The Confessions Of Cleveland Bynum

Dr. Watson. It was a logical, perhaps elementary, conclusion that Fran Watson’s law students would piece the clues together and bestow upon her a wholly uninspired nickname. Never mind that she wasn’t a doctor.

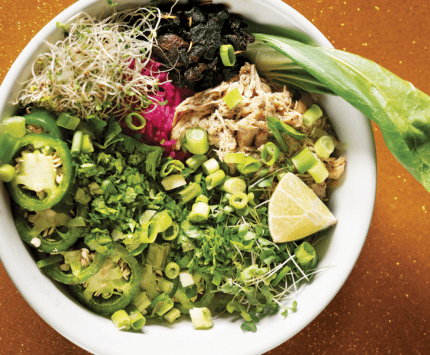

Cleveland BynumPhoto by Tony Valainis

What she was, long ago, was a bartender. Then she became Chief Public Defender of the Marion County Public Defender Agency. In 1995, she decamped to IUPUI, where she directed the Criminal Defense Clinic and launched the Wrongful Conviction Clinic in 2001. In that domain of the legal realm, she had become something of a legend: She had developed a reputation of solving long-dead cold cases, winning six exonerations in 16 years. Sometimes, her students would tease her about her last name, comparing her to the eponymous detective in the Sherlock Holmes novels. “Oh, Dr. Watson,” they would call her, laughing, as they made the connection. Few of them knew that Watson had, in fact, devoured those stories, along with Nancy Drew books, as a kid growing up in Jeffersonville. If she wasn’t reading about the pursuit of criminal evidence, she was digging for the prehistoric kind, combing the 390-million-year-old fossil beds that line the Ohio River.

One mid-October day in 2014, Watson showed up to work in Room 111J in Lawrence W. Inlow Hall at the Indiana University Robert H. McKinney School of Law in Indianapolis. Piles of letters and legal documents and files towered over her, some nearly two feet high. Like always, the plainspoken attorney seemed impossibly behind on her work. Each month, she received dozens of letters and case files from prisoners claiming innocence and asking for her help. The majority of the cases she agreed to take on dealt with a thicket of thorny legal issues that often lead to wrongful convictions: sketchy eyewitness identifications or jailhouse informants; police and government misconduct; junk science and false confessions. After decades of reading through letters like these, along with conducting prison interviews to vet inmates’ stories, Watson had come to develop what might just be the world’s keenest bullshit detector.

Among those stories that passed muster was that of Cleveland Bynum, an inmate at the Pendleton Correctional Facility and the man at the center of a 2000 mystery that produced five dead, two confessions, and one dramatic charge: The admissions of guilt had been fabricated.

That fall day in 2014, 13 years after Bynum was convicted, Watson was attempting to clear away the legal detritus on her desk when she came across a manila envelope addressed to her. According to the return address, the certified mail had come from a woman named Melissa Williams at 6237 Croquet Place in Indianapolis.

There, scientists ran it through probabilistic genotyping, a kind of test that can isolate mixed DNA strands. None of the DNA linked Pinkins or Glenn to the crime. The story had a made-for-Hollywood ending, with Watson and eight of her students posing for a picture with Pinkins. As Pinkins endured emotional interviews with reporters, Watson sat next to him, holding his hand. “This is a rarity,” Lake County Prosecutor Bernard Carter told a reporter on the day Pinkins was released. Carter showed up to shake Pinkins’s hand, shortly after his office had granted the man’s freedom. “Juries usually get it right. In this case, they didn’t get it right.” Over 16 years, Watson had lost the case to the state six times. On the seventh, she prevailed.

Back on that fall day in 2014, though, the evidence went looking for Watson. She opened up the Seal-It envelope, which had been postmarked in Peru, Indiana. Out popped a cellphone, two CDs, a letter, and a notarized statement. Watson loaded one of the discs into her computer. She clicked on a video file. It began to play. A man looked into the camera and read a statement that took Watson’s breath away:

Hi, my name is Gerald Terrene Mathews. I’m doing this with the good hope of making some of my wrongs right, if that is possible. Back during February of 2000, I committed a crime. I made a mistake I couldn’t fix, and now I have to clear my conscience. I couldn’t turn myself in because I didn’t want to go to prison. The worst part is that I hurt people and their family, and I need forgiveness whenever I pass away. My understanding is that an innocent man is doing the time I was supposed to do.

But among the most egregious—and violent—breaches of public trust came to light in July 2001, when the FBI announced yet another probe of the Gary police. That month, a 59-page indictment alleged that Gary Patrolman James Ervin had been serving as a hit man for the Zambrana drug ring beginning in the fall of 1997. Ervin was sentenced to life in prison for strangling rival drug dealers with an extension cord on the stage of a Gary nightclub, dumping their bodies in the trunk of a car, and then setting it on fire to burn on a Chicago southside street.

But among the most egregious—and violent—breaches of public trust came to light in July 2001, when the FBI announced yet another probe of the Gary police. That month, a 59-page indictment alleged that Gary Patrolman James Ervin had been serving as a hit man for the Zambrana drug ring beginning in the fall of 1997. Ervin was sentenced to life in prison for strangling rival drug dealers with an extension cord on the stage of a Gary nightclub, dumping their bodies in the trunk of a car, and then setting it on fire to burn on a Chicago southside street. The statement was notarized on July 24, 2014. Inside the envelope were two other notes, both apparently from the sender. The most detailed of the two read:

The statement was notarized on July 24, 2014. Inside the envelope were two other notes, both apparently from the sender. The most detailed of the two read: