‘At Home with Ernie Pyle’: An Excerpt

Ernie Pyle earned fame as a nationally syndicated columnist and overseas World War II correspondent, of course. But he never really left his roots behind—nor did his writing, in which Pyle’s small hometown of Dana, in western Indiana, and the family, friends, and neighbors who lived there, appeared throughout the journalist’s career.

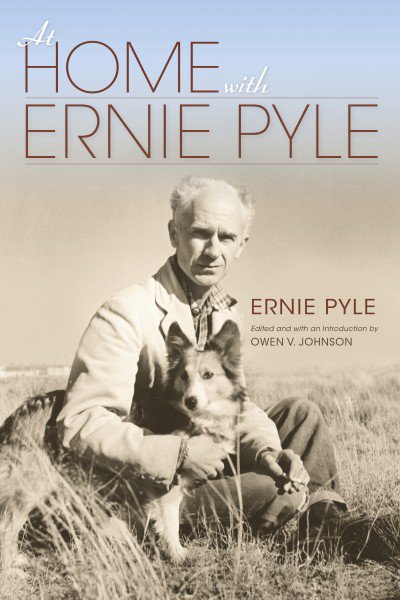

Compiling his writings about the state for the first time, At Home with Ernie Pyle, a new volume published by Indiana University Press, reveals just how important those Hoosier ties were to Pyle, not only as a fertile source of subjects to write about, but as a kind of spiritual underpinning to his well-grounded, everyman appeal.

“Dana and its inhabitants were the inspiration for a number of Pyle’s columns,” says Owen V. Johnson, an associate professor emeritus of IU Journalism who edited the new book. “Those stories resonated with readers across the country who shared a sense of the importance of community.”

In the following columns excerpted from the book, Pyle, with touching candor and haunting prose, both struggles with the mortality of his beloved mother, Maria, and finds solace in the simple kindness of the Indiana neighbors who rallied around her when she needed them most.

“Pyle was an only child, something unusual in rural Indiana at the beginning of the 20th century, so his relationship with his parents was much more intense than was common with his friends,” says Johnson. “With her death, Pyle realized just how well she had prepared him for life, even if she didn’t understand very well life outside of western Indiana … He realizes just how much her absence will change his life, even though, like her dog Snooks, he can’t comprehend all of it.”

March 16, 1937

Dana, Ind.—In the last few years we’ve heard a lot about the “good neighbor” policy as a theory for nations.

But to me, and I suspect to most of us, “good neighbor” has become a mere academic term. We who live in cities have almost forgotten what a good neighbor is. But the country people know. It’s the same thing it was 30 years ago, and maybe a hundred years ago. Let me tell you:

My mother was stricken with paralysis on a Thursday night. By Friday morning the whole countryside knew about it. I am sure at least a thousand people, in town and on farms for miles around, had got the news. Word travels fast among the neighbors of western Indiana.

The help began to roll in instantly. The strongest men in the neighborhood came, without being asked, to help lift my mother in her bed. The women came, to help my Aunt Mary with the washing and housework. Others came, and others called, to see what they could do.

Mrs. Goforth baked two butterscotch pies and sent them over. Lou Webster sent up an angel-food cake, and she came twice to help us with the work. Hattie Brown cooked a roast, with dressing and everything, and sent it up steaming hot for our Sunday dinner.

Cousin Jediah Frist, who will be 80 his next birthday, drove down from town in a sleetstorm to see if he could do anything. Nellie Potts brought flowers clear down from Newport. She is Lou Webster’s sister.

Mrs. Bird Malone brought a beautiful hyacinth. When my mother had her first stroke a year ago, Bird and Mrs. Malone started over to see her. On the way, the car door came open and Mrs. Malone fell out and broke her arm, at the shoulder. She was in a cast for three months. She still can’t close her hand. I told her she was pretty brave to start the same trip over again this time.

