Twin Suicide: A Tragic Symmetry

This story contains references to suicide. The National Suicide Prevention Lifeline is a hotline for individuals in crisis or for those looking to help someone else and can be reached at 1-800-273-8255.

He tried not to dwell on it, but deep down, Mark Lawrance feared that one day it would happen again. Police would arrive at his quiet home along Lake Maxinhall on the city’s northeast side with heart-rending news. That day came October 30, 2017, a little more than 24 hours since he had last seen his 32-year-old son, Joe.

As Mark settled into bed around 10 p.m. that Monday, his thoughts wandered from his workday ahead at the Indiana Chamber of Commerce, where he was senior vice president, to his wife, Jan, returning home the next day from a girls’ weekend in Arizona. He fell into a deep sleep, jolted awake just before midnight by a knocking on the front door. His body tensed; his mind raced.

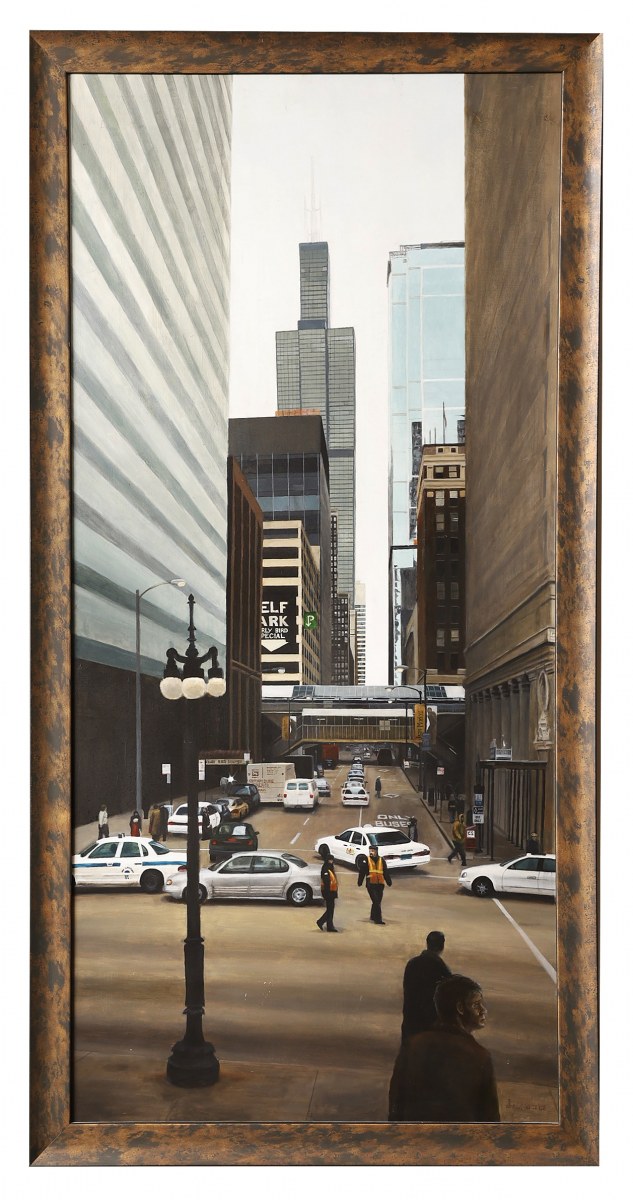

The security camera footage on his cellphone revealed two figures standing at the front entrance, one in uniform. He threw on his clothes and scrambled down the stairs and across the living room. He passed elaborate paintings Joe and his identical twin brother, Will, had done over the course of their lives, works that filled him with tremendous pride. But in that frantic moment, all he felt was panic.

When he opened the door, he saw the somber faces of a police officer and a chaplain. They didn’t have to say a word. “It’s my son, isn’t it?” Mark asked. They nodded. The chaplain confirmed Joe had taken his own life. Distraught and paralyzed by feelings of helplessness, Mark struggled to focus. But he knew he would have to make the hardest call of his life.

More than 1,600 miles away in Sedona, Jan sat in an art studio with three college friends, making decorative objects out of glass, laughing and reminiscing. Then came Mark’s call.

