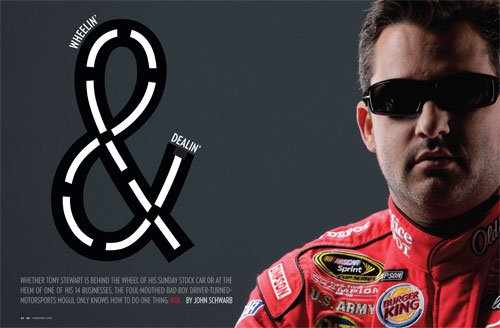

Tony Stewart Is Wheeling and Dealing

Editor’s Note: This article originally ran in the February 2010 issue.

The air is dirty. Which is to say, it’s perfect. Eldora Speedway nights are like this, with angular, aging racecars kicking up just enough clay and haze to send every one of the 20,000 spectators home with a dirt epidermis. These vehicles are made for the task, with light bodies, an enormous swooping wing, and hulking rear tires built to propel drivers through the “cushion,” that sweet spot at the top of the racetrack where speed lives. Dirt pros and dream-filled amateurs have converged here, amidst the corn and soybean fields outside the hamlet of Rossburg, Ohio—past a sign directing travelers to Annie Oakley’s gravesite, past another for the Kitchen-Aid plant where standing mixers are made—for more than a half-century, trying to solve the “Big E.” There is no other place quite like it.

A different crowd is here tonight. The cars are showroom-spiffy, decaled and numbered as if this were a Sunday NASCAR race. The lively fans have filled the oval to capacity and then some. And the big-time drivers milling around, stranded an hour away from their sleek private planes parked at the Dayton airport, are linked not only by their shining careers but by their undeniable right to hold a grudge against their host: In 2000, he bloodied the lower lip of Robby Gordon ($30 million in race winnings to date) after on-track conflict turned into off-track shoving; he once ran Matt Kenseth (18 wins, $66 million in prize money) into the grass at Daytona, after they had bumped around all afternoon; he has even been threatened with a one-way trip into the wall by Jeff Gordon, one of the coolest, calmest, and most successful drivers of all time. Yes, this is an unlikely party.

But there he is—a two-time Sprint Cup champion, longtime NASCAR bad boy, and up-and-coming mogul—glad-handing and smiling for the pay-per-view cameras, beloved everywhere he turns. When Tony Stewart asked, these drivers took a midweek night in the middle of their racing season to travel to the middle of nowhere and whir around a half-mile spit of dirt, all to raise money for a charity hand-picked by him. They came not because of who Tony Stewart was, but because of what he has become. Today, at 38, he is one of the most powerful figures in a motorsports league that each week draws more live spectators than any Super Bowl ever has. No longer just a loud mouth who drives in circles, Stewart has become some kind of scruffy CEO, a mogul commanding a growing empire of 14 businesses, from racing teams and small tracks to a company that sells Tony Stewart Original Beef Jerky.

But if this upstart-turned-businessman from Columbus, Indiana, is now the NASCAR personality with the Midas touch, he isn’t sharing any of it on this night at Eldora Speedway. He glides his No. 14 car around the cushion almost as if on skates rather than racing treads, gunning for the front.

This month, NASCAR returns to Daytona to kick off its 52nd season, the league’s economic muscle, popularity, and longevity one of the most unlikely success stories in all of sports. It took root during Prohibition, when moonshiners souped up their own vehicles in order to outrun the revenuers. When alcohol became legal again, the cars with a little something extra under their hoods began taking on each other at dirt tracks, and by 1948 the National Association of Stock Car Auto Racing had been born. In 1979 at Daytona, in the final stretch of the first nationally televised 500-mile race, the two front-runners wrecked, and then finished their fight with fists while the distant third-place car took the checkered flag. In that moment, ripe with roaring engines, raw emotion, and gritty personalities, blue-collar America—all of it, not just the Southeast—found its true sports love.

Today, cars with impeccable paint jobs and decals—two identical vehicles, in case the original perfect car ends up in a wreck—arrive at races in gleaming haulers, manned by crewmen in monogrammed uniforms. It costs somewhere between $20 million and $30 million to run one car through the 36-race NASCAR season in pursuit of the Sprint Cup, the top prize in the field. Unlike other professional sports such as football and basketball, in which team owners share television revenue and other income, NASCAR teams are independent contractors; they must find their food, bag it, and bring it home. The cars don’t run on gas, goes an old NASCAR cliche—they run on money.

Primarily that money flows from sponsors, who link their brands to their drivers and hope for wins, recognition, and nothing like a Tiger Woods-scale scandal. These arrangements make the rollicking heights of Tony Stewart’s trajectory all the more unlikely—both over the course of his $85 million NASCAR career, and even now, as it is entering a new phase entirely. A champion in virtually everything he has driven, from go-karts to midgets to Indy cars to stock cars, Stewart has always been mouthy (most of the public comments for which he is best known cannot be printed here), a throwback to days when stock cars were driven by men with a penchant for breaking rules. Fortunately for him, Home Depot stuck with him for a decade, even when his outbursts turned outlandish.

As he progressed, Stewart grew more confident and resourceful.

Then last year, Tony Stewart did what most racecar drivers would consider unthinkable: He turned away from a doting sponsor, a respected team, and a revered boss—to find his own sponsors, build a new team and become his own master. In a sense, he has given in to the sports-marketing mantra of the age: He has become his own brand. Over the past decade, Stewart has slapped that brand on everything from barbecue sauce to beef jerky to remote control cars. But with Stewart-Haas Racing, the driver they call “Smoke” has seen unprecedented success on the world’s largest racing stage. And he did it by doing what he’s always done: He just wins.

As a young man racing on small tracks and trying to make enough money to maintain a competitive car, Stewart would set up shop in the infield after races, selling Tony Stewart T-shirts out of his Mazda RX-7. “You took a hanger, put it on the roll cage of the race car, and sold shirts out of boxes in the trunk,” Stewart says. “We stayed until everybody left, or until they threw everybody out.”

Born in Columbus in 1971, Stewart had a love of anything with wheels, first wearing out the plastic rear “tires” on his Big Wheel and figuring out a way to lean into the turns, popping the inside rear wheel into the air, for laps at a time around his father’s garage workshop. Nelson Stewart, a traveling salesman, was a local track racer and fan, taking the family to Salem Speedway and Winchester Speedway like other Hoosier families dutifully take their kids to see the Brown County foliage or downtown Indy museums. When Nelson bought Tony a go-kart, the five-year-old wore out a path in the yard. At seven he was taken to a small dirt oval for his first organized-racing laps, and the next summer he was a regular there. In 1980 he was a class champion at the Columbus fairgrounds.

As he progressed, Stewart grew more confident and resourceful. During a trip to Iowa for a major kart race in 1983, Nelson lectured his son on how tough the competition would be, how he’d be going up against teams with far better equipment than what the family was able to pull together in Columbus. (The family mortgaged the house so Tony could move up the ranks; Tony blamed his racing for the strain that led to his parents’ divorce while he was in high school.) The 12-year-old let the father talk and sat quietly for some 20 minutes before looking him in the eye and promising he would win. And he did.

He was also developing as a leader. His mother, Pam Boas, who now heads the Tony Stewart Foundation, recalls her son attending a lock-in at Asbury United Methodist Church. “He was in the youth group, and they had taken pizza orders for Super Bowl Sunday. They had this lock-in so they could put them together,” Boas says. “Tony had everybody in an assembly line, told them this was the most efficient way to get it done so they could go do whatever they wanted to do. However, Tony didn’t help; he just had them all lined up.”

When Stewart was 18, he bounced around central Indiana, living with various racecar owners and trying to jump-start a big-time racing career while working odd jobs, including at a McDonald’s drive-thru. His NAPA delivery truck route traveled Georgetown Road, right past the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. With all the jobs he made just one demand—time off for races. And along the way, he picked up his nickname, Smoke, for the hard-charging way he attacked the turns when he first switched from dirt to pavement.

The moonlighting racer won all over the Midwest in sprint cars, drawing the eye of Indy Racing League representatives, who helped him land a seat with John Menard, the home-improvement store magnate and owner of an IndyCar team. He raced in the 500 on May 26, 1996, the first of five appearances, and won an Indy Racing League championship in 1997. In a different era, Stewart might have made a career out of open-wheel racing. But that’s when NASCAR came calling.

It was a football coach on the line. Joe Gibbs, a three-time Super Bowl winner with the Washington Redskins turned racing magnate, had always had an eye for talent. In 1999, he also saw that the wave of the future in NASCAR was with multi-car operations. He started a new team to race alongside veteran Bobby Labonte, and offered the driver’s seat of the No. 20 Home Depot Pontiac to the open-wheel star.