Oll Potter’s mother sent a whole basketful of fresh sausage, and pork tenderloin, and a peck of apples. When I was a little boy, the Potters were the poorest people in all our neighborhood. They were just up from the Kentucky hills, and we thought they talked funny, and never smiled. Dan Potter worked out by the day for farmers.

But the Potters toiled, and saved their money, and all their boys grew up to be workers. Now they live in a nice house and have a fleet of cattle trucks, and the whole country admires them for the way they’ve raised themselves by the boot-straps. It was Mrs. Potter who sent the whole basketful of stuff.

Mrs. Frank Davis, the new neighbor, just up the road, brought over freshly butchered pork ribs. My Aunt Mary said it was good of her, she not knowing us very well. Mrs. Davis said that once when she was sick over in Parke County people were mighty good to her, and she told them she didn’t know how she could ever repay them, but they told her she didn’t need to repay them personally, just so she did good things for other folks when they needed it. And that’s what she was doing.

My Uncle Oat Saxton brought over a freshly butchered side of a hog. My Uncle Oat keeps batch, and he is the laughingest man in Vermillion County. He laughs at everything, and especially himself, and when he laughs it is like the clear melodious peal of a cathedral bell. It helped ease the strain to have him come and sit in our kitchen, and take off the lid and spit in the stove, and tell stories and laugh at them.

On Sunday there were 38 people at our house. We couldn’t let them in the front room, and at one time the kitchen and dining room were so full half of them had to stand up.

Anna Kerns was one of the 38, and when she left she didn’t say, “Now if there’s anything I can do …” she said, “Mary, I’ll be here at 7:30 in the morning to do the washing for you.” And she was too, and stayed all day, and got down on her knees and oiled the linoleum, and then sat all afternoon with Mother while we rested.

Bertha and Iva Jordan came twice for half a day each. They brought two pies the first time and a cake the second time, and they did the washing and ironing. Iva Jordan was my first school teacher. She is gray-haired now, but she is still pleasant and soft-spoken, as she always was. She wore an apron and a dust cap while she did the ironing in our kitchen. We talked about my first year in school, and we both hated to realize it was more than 30 years ago. Jennie Hooker came and stayed all day. She is the mother of my closest childhood chum [Thad Hooker]. Bill and Beatrice Bales came and sat up all night, and ran innumerable errands for us in their car. Rema Myers, the doctor’s wife, came one afternoon and did the ironing. When we were high-school age, Rema and I never dared to go anywhere together, we always got the giggles so bad. Rema still gets ’em. She is the prettiest girl in our town.

Uncle John Taylor (he is Mother’s brother) came and sat up two nights, and would have stayed every night if we had let him. Claude Lockeridge got out his truck and drove nearly 20 miles on a snowy day to get a hospital bed from Earl White’s, north of town. Other people did things, and brought things, and called up, but I can’t remember them all now.

For 40 years my Mother was the one who went to all these people when they needed help. They haven’t forgotten, and now they’re coming to her in droves. Indiana farmers know what a “good neighbor” policy is. It’s born in them.

April 10, 1941

Dana, Ind.—My father met me at the train in Indianapolis. When we shook hands there were no tears in his eyes, and I was glad.

When we drove up the lane to the farmhouse my Aunt Mary came rushing out onto the front porch. And she did not cry. And I was glad.

And then the dog Snooks came running up, but she was timid and afraid as though she could not make up her mind. There seemed no life in her, and she was sad and lost.

The little dog Snooks was the only one who let on, and her loneliness cut me as deeply as though she had shed tears. For Snooks spoke in her wordless aimlessness the void that my mother left behind her when she went away.

One drear evening in London just at dusk, when outlines become soft and begin their slow blending with the final blackness of night, a friend and I started out to dinner.

We were walking down the Strand, brushing past the late pedestrians hurrying for home before blackout and bombers could catch them.

We had gone about two blocks when we heard hurrying footsteps behind us. We turned, and saw that it was a little bellboy from my hotel.

