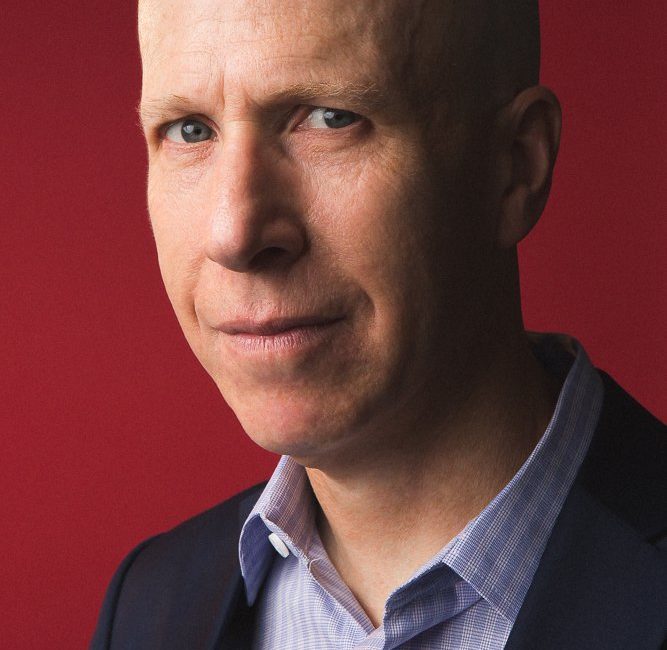

Q&A: Jonathan Eig, Ali Biographer

The New York Times bestselling author published the first comprehensive biography of Muhammad Ali (Ali: A Life) October 1 and has appeared on The Daily Show with Jon Stewart. Ahead of his November 1 appearance at the Ann Katz Festival of Books & Arts, we parsed fact from fiction about the boxing legend.

How has writing the book changed your opinion of Ali?

He’s a lot more complicated than the guy whose poster hung on the wall of my room as a kid. I have mixed feelings about him, because some of the things he did were awful and inexcusable. But I came away still admiring him. He never really got a big ego—for all of his bragging, he somehow managed to always treat people as if they were equals.

What was the most unexpected thing you unearthed about him?

I was surprised at just what a sucker he could be. He would give away all his money; he would let people take advantage of him, and he just never really cared. If somebody wanted to take a million dollars of Ali’s money, Ali really didn’t raise a hand to stop him. He just wanted everybody to be happy.

What are some myths about him that aren’t true?

When he came back from the Olympics in 1960 with his gold medal, he was supposedly so upset about not being served in a restaurant because he was black that he threw it in the Ohio River. I’m pretty certain that never happened; it was just a story that his ghostwriter made up at one point in the ’70s. And people have the impression that he was a boxing genius and that he used these tricks like the rope-a-dope to fool his opponents. He was a boxing genius, but the rope-a-dope was a terrible strategy that really only worked in one fight. He gets too much credit for that one.

Is it true that he never denied an autograph request?

That’s pretty true. In fact, if somebody was picking him up in a building alley, he’d say, “Go around to the front so more people will see me.” And then he’d take an hour or two to sign autographs before getting into the car. He needed constant attention—he was almost childlike in that way.

For someone who constantly boasted “I am the greatest,” what was his biggest insecurity?

He was terribly worried about being alone. Maybe it came from having an abusive father who was a heavy drinker and occasionally physically assaulted him, but I think Ali just felt like he had to please everybody. He wanted people to always be happy around him.

You’ve rounded up an extensive collection of Ali memorabilia, including Ali cologne and bedsheets. How did that start?

I’d never collected stuff before, but once I started researching this book, I started coming across these things. Sometimes I would interview people who had stuff, and they would say, “Well, if you want it …” So now I have paintings that Ali’s brother did of Ali, a letter Ali wrote to his manager, a pair of Ali boxing gloves—just stuff that I found along the way that I thought was really cool.

Anything really special or unique?

The one thing I’m most proud of, and that I think is most important, is a letter Ali wrote. His wife was mad at him—he was cheating on her, and she thought he’d forgotten why he became a Muslim and was acting like he was bigger than God. So she said, “I want you to sit down and write why you became a Muslim.” And she handed him a paper and pen and he started writing.

When I was at his wife’s house, she showed me this letter, and when I said I thought it belonged in a museum, she asked me if I wanted it. I said I would take it, but I promised that I would never sell it and that I would donate it to a museum after I was done with my book. And now it’s going to the Smithsonian Museum of African American History.

Some sources wanted you to pay for interviews while you were working on this book. Is that common?

It happened a lot for this book, and I think it’s just because people in boxing are cutthroat. They ask the question, “Well, you’re getting paid to write this book; why shouldn’t I get some of it for helping you?” But I told them that I didn’t consider it ethical for a journalist to pay for sources. They didn’t really care about my ethics, but I held out; although I gave Ali’s brother some money for a painting that he did.

Did you get to meet Ali?

Yeah, I did—really briefly. I tried to meet him several times, and the first few tries, he was not feeling well and I didn’t get to see him. But then finally I went to an awards ceremony in 2015 where he was being honored, and I got to talk to him a little bit. I told him I was working on a book, and that it was a great privilege and I was working really hard to try to get it right. I asked him if there was anything he wanted to say, but he didn’t answer. He wasn’t really speaking that night. So I didn’t get anything out of him, but at least I got to look him in the eye and tell him that I was working on this book, and that meant a lot to me.

You’ve written a lot of historical biographies—have you ever thought about tackling someone contemporary?

I wouldn’t really want to, because I think you need time to see why someone’s important. Even with giant figures like Michael Jordan or Derek Jeter, I don’t think enough time has gone by to really place them in history. If something came along and I couldn’t resist, though, maybe I’d make an exception.

Such as?

Oh, man, I don’t know—if LeBron called me, I’d talk to him about it, or Serena, or Barack Obama. I would take the phone call, certainly.

What’s your next project?

I’m working on an Ali documentary with Ken Burns for PBS, which is keeping me pretty busy. And I’m hoping to get started on my next book soon, but I’m keeping it under my hat for now.

Eig will speak about his latest book, Ali: A Life, at the Ann Katz Festival of Books & Arts at the Arthur M. Glick Jewish Community Center (6701 Hoover Rd.) on Wednesday, Nov. 1, at 7 p.m. Tickets are $10.