The Story of Us

A reader averse to political correctness might dismiss Hoosiers: A New History of Indiana as yet another example of liberal academic revisionism. But author James H. Madison would no doubt argue that he is simply setting the record straight. And not just any record, but the record that Madison—the Thomas and Kathryn Miller Professor of History Emeritus at Indiana University—has spent a long and distinguished career helping to compile.

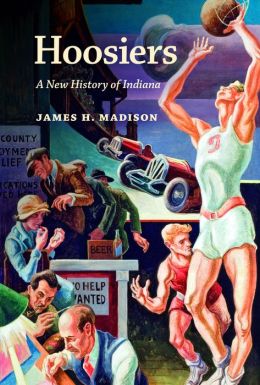

In the introduction to Hoosiers (co-published by Indiana University Press and Indiana Historical Society Press, and released in August 2014), Madison explains that he set out merely to “update” The Indiana Way, his first comprehensive account of the state’s past, published in 1986. “But simply updating that book proved unwise,” he writes. “Because Indiana has changed. So has the knowledge of our past.”

By way of example, he points to the mostly anonymous French fur traders and other settlers who were among the first Europeans to venture into America’s midsection. “A popular 1950s school textbook on Indiana history claimed that the French ‘in their happy-go-lucky, easy going ways … took little more thought of the morrow than their savage associates,’” a viewpoint apparently held over from the 18th-century French and Indian War, after which the losing colonists from Continental Europe left behind place names like Vincennes, Terre Haute, and Versailles, and not much else. Madison argues that new scholarship suggests the French approach to populating the Indiana frontier, while it did involve trade and intermarriage with native peoples (which today doesn’t seem like a bad thing), wasn’t exactly “lazy.” Stated more accurately: They didn’t share the Anglo settlers’ zeal for private property and thirst for whiskey. In fact, the French, who formed villages with shared farmland, were “a highly law-abiding people,” writes Madison. “Not so the Americans. With their coming, violent crimes increased. So too did dueling. No wonder the French viewed Americans as ruffians, prone to drunkenness and fighting. No wonder they found particularly revolting the American penchant for eye gouging.”

But while the French and their collectivism come out looking pretty good in this book, Madison’s isn’t a work of reflexive America-bashing from the effete academy. “Horse thievery, rape, and murder became commonplace in the emerging American backcountry,” he writes. “And in more than a few cases it was the Americans who struck the first blow.” But Native Americans—after whom the state is named, after all, and who ceded it only after a long, bitter struggle—do not emerge unsullied, either. During the Revolutionary War, although one British commander “urged his Indian allies not to harm women and children and to bring prisoners back alive, the conditions of frontier warfare were often those of total war, affecting all people regardless of age, sex, or race. Not only Indians but also white frontiersmen often considered murdering enemy women and children to be a legitimate method of war. Whites as well as Indians engaged in the practice of scalping and committed atrocities of savage proportions.” The verdict: Fighting over the property we now call Indiana brought out the worst in both sides.

Such account-settling runs through Madison’s portrayal of the people who have called this land home at one time or another: the coarse young men who carved livelihoods out of the frontier and the (remarkably fecund) young women who accompanied them in nearly equal number. The Quakers who welcomed and helped resettle African Americans from the slave-holding South, in a state whose residents staunchly opposed slavery and, later, strongly supported the Ku Klux Klan. The bold industrialists who ushered in a new economy on their broad shoulders and resisted humane reforms for the laborers, many of them children, who toiled in their factories.

“Some believed in things that never were, a history without tensions, a past that venerated cozy log cabins and pleasantly humming spinning wheels,” writes Madison, who, after nearly four decades of teaching and scholarship in the state, is probably the closest thing Indiana has to a historian laureate. In the following passages, adapted from his new volume, Madison introduces us to some of the earliest “Hoosiers” to whom the name properly applied, and who did in fact live during a time heavy on log cabins and spinning wheels—but not one without tensions. They are just a few of the tiles in the broad mosaic of Indiana identity that Madison deconstructs in the book. While some of those pieces might not be pretty, nearly all of them are intriguing in their complexity. And for forebears as with reading, we’ll take intriguing over pretty any day. —Evan West

Readings from Hoosiers: A New History of Indiana

By James H. Madison

“Git a plenty while you’re a gittin'”

“Old America seems to be breaking up, and moving westward,” an English newcomer wrote as he watched families traveling into the trans-Appalachian West. This movement westward shaped Indiana. From across the Atlantic Ocean to the North American continent, to the Appalachian Mountains, to the Wabash, Ohio, and Whitewater Rivers, to the shores of Lake Michigan they came. The stories of westward-moving pioneers remain at the core of what it meant and means to be a Hoosier.