The lad’s name was Tom Donovan, and he was the one who had showed me my room on that first strange night months before when I arrived in war-torn London.

I had always been fond of him, for his face was so bright and eager, and his manner so nice, and all his little actions so thoughtful.

“This telegram just came for you sir,” he said. “I thought maybe I could catch you.” I thanked him and he started on back.

There was barely light enough to see. I stepped over to the curb, out of people’s way, while I tore open the telegram and read it.

“What is it?” my friend asked. “More good news from home?”

“Read it,” I said, and went on ahead. When he caught up he said “I’m sorry,” and we walked on toward Leicester Square as though nothing had happened. The London night grew quickly darker around us, and we spoke no more as we walked.

It was the cablegram that told me that my mother, far away in Indiana, had come to the end of her life.

That night in London, back in my room alone, it seemed to me that living is futile, and death the final indignity. People live and suffer and grow bent with yearning and bowed with disappointment, and then they die. And what is it all for? I do not know.

I turned off the lights and pulled the blackout curtains and went to bed. Little pictures of my mother raced across the darkness before my eyes.

Pictures of nearly a lifetime. Pictures of her at neighborhood square dances long, long ago when she was young and I was a child. Pictures of her playing the violin. Pictures of her doctoring sick horses; of her carrying newborn lambs into the house on raw spring days.

I could see her that far day in the past when she drove our first auto—all decorated and bespangled—in the Fourth of July parade. She was dressed up in frills and she won first prize in the parade and was awfully proud.

And one midafternoon when I was 9—the first day I ever drove a team in the fields all by myself. She made many trips to the field that day, to bring me bread with butter and sugar spread on it—and to make sure I hadn’t been run over by the harrow. I could see her, there in the London darkness, as she came out toward that Indiana field more than 30 years ago.

The sirens sounded and the groan-groan-groan of the engines came, and the far guns began to roll off their symphony like the sad distant thunder on a hot prairie night.

I could see her on bitter winter days in the old familiar woolen hood, with her nose red from cold, and wearing a man’s ragged coat fastened with horse-blanket pin.

I could see her as she stood on the front porch, crying bravely, on that morning in 1918 when I, being youthful, said a tearless goodby and climbed lightly into the neighbor’s waiting buggy that was to take me out of her life.

Pictures of a lifetime. Pictures of her in worry and distress, pictures of her in anger at fools or injustice, pictures of her in gaiety, pictures of her in pain. They were all as clear and vivid as if I were there again on the prairies where I was born.

The pictures grew older. Gradually she became stooped, and toil-worn, and finally white and wracked with age … but always spirited, always sharp.

I wondered if she could hear the guns now wherever she was, and what they meant to her if she could …

On the afternoon that I was leaving London, I called little Tom Donovan, the bellboy, to my room. My bags were all packed. One by one the floor servants had come in, and I had given the farewell tips.

But because I liked him, and more than anything else, I suppose, because he had shared with me the message of finality, I wanted to do something more for Tom than for the others. And so, in the gentlest way I could, I started to give him a pound note.

But a look of distress came into his face, and he blurted out, “Oh no Mr. Pyle, I couldn’t.” And then he stood there so straight in his little English uniform and suddenly tears came in his eyes, and they rolled down his cheeks and made him choked and speechless, and then he turned and ran through the door. I never saw him again.

On that first night, I had felt in a sort of detached bitterness that because my mother’s life was hard, it was also empty. But how wrong I was.

For you need only have seen little Tom Donovan in faraway London wretched at her passing, or the loneliness of Snooks after she had gone, or the great truckloads of flowers they say came from all over the continent, or the scores of Indiana youngsters who journeyed to her both in life and in death because they loved her, to know that she had given a full life. And received one, in return.

For for more coverage of Indiana’s Bicentennial, go to IndianapolisMonthly.com/bicentennial.

Excerpt and book-cover image used with permission of Indiana University Press.