to question our collective will to leave our cars in the garage. Whether the referendum passes or not, the future of public transportation here relies on a radical change in culture. Sustaining a system of BRT routes would require attracting people who choose to ride the bus, not just those who need to, like Hart. And opponents say that will never happen.

Like a rider at an IndyGo stop, Indianapolis has been waiting a long time for the Red Line. The push for better transit options started gaining traction here in the early 2000s, but a formal proposal—the Marion County Transit Plan—didn’t take shape until 2009. Since then, the organizations behind it, such as IndyGo and Indy Connect, have hosted about 700 public meetings and sorted through more than 10,000 comments. The ball really started rolling in 2013, when the Chamber of Commerce took the lead to secure dedicated funding. When advocates finally succeeded in convincing politicians to put the issue before the voters this year, they already had some money in the works for the first phase.

According to Bryan Luellen, IndyGo’s director of public affairs, the Marion County Transit Plan won’t change IndyGo’s overall footprint much, but it will “shore up” existing service. Only two of the city’s 31 routes currently offer service every 15 minutes; the rest run every 30 or 60 minutes. And some routes don’t run at all on the weekends. “We haven’t funded a system at a high enough level where people can walk out to a bus that’s coming soon and that’s coming seven days a week,” Luellen says.

To proponents, BRT was the obvious solution. IndyGo chose to start with the Broad Ripple–to–University of Indianapolis stretch because it offers the most return on investment. The Red Line corridor is densely populated by people and businesses, and portions of it (College Avenue through SoBro, Capitol Avenue through downtown) are very walkable. That path also encompasses some of the city’s most popular routes. About 6,000 riders get on the bus in that area each day, and IndyGo estimates that an additional 5,000 people could start riding because of the improved service.

Of course, expanding the BRT system throughout the city would mean spending more money. Among metropolitan areas in the U.S., Indy currently ranks 33rd in size but 86th in transit funding per capita. If voters approve the tax increase and the City-County Council follows suit, the city would jump to 65th, and it would have a dedicated source of funding for transit for the first time. (IndyGo receives some property tax dollars from the City-County Council, but the amount is never guaranteed.) The Red Line alone will cost $96 million to build, and the rest of the system would eventually run $300 million more. Which sounds exorbitant, until you consider that installing a light rail system (a common alternative to BRT) would cost billions. Funding for the first phase appears to be in place. As of press time, IndyGo expects Congress to approve a $75 million federal transportation grant for the Red Line, and the rest of the $96 million has been secured from local sources.

Even if the referendum passes to fund the other BRT lines, though, IndyGo needs to attract a new group of commuters to support a system of those routes. More riders will fit in the bigger, electric buses, and the organization hopes revenue from fares will help cover increased operating costs. Proponents point to shifting lifestyle trends to show the potential for new riders. According to a University of Michigan study, the number of cars per person in this country peaked in the early-to-mid-2000s and has dropped ever since. The study cites increases in telecommuting and use of public transportation as potential factors. IndyGo also conducted focus groups that suggested more local residents would use buses instead of cars if transit options were reliable. IndyGo’s Luellen gave up his own car last year, and he’s confident many others would do the same if BRT ran throughout the city. “Frequency and hours of service,” he says. “Those are the biggest drivers for ridership.”

At a Red Line informational meeting at the Tube Factory this past July, IndyGo director of special transit projects Justin Stuehrenberg made it halfway through the Q&A portion of the event before a familiar adversary rose for yet another tense exchange with him. Robert Evans represents a group called Stop the Red Line, which started as an objection to that route, but has since spent much of its time fighting expansion of the system. Evans began asking pointed questions about the language in one of IndyGo’s recent federal grant applications—anything that might bring into question the project’s legitimacy. Had it really stated that Butler University was within a half-mile of College Avenue? Stuehrenberg answered as politely as he could, and his counterpart eventually walked out.

Evans joined the protest movement because he fears the costs of the project have been underreported and that taxpayers will end up paying more than they expect. For example, operating the full Marion County Transit Plan system would cost about $108 million a year, which is $38 million more than IndyGo’s current budget. Most of that would come straight from taxes, either those outlined in the referendum or existing property taxes.

Money isn’t his only concern, though. Evans lives near the Red Line’s College Avenue section and believes it will destroy the intimacy of SoBro, making it very difficult to park and drive in the neighborhood. Like others in the group, he opposes the infrastructure of the plan, and doesn’t want to see the changes coming to his neighborhood spreading. Because the BRT buses will have a dedicated lane in some areas and bus stops will be on elevated medians, opponents say they will cause more congestion in already busy streets. College Avenue between 66th and 38th streets, for example, will be down to one lane in each direction. Some residents won’t be able to make left turns into their driveways, and many businesses will lose parking. The buses also will have dedicated lanes on Meridian Street between 38th and 18th streets and on Capitol Avenue between 18th and Maryland streets, so those stretches will lose lanes for cars, too.

Lee Lange, another Stop the Red Line member, thinks it’s going to be a lot harder to drive in neighborhoods across the city, and if this system doesn’t work, it will be difficult to get rid of the elevated medians. “It really doesn’t make any sense,” she says. “We just think there’s a better solution that does not involve permanent lanes.”

Lange and Evans also are not convinced that the BRT lines will be as effective as proponents promise. In order to operate faster, IndyGo is cutting some stops along the Red Line corridor, which will mean a longer walk for some who want to catch the bus. It’s hard to imagine professionals in suits walking a mile in the rain for transportation. They also question why IndyGo isn’t debuting BRT in neighborhoods where more people rely on public transit. Hart, the mother with the two-hour commute, won’t benefit from the Red Line at all; she will have to wait to see if voters agree to fund the proposed Blue Line. Lange says IndyGo should have started with more buses in areas that have been identified as running slow or with populations that need a ride. “We are supportive of good, efficient mass transit,” Lange says. “Buy more buses, hire more drivers, and run those routes with the frequency you need.”

Both sides agree the referendum will drastically impact the future of Indianapolis. If it passes, though, it also could spur BRT routes in suburban counties. So far, those areas have been taking a wait-and-see approach. More than 60,000 people commute from Hamilton County to Marion County every day. Not only could more transit options cut down on rush-hour traffic between them, they also could help people move around Carmel, Fishers, and Noblesville, where there essentially is no bus service. Doug Callahan, trustee of Clay Township in Carmel, says he and his staff have had to personally drive residents in need to other areas of the county and to Indianapolis. The ever-increasing traffic also is a concern. “If we don’t start our transit system soon, we are really going to have an issue,” he says. “What do we do, keep building lanes in these highways? Let’s start thinking about other options here.”

The ultimate goal is to expand the Red Line into Hamilton and Johnson counties, but they would have to help foot the bill. Both counties had an opportunity to put a referendum similar to Marion County’s on the ballot this year, but governing bodies in each place decided against it. The Clay Township board didn’t even vote on putting a referendum on the ballot because board members thought residents needed more information. Though Callahan says he supports transit, he thinks his board made the right decision to pass this time and revisit it in 2018. If the Red Line looks like a success two years from now, that would make selling the idea much easier.

Evans says his group is gaining supporters, however, and he hopes they can not only persuade voters to reject the Marion County referendum, but put enough pressure on transit groups to reconsider the Red Line as well. While that remains a long shot, he thinks a resounding “no” vote would send a message to IndyGo.

But Mark Fisher, an IndyGo board member who has been pushing for better transit here for more than a decade, believes the momentum belongs to his side. Last year, he played a key role in getting the Indiana General Assembly to grant local governments the authority to add referendums like the one in Marion County to ballots. Any time labor, environmental, and social justice groups work together like they are on this project, he says, “you’ve got a winner.” The referendum is far from a slam dunk. It not only needs to pass, it must do so decisively so City-County Council members will feel comfortable enacting the tax. But no one wants the Red Line to be remembered as a road to nowhere. “If we don’t do this right in Marion County,” Fisher says, “the likelihood of a truly regional build-out will be greatly diminished.”