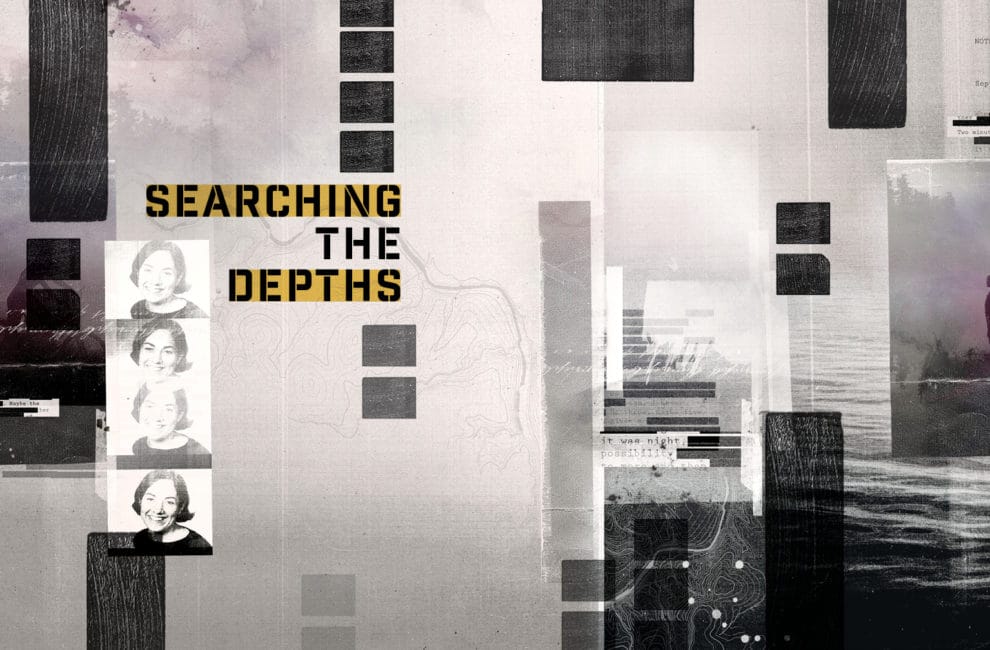

Illustration by Cliff Alejandro

How The Jill Behrman Case Informed Michael Koryta’s New Novel

Supposedly, the most-loathed question for a writer is: “Where do you get your ideas?” I won’t deny there are times when that has been true for me, when I end up foundering through the explanation of a process I don’t entirely understand myself, and trying to avoid saying things that will make me sound like a lunatic, even if they’re true, such as “when the characters start talking to me …”

How It Happened by Michael Koryta

The inspiration behind my latest novel, How It Happened, has no such mystery for me, and the better question isn’t where I got the idea, but what took so long to give in to it. This book, the 13th I’ve published, has been knocking on the door for more than half my life now. I was 17, a junior at Bloomington High School North, and Jill Behrman was 19, a Bloomington South graduate and freshman at Indiana University, when she disappeared on a beautiful late-spring morning while on a bike ride. Her bicycle was found alongside a country road near where I grew up, an area where I did a lot of hiking. There are rolling farm fields bordered by woods, a creek, an old church, and a cemetery on a high hill.

For days, our neighborhood was surrounded by roadblocks, and friends and I joined the volunteer search parties. Not long after her disappearance, I was in a car with my family when we passed a man looking into that creek not far from our house. He was standing alone, staring into the water. I don’t remember if I asked about him or if my mother did, but I remember my father answering in a very soft voice: “That’s Jill Behrman’s father.”

Eric Behrman didn’t even glance at our car. He just kept looking at the water.

Two years later, the case remained unsolved, and now I was a 19-year-old freshman at Indiana University, working part-time at the Bloomington Herald-Times and attempting to write my first crime novel when, on another beautiful spring day, rumors began to circulate that police divers were entering the waters of a rural creek in a different area of the county. All of the full-time reporters were immersed in stories and deadlines and couldn’t pause to chase a rumor. I decided that I’d skip my next class and go see what I could find. My reporting mentor warned me that if there was any truth to the talk of a police search, the road would probably be closed. So I parked on a different road and walked through the woods to reach the creek. I learned quickly that the FBI does not appreciate such displays of ingenuity from reporters.