Gibbs was a hands-on owner as far as being around the shop and wearing a headset on race weekends, and on more than one occasion he implored his star young driver to cool off. But he kept his distance from the teams as they worked. “I learned a lot about how to organize people,” Stewart says today. “I can promise you, Joe doesn’t know anything about those racecars. He doesn’t know how they work, but he knows how to hire the right people to do the right jobs in the organization, and that’s what has made him successful. Part of that process is being able to take five résumés that can be identical and being able to pick which guy is going to work with everybody else and has the right mindset, no matter whether there’s eight more guys that have the same skills they have.”

While Stewart was busy winning rookie of the year honors in 1999, he was also sowing the seeds of his own empire. Late that year he started Tony Stewart Racing, a sprint/midget car team for young drivers needing a break and older drivers needing a home. Companies such as Bass Pro Shops, Armor All, and Indiana’s own J.D. Byrider—a used car and financing company—all sponsored his team’s cars, getting a piece of Stewart’s aura even when they weren’t getting Stewart behind the wheel. In 2003, after winning his first Sprint Cup the previous year, Stewart bought out a remote control race car manufacturer, Custom Works R/C Cars, which has won 90 percent of the national championships in remote-control racing since 1988.

Owning racecar teams big and small was satisfying, but nothing compared to the purchase he made in 2005—the same year he grabbed his second NASCAR Championship. Noting that “(NASCAR) is my profession, but Eldora is my passion,” Stewart bought his Ohio racetrack and later became part owner of Paducah International Raceway in Kentucky and Macon Speedway in Georgia. Eldora remains “a place that he holds sacred, a place that exemplifies the aura and the tradition of grassroots racing that Tony has an affinity for preserving well into the future,” says Brett Frood, Stewart-Haas executive vice president and chief operating officer for Tony Stewart Racing. “He loves being there. Loves being there when he has off weekends. He flew back and forth three times last year. I see Tony owning it forever.”

Perhaps the most surprising component of his empire is True Speed Communications, a public relations company that has become one of the most respected in the racing industry—a seemingly wise investment given the boss’s long record of blow-ups and PR mishap.

Stewart passed Dale Earnhardt Jr. in merchandise sales—a remarkable feat considering Earnhardt’s legacy and loyal spectators.

Joking aside, the employees across all parts of Stewart’s business kingdom can appreciate his success in very serious terms. During the economic turmoil of 2009, nearly every facet of motorsports was hit hard. Some 1,000 crewmen for various NASCAR teams lost their jobs in North Carolina, the epicenter of stock-car racing. Press boxes became less crowded. The public relations armies thinned. But no one from Tony Stewart’s 200-person workforce, across all the businesses, lost a job. He says he is still getting used to what it means to have that many people behind him, depending on him, but he’s starting to take as much satisfaction in taking care of those people and their families as in winning 500-mile races. “We get so focused on winning. What you don’t realize until you get to the top of the hill is that there’s other hills out there, there’s other things in your life,” he says. “Until then you have tunnel vision. What you do, what you say, you don’t realize the weight behind you.”

Also last year, in what may be the single most immediate measure of success in NASCAR fandom, Stewart passed Dale Earnhardt Jr. in merchandise sales—a remarkable feat considering Earnhardt’s legacy and loyal spectators. Stewart shrugs off the achievement, noting that his followers restocked their closets in 2009 because of his new team, car number, and racing colors.

Yet maybe his is a brand for the age—imperfect, but never dishonest. Sponsors who once cringed at the next episode from their driver now want the man to be himself. Office Depot representatives love him because he’s fighting for his small business; Old Spice loves the manly-man swagger, everyday-Joe appeal. Even Stewart likes himself more. “I liked the guy that came into racing, not the guy I became,” Stewart says. “It’s been a process of learning how to be a celebrity, how to be popular, how to be not popular, and how to adjust your life to it. I wasn’t losing sight of who I was; I was fighting to stay who I was.”

Certainly, whoever he is or is becoming, he is a winner. Last year, after riding atop the standings for much of the season, Stewart had a bumpy Chase for the Sprint Cup and finished 6th in the standings and his teammate Ryan Newman came in 9th—a success for a first-year driver-owner by any standards. This month he’ll look to build on that success, starting at Daytona, where the Great American Race still stands as one of the few jewels absent from the Stewart racing crown. But if the past is any indicator, it won’t take long for Smoke to pull to the front, just like he did at Eldora, where on Lap 13, he guided the No. 14 car into the lead—and never relinquished it.