Perhaps the most important aspect of the Indiana frontier was the degree to which it was a success. There was failure, to be sure—many individual failures that produced hardship and defeat. But for most pioneers it was a frontier of abundance. There was no starving time in Indiana. The land was rich, the forests and rivers were bountiful, and pioneers knew how to sow, reap, and profit. They came looking for their own land and the prosperity and freedom it promised. Looking back, one aged pioneer said: “At this time was the expression first used ‘Root pig or die.’ We rooted and lived and father said if we could only make a little and lay it out in land while land was only $1.25 an acre we would be making money fast.” Novelist Edward Eggleston created an elderly pioneer settler who, as she puffed on her pipe, recalled telling her husband, “Git a plenty while you’re a gittin’, says I. I could see, you know, that they was a powerful sight of money in Congress land.”

With good reason, pioneers developed a strong sense of optimism, a conviction that progress was natural, and a confidence that this was the best that America had to offer. Near the end of their lives, many would reflect on their decision to move to the Indiana frontier as proof of God’s blessing and as a guarantee that their lives and those of their children were better as a consequence.

They traveled across the mountains, down the rivers, and over the western trails and roads to the new state of Indiana. Historians would label it “the great migration,” one of the most consequential population movements in all of American history. Thousands of men, women, and children made the trek in the years following the War of 1812, for that war ended Indian resistance and opened new land for settlement. Indiana’s population grew substantially in those years, with the great bulk of the increase due to migration.

Three migration streams developed, and tended to sort out in a pattern that reflected geography, with southerners most heavily congregated in the southern part of Indiana, mid-Atlantic peoples in the central region, and New Englanders in the northern part.

The earliest settlers came from the upland South, particularly Virginia and North Carolina. With the end of the Revolutionary War they trickled across the Appalachian Mountains, particularly at the Cumberland Gap, and made the first permanent settlements in Tennessee and the Kentucky Bluegrass region. Many of these upland southerners had family and cultural roots in southeastern Pennsylvania. During the eighteenth century, Scots-Irish and German Pennsylvanians moved southward into the Shenandoah Valley of western Virginia and then over the mountains. In the first decade of the nineteenth century, Virginians and Tar Heels crossed the Ohio River. With the end of the War of 1812, they surged across the Ohio and soon filled up southern Indiana. It was upland southern voices that pushed Indiana’s territorial government toward Indian removal, cheaper land, and more democracy. It was upland southerners who wrote the Constitution of 1816.

Indiana’s white southern population was not from the tidewater, slave-owning South. They had not sat on breeze-cooled verandas or attended fancy balls. Indiana’s newcomers were people too poor to own slaves, people who worked their own family farms, people with generations of experience making a living on the frontier, all the way back to northern England, northern Ireland, and Scotland. One such pioneer was Thomas Lincoln. Born in Virginia, he crossed the mountains with his family in the 1780s to the Kentucky frontier, where Indians killed his father, Abraham. Thomas moved several times in Kentucky and married another native Virginian, Nancy Hanks. In 1809 they had a son they named Abraham. In the fall of 1816, when Abe was seven years old, the family crossed the Ohio River into Indiana, settling on Little Pigeon Creek in present-day Spencer County. Like other upland southerners, Thomas Lincoln was attracted to Indiana by the rich land, by the security of the systematic federal land survey as stipulated in the Land Ordinance of 1785, and by the absence of slavery. And like most new settlers, he fit the Jeffersonian image of sturdy yeoman farmers attached determinedly to land, to free labor, to individual freedom, and to particular notions of equality and democracy.

Also moving from the South were African Americans. Many came as property of their Virginia or Kentucky owners. Some arrived as emancipated or escaped slaves. Others had never known slavery. Free blacks moved west for the same reasons whites did, but with a more pointed quest for freedom, especially as antiblack laws and practices flourished in the South after Nat Turner’s slave uprising in Virginia in 1831. African Americans devised migration strategies based on two criteria. The first was access to land, which they knew offered economic opportunity and the possibility of freedom—at least the freedom to be left alone. The second strategy was to locate near Quakers. The Society of Friends had developed strong antislavery beliefs during the American Revolution. Some Quakers in the South freed their slaves and moved west, many from North Carolina. In Indiana the first Yearly Meeting, in 1821, formed a Committee on the Concerns of People of Color and soon began offering financial aid and other assistance to blacks migrating from the South. Many Quakers settled in eastern Indiana. It was no accident that so did free blacks. By 1850 Wayne County had the state’s largest number of Quaker churches and the largest number of African Americans.