The article I wrote about that scene was my first front-page story, and so this is the first sentence I ever published for any sizable audience: “A large team of divers searched all day Tuesday in Salt Creek near Lake Monroe after authorities received a tip in the 22-month investigation into the disappearance of Bloomington resident Jill Behrman.”

Before they chased me away from the scene, another lasting image caught my eye: an FBI agent staring into dark water and wondering about the truth.

It had been nearly two years since I’d seen Jill’s father doing the same thing.

I thought about that a lot. Still do.

As a newspaper reporter, Michael Koryta covered the years-long search for Jill Behrman’s body in Salt Creek and elsewhere.AP photo/The Bloomington Herald-Times, Jeremy Hogan

The divers didn’t find Jill that day. Later that spring, the creek flooded, reaching record highs that disrupted the search. In the summer, police returned. I landed another front-page story when they began using side-scan sonar equipment to search those dark waters. They still came up empty.

In late summer, rather than give up on the search, the FBI and local police announced that they were going to do something nearly unprecedented in such investigations: build a dam and drain a creek. That’s how convinced they were that they had the right place. Locals donated money, equipment, and time to help. Police from many agencies worked side by side in brutal conditions as the water receded and a swamp replaced it—and no body was found.

On September 20, 2002—my 20th birthday—tornadoes ripped through the region. I cut class again so I wouldn’t miss the chance to write those stories. I did that a lot, trading the classroom for the newsroom. The storms that day brought an end to the search in Salt Creek. They eventually had to breach the dam for safety concerns, and water filled the area once more, and Jill was still missing.

It was a few months before police and the FBI explained what had led them to Salt Creek in the first place: They had a confession. A local woman told a vivid and horrific story about being one of three people, all of them high and drunk, riding in a pickup truck that collided with Jill. They had wrapped her in plastic, she said, taken turns stabbing her, and put her into the water. Then her bicycle was dumped in another area of the county, in that place where I’d been hiking since I was a kid.

The community reaction to the confession was horror and some measure of relief. Alongside the shock and outrage was the hollow consolation that at least now, after nearly three years, there was some closure. But there was still no body, and the Monroe County prosecutor declined to bring charges, citing a lack of physical evidence.

A few months later, a turkey hunter stumbled upon Jill Behrman’s bones in Morgan County, miles away from the site of all those painstaking searches, and miles away from her bike. On the day that Jill’s remains were identified, the woman who had given the original confession didn’t speak to the press. Her attorney, however, told reporters: “She was surprised at the development … without getting into a whole lot of details, I can say I still have faith in my client.”

What fascinated me about the lie was the amount of specificity that had been offered, particularly about the early hours of the night, those pre-crime hours before the three people in the truck had allegedly encountered Jill on her bike.

Ten days later, she formally retracted her story.

I was astonished by that retraction. Not because I had never heard of anything like it. I was a criminal-justice major, private investigator, and newspaper reporter. My education, formal and informal, was rooted in never taking statements at face value and expecting to hear lies. But that confession had been so vivid, visceral, and detailed. Attempts had been made to mitigate personal responsibility and diffuse it to the other actors in the crime while the tale was told, but what fascinated me about the lie was the amount of specificity that had been offered, particularly about the early hours of the night, those pre-crime hours before the three people in the truck had allegedly encountered Jill on her bike in the early morning of that beautiful small-town spring day.

A lot of those details checked out. Time and again, they checked out. The police detectives and FBI agents involved were experienced investigators who knew they were dealing with a notoriously unreliable narrator, and they had looked into every element of the story possible. I couldn’t shake that, imagining what it must have felt like to believe so deeply that you had the truth, and then have it taken away from you.

I began to understand the book that I wanted to write a little better then. I didn’t want it to be about a small-town tragedy that achieved national reach, although that’s certainly what Jill’s story became. I wanted to write about a confession that people believed was the beginning of the end, and proved to be anything but that.

I just couldn’t bring myself to start that book. Everything about the story, from my own memories to my sense of the town, was all too close. No surprise, then, that the story began to creep back to me the farther I got from Bloomington.

John Myers II was ultimately convicted of Behrman’s murder in 2006.AP Photo

Three years after Jill’s body was found and the infamous confession was recanted, an Ellettsville man named John Myers II, who had not been implicated in the confession—but who happened to be the cousin of one person alleged to have been in the truck, and an acquaintance of the two others—was charged with Jill Behrman’s murder. He was convicted in 2006 and is in prison today. During his trial, the woman who had told that vivid and horrifying tale, a story that had redirected the entire search and convinced so many that closure was at hand, took the witness stand, apologized to the Behrman family, and blamed the pressure from police for her false confession.

By then, I was gone from the newspaper, writing novels full-time, and living most of the year in Florida. The story didn’t remotely involve me any longer, and yet I came back from Florida for parts of the trial. I still wanted to write about it, but I couldn’t find my way into the narrative. Everything felt too real, too close to places I knew. How to begin? I was frozen there in a way I never had been with a book before. I knew that I didn’t want to write a fictional version of Jill Behrman’s tragedy, and most critically, I didn’t want anyone to think I was a novelist playing armchair detective. I did not, and do not, consider that to be fair to the families or investigators involved. But I had to write about the case in some way because it had been the dominant story of my life for many years.

There was a time when I envisioned writing the story as nonfiction, covering the investigation, trial, and conviction. I couldn’t write that book, though. The story as I knew it, my very brief and tangential but still emotional connection with it, was built on moments and images: a country road I knew so well, a father searching a creek, divers searching a different one, a community awash with rumors, an FBI agent and police detectives determined to bring closure to it all. And to write a novel, I had to step far away from it to get close to it again. That’s how a Midwestern tragedy found its way to the Maine coast, and how imagining a lobsterman and his daughter and an overgrown New England graveyard somehow guided me back to the story that has chased me for more than half my life. By changing the place and time, I was immersed in fiction, rather than trying to fictionalize a true story. But it is important for me to explain that I reached that story by going back to three distinct moments from reality:

A father staring into empty water.

A detective staring into empty water.

A woman who told them how it happened—and then said it had all been a lie.

Since the day I walked through the woods to find the dive team combing the dark waters of Salt Creek in search of evidence, I’ve published more than a million words in more than 20 languages. I’ve written novels, short stories, screenplays, articles, essays. But throughout, when people asked me what story stood out in my mind, what story lingered, I always pointed to that police-beat article far quicker than any book, short story, or script. That was the one that kept circling through my mind.

Why? Because I thought I’d helped write the beginning of the end. My readers felt the same way, I think. We believed her. When she told us how it happened, we were horrified, and we believed her.

Michael Koryta

It took me a while to understand that I was also writing about the past, and a world that doesn’t exist in Bloomington—or anywhere—anymore. When I was reviewing old newspaper stories for this piece, I came across an article in which a local resident spoke of feeling “haunted” by Jill’s disappearance. It had been only three weeks at that point, and already the community felt that way. The local wasn’t exaggerating; that was precisely the way the story settled over the town. Three weeks felt endless; no one could imagine it would be years before Jill was found, years before a conviction.

What stood out to me in that newspaper story wasn’t just the resident’s word choice, though, but the way she described dealing with her hope for answers: “The first thing I do every morning is go down and get the newspaper to see if they found her.”

That was how she expected to learn if anything had changed in the case. Going down to the mailbox to get a physical newspaper.

That quote made me realize something that should have been obvious for years—how much our world has changed since that late-spring day when an Indiana University freshman went missing and it seemed unthinkable. In our town? Her bike found on my road? No, not possible, not in Bloomington.

When it happened, the entire horrified community still went to check their morning newspapers in hopes of results. There was something jarring about that realization, because Jill’s disappearance doesn’t seem all that far off to me. But in reality, we were nearly two years from 9/11 and nearly a decade from the first iPhone. No Facebook, no Twitter. Bloomington wasn’t Mayberry—we had our crimes, our horrors. And yet …

When Jill Behrman left her parents’ home for that morning ride, she rode off into a world that seems antiquated in some ways now. Time moves fast. While I’ve explained all the reasons that I didn’t want this book to feel too close to the real story, there’s also a reason I want people to know where it came from. When I was struggling to write this essay, a friend asked me a wonderful question: What would you want Jill to know?

I would want her to know that people she never even met still think of her. That she is remembered by her community, and mourned by it.

Maybe that doesn’t matter, but I hope it does.

Click here to read an exclusive excerpt of How It Happened.