The early upland South migration meant that Indiana was settled from the south to the north, filling up like a glass of water. Southern Indiana was settled first. From the Indiana side of the Ohio they set off on trails and traces into the interior. Most important was the Buffalo Trace, crossing the state from the Falls of the Ohio opposite Louisville to the Wabash at Vincennes. Upland southerners found the hilly, unglaciated sections of southern Indiana most like the area they had left in soil, terrain, and vegetation.

Central Indiana was sparsely settled at the time of statehood because of the greater difficulty of access and because of Indian claims to the land. The New Purchase Treaty of 1818 opened the region to white settlement, and gradual improvements in transportation enabled thousands of newcomers to claim the rich lands of the Wabash Country and the Tipton Till Plain. Many were mid-Atlantic pioneers who set off from Pittsburgh and other points down the Ohio in boats of all kinds. Some also traveled overland through Ohio, following the roughly marked traces to Cincinnati, or later through Columbus on the route that would become the National Road.

The northern region of the state was settled last, in the 1830s and 1840s, as it was both the final refuge of Indian tribes and the least accessible part of Indiana. Population growth may also have been retarded by the fact that speculators bought large tracts of land in parts of the area, especially in the northwestern prairie counties. Wet and swampy land around Fort Wayne and in the Kankakee region created a formidable barrier to settlement. With Indian removal and improved transportation in the 1830s, pioneers began to farm fertile lands in the St. Joseph Valley, the Door Prairie, and other areas of the north. Many agreed with pioneer agriculturist Solon Robinson that “The north end of Indiana will most certainly become the garden spot of the state.”

Indiana’s pioneer population thus consisted of peoples drawn from throughout the United States, but in significantly different proportions. The 1850 census showed that of the American-born residents who had migrated to the state, nearly 3 percent had come from the New England states, 20 percent from the mid-Atlantic states, 31 percent from Ohio, and 44 percent from the southern states. Indiana’s southern-born population was larger in both absolute and relative size than that of any other state in the Old Northwest, a central element in the claim that Indiana was the most southern of northern states.

Each of the three major settlement groups brought with them a distinctive culture. That of southern Indiana was the most distinct. Upland southern patterns of word usage and pronunciation, religion, place names, food, amusement, and methods of constructing barns, houses, and corn cribs were firmly implanted in southern Indiana by 1820. The cultural baggage that southerners brought with them included strong family ties, a masculine and patriarchal culture that included gender inequality and tended to violence, personal loyalty, attachment to traditions, and a commitment to personal liberty that sometimes drifted toward political libertarianism. An Englishman crossing southern Indiana in 1818 concluded that “The simple maxim, that a man has a right to do any thing but injure his neighbour, is very broadly adopted into the practical as well as political code of this country.” Upland southerners in Indiana had less use for government, and certainly no use for the kind of aristocracy they saw in [first Indiana Territory governor] William Henry Harrison, his Grouseland home, and other affectations of plantation gentry. They desperately wanted to own land, since they believed that land was essential to their family’s well-being and the egalitarian society they prized. White upland southerners abhorred slavery as competition to free labor. They also wanted to distance themselves from African Americans. The upland southern culture in Indiana changed over time, but elements of it persisted into the twenty-first century.

Northern Indiana did not develop such a solid New England cultural foundation, but elements of it were there by the mid-nineteenth century. Fruit trees and clocks, dairying and haymaking, a preference for cider rather than whiskey, a greater interest in commerce and more active government—these and many other factors signaled Yankee presence. Men milked cows, a chore considered women’s work among upland southerners. At butchering time, New Englanders usually cooked and ate the innards; southerners threw them to the dogs but fried the intestines or chitlins. Yankees could become impatient with southerners who seemed lazy and backward. An extreme example was the Hoosier politician Godlove Orth, who wrote from Lafayette in 1845 that “the enterprising Yankee of Northern Indiana, despises the sluggish and inaminate [sic] North Carolinian, Virginian, and Kentuckian in the Southern part of the State.”

Central Indiana was especially important as the place where the cultures of the upland South, the Mid-Atlantic, and New England mingled and mixed, causing each to change. Such was the case of an upland southerner in Indianapolis who thought his Yankee wife’s family “mighty good people, only their ways and their talk was so diff’rent.” Adding spice to the mix were the Irish and German immigrants sprinkled across the state. The result was a distinctive culture, one that was neither northern nor southern but rather western (later to be designated midwestern) and Hoosier.

“No soil produces a greater abundance than that of Indiana”

Making a home on the Indiana frontier was a job that required particular kinds of knowledge, skills, tools, cooperation, and hard work. The first challenge facing the pioneer was deciding where to settle, a decision that tended to be based on both accurate information and inaccurate hearsay. Both kinds of advice were found in the travel books that began to appear after the War of 1812. Most boasted about the advantages of the frontier. John Scott’s Indiana Gazetteer, published in 1826, not only assured potential newcomers that “no soil produces a greater abundance than that of Indiana” but also provided optimistic, detailed, and sometimes inaccurate descriptions of the counties, towns, and natural features of the state. Likely more important than travel books was advice from relatives and friends who had preceded the westward-moving migrant. They told about the availability, richness, and price of land, the quality of the timber and water, the access to rivers and streams, and the dangers of fever and milk sickness. As a consequence, a chain of migration pulled kin and neighbors together from the old place to the new.

Although some pioneers simply squatted where they wished, most understood the wisdom of obtaining clear land title. Federal policy had made landownership increasingly easy, for it had been based since the Land Ordinance of 1785 on the assumption that economic democracy was important to political democracy, that both had some relationship to ready access to the public domain.

The first land sales at Indiana offices occurred at Vincennes in 1807 and at Jeffersonville in 1808. The great migration following the War of 1812 brought a rush of eager purchasers, lending reality to the popular phrase “doing a land office business.” The Vincennes office sold 286,558 acres in 1817, leading the nation in sales. With the opening of central Indiana by the New Purchase Treaty, Congress created land offices in Terre Haute and Brookville, later moved to Crawfordsville and Indianapolis. During the 1820s, Indiana’s land offices sold nearly 2,000,000 acres, most of it in the central portion of the state. By the 1830s the busiest office was at Fort Wayne, selling acreage in the northern third of the state. The Fort Wayne office, which had disposed of only 18,836 acres in the 1820s, sold 1,294,357 acres in the boom year of 1836. Relatively easy access to cheap and productive land was fundamental to rapid settlement. The process constituted one of the federal government’s greatest gifts to Indiana.

Hardly anyone pioneered alone. Individual men or groups of men sometimes went ahead to select a site and construct a shelter, clear some land, and plant a crop. But these trailblazers were soon followed by women and children, so that the sex ratio of men to women on the frontier was only slightly unbalanced, and for only a short period of early settlement. Women may have been more reluctant to move, more hesitant to break family ties, and more attuned to the hardships ahead. But move they did, so that the basic unit, often from the first plunge into the wilderness, was the nuclear family—husband, wife, and minor children.

The frontier family was young and large. Younger men and women were more likely to seek their start in the West, often soon after the wedding ceremony. Pioneer women married younger and, as a consequence, had more children than did women who remained in the East. It was not unusual for a frontier woman to begin bearing children at the age of eighteen and to give birth every other year until her mid-forties. The number of children and their spacing were determined less by contraception, which was seldom practiced, than by the biological constraints of pregnancy, breastfeeding, and finally menopause. As a consequence, the birthrate in Indiana in the 1810s ranked among the highest in the world. For the early frontier period, large and youthful families were the norm. They constituted the basic economic and social unit of pioneer Indiana.

“I furrowed out and my wife dropped the corn”

Food from the forest was critical in surviving the first few years on the frontier. Culturally, however, the pioneer was not a hunter or gatherer but a farmer. From the beginning, the family set to work to till the soil in a regular and controlled manner. The pioneer farmer’s first task, however, was not to plant but to chop. Trees covered most of the land and provided items necessary for family life, including shelter, tools, utensils, and fuel for heating and cooking. So essential were trees to the material culture that emigrants were reluctant to settle on Indiana’s treeless prairies. But trees were also an obstacle to be removed.

Clearing land was the hardest and most time-consuming job. The woodsman’s ax—a tool placed on the state seal—was more useful on the frontier than a rifle. Abraham Lincoln later recalled that when he arrived in Indiana in 1816, he “had an ax put into [my] hands at once” and “was almost constantly handling that most useful instrument.”

Clearing the land produced much more timber than could be used for fences, buildings, or fuel, however. Pioneers cut felled trees into movable rounds and rolled them onto piles to burn. This logrolling was often a group activity that brought neighborly sport and socializing to a difficult task. Burning wood made smoke ever-present on the frontier and was as much asign of progress as the outpouring of factory chimneys would be to the next generation.

Once the land was cleared, it had to be broken. Farmers from the upland South favored a jumping shovel plow, pulled by a horse or two, which would cut through small roots but jump over large ones. Yankees tended to use a heavier cast-iron plow, pulled by oxen, which would cut through even a four-inch oak root. On prairies where there were no trees, thickly rooted grass required special sod plows and new techniques of plowing. Whatever the method, the soil had to be scratched and turned by a plow, with the clumps and clods broken up with a harrow. It was then ready to plant. One young pioneer father remembered the first planting: “I then fixed a little crib on the plow so that we placed our first child I furrowed out and my wife dropped the corn.”

Corn was the first crop. It was the base of agriculture for the pioneers, as it had been for Native Americans, and as it has remained down to the present. Upland southerners were especially attached to corn, but it was king throughout the state. It was a good choice. Corn grew easily in Indiana’s soil and climate, even when planted among trees and stumps in a deadening. It produced perhaps double the food per acre of any other grain and quickly became the staple item in the diet of humans and animals. Corn harvesting meant long, lonely days in the field in fall, but also a husking bee when neighbors gathered to work and socialize. One pioneer recalled that “the corn … is thrown into a pile often six feet high and about 200 feet in length. The owner provides himself with 2 or 3 gallons of Whiskey in a stone jugg, kills a pig or 2 or sheep, some dozen chickens or more.”

Pioneer women pounded and grated corn into meal, which they boiled to make mush and baked to make johnny cake and corn pone (baked “hard enough,” wrote [nineteenth-century author] Baynard Rush Hall, “to do execution from cannon”). With the outer shell removed, they made the grain into hominy for boiling or frying. Corn was also the basis for whiskey, which according to one disapproving traveler in Indiana was “drunk like water” even though it “smells somewhat like bedbugs.” Whether in liquid or solid form, corn was usually on the table whenever a family sat down to a meal.

Corn not consumed by the family was fed to the livestock. Pioneer families brought with them or soon acquired a milk cow and some chickens. But most important, they raised hogs. Commonly known as razorbacks or landsharks, they were long-legged and wiry, fleet of foot, and able to forage for their own food in the woods, where they subsisted on mast and roots. A few weeks prior to slaughter, the farmer penned them up to fatten on corn. Hog butchering usually occurred just before Christmas, with the first cold weather, and was often a cooperative task shared by neighbors. Families savored fresh meat in the weeks following butchering, a time when many men regained weight lost during the harvest. Most of the pork they preserved with salt and smoked. Throughout the year, a day seldom passed that a pioneer family did not eat pork. As a symbol of Indiana’s pioneer era, the hog deserves top billing alongside the log cabin. Today’s celebrated pork tenderloin sandwich provides a secular form of communion at the ancient Hoosier altar.

“Whose ear?”

“The Hoosier’s Nest,” painted by Marcus Mote sometime in the mid-to-late 1800s to illustrate the John Finley poem of the same name.

They called themselves “Hoosiers,” these citizens of Indiana. Generations of curious researchers have failed to identify the word’s origin or meaning. Many have offered serious speculation and light amusement. One oft-told story is attributed to “the Hoosier poet,” James Whitcomb Riley. After a brawl in a pioneer tavern that included eye gouging, hair pulling, and biting, a bystander reached down to the sawdust-covered floor and picked up a mangled piece of flesh. “Whose ear?” he called out. Perhaps it’s just as well to have a mystery around something so important.

The word was widely used in conversation and in print by the early 1830s, including in a widely cited 1833 poem titled “The Hoosher’s Nest.” Two years later a newcomer to Richmond explained in a letter to family back home in Pennsylvania that “old settlers in Indiana are called ‘Hooshers’ and the cabins they first lived in ‘Hoosher’s’ nests.” She added, “It takes a year to become a Hoosher.” Near La Porte about the same time, a traveler “in the land of the Hooshiers” wrote that the term “has now become a soubriquet that bears nothing invidious with it to the ear of an Indianian.” Hoosiers have retained the nickname into the twenty-first century, when state records showed twenty-six hundred businesses using “Hoosier” in their official name.

It’s true that at times some have ascribed negative connotations to the word, using it to suggest an uncouth, rustic people, but a writer in 1962 thought that it “continued to mean friendliness, neighborliness, and idyllic contentment with Indiana landscape and life.” Most Hoosiers today embrace it proudly as part of the distinctiveness of the nineteenth state, mindful that few other states have such a brand and asset.

A reception and book signing with author James H. Madison and Hoosiers: A New History of Indiana will be held at the Indiana History Center (450 W. Ohio St., Indianapolis) on September 24, 2014. To RSVP, call 317-233-5658.

Madison’s Hoosiers: A New History of Indiana excerpted with permission from Indiana University Press. For more information or to purchase the book visit IUPress.Indiana.edu.

Madison photo by Dale Bernstein, design by Todd Urban; “Hoosier’s Nest” painting courtesy Indiana University Press