“And it was—boom—immediate screaming,” Mark recalls. “All I could hear was that scream.”

For the Lawrance family, what played out that night was tragically familiar. Joe’s death came six years, one month, and 20 days after his brother, Will, took his life at the age of 26. The family would soon return to Crown Hill Cemetery, surrounded once again by hundreds of mourners and a collection of art, grieving and struggling to make sense of what happened.

Jan remembers the weight of unbearable loss, the energy it took to simply stand up. It seemed unimaginable to lose them both, but there was a different feeling in the wake of the second twin’s death. “A silver lining was knowing they were back together,” she says. “I think they shared a soul and needed to be united.”

Joe and Will left behind more than memories and family photos. Their spectacular works on canvas and paper have become journals of sorts, revealing the twins’ hopes, dreams, passions, and the connection between them—along with a deteriorating mental state that their parents now strive to understand through their art.

MARK AND JAN met on spring break at a campground in the Florida Panhandle in 1975. Both were juniors, Mark at Indiana University and Jan at Michigan State. A weekend flirtation developed into a long-distance romance. They married a year later and started a family. Their daughter, Erin, arrived first, followed by a second daughter, Devin. The couple hoped for one more child.

Seven years later, Jan learned she was pregnant. She says she had a dream she was carrying twin boys. Not long after, her doctor remarked she was “a little bigger” than she should be. An ultrasound confirmed twins. Mark was giddy. He recalls lying on the floor, laughing and kicking his legs up in the air. It remains one of the happiest days of his life.

The boys arrived via cesarean section on May 17, 1985. Jan and Mark named the first-born twin William, after Mark’s father, and the second twin Joseph, after Jan’s dad.

The twins were identical. When they came home from the hospital, Jan put a dab of red nail polish on one of Will’s toes so Mark would know who was who. It didn’t get much easier identifying them as they grew. They had the same piercing blue eyes, sandy blond hair, and lean build.

When the twins were babies, Joe and Will were indistinguishable.Photos courtesy the Lawrance family

Joe and Will soon morphed into “Joe-Will,” a nickname they shared because so many people couldn’t tell them apart. They also shared an inseparable bond, common in twins, especially identical ones. Erin says as kids, the boys had their own language. They could look at each other and know what the other was thinking without uttering a word. When one got hurt, the other cried just as hard. They were always together.

While Mark and Jan are gregarious and outgoing, the boys were introverts. Still, their childhood was full of activities. They played soccer, baseball, and basketball, and loved camping and boating. Both joined the Boy Scouts, with Will advancing to Eagle Scout.

But when the twins discovered what they could do with a pencil and sketchpad, they were hooked. They could immerse themselves for hours, experimenting with different mediums and subject matter. Art provided them the means to interact with the world around them. “Maybe they couldn’t always tell you what they were thinking or feeling,” Jan says, “but their artwork was telling a big story.”

She first recognized their artistic talent in the cartoons each sketched in middle school. Jan marveled at the drawings, and their delight in creating characters and communicating with the stroke of a pencil or paintbrush. Mark’s a-ha moment came when the twins were in eighth grade and Joe shared his 3-D sketchbook. He had imagined buildings with vertical and horizontal girders, with all the perspective correctly drawn. Mark recalls the depth of detail as “just incredible,” especially for a 13-year-old with no formal training.

Though bright and inquisitive, the boys sometimes struggled to focus. A teacher told Jan that while Will was the smartest kid in the room, he couldn’t stay on task. Both boys were diagnosed with attention deficit disorder and prescribed medication. Art proved therapeutic as well. It kept their hands busy, their minds attentive. And, as they became more proficient, it ignited their passion.

Others also began to take notice of their burgeoning talent. Basil Smotherman met Will and Joe at a summer basketball camp he coached. He had to put tape with their names on their shirts to tell them apart. A few years later, he encountered them at North Central High School, where he taught art. When a colleague told him about the incredibly talented twins, Smotherman recognized them immediately, still finding it nearly impossible to tell one from the other. “They were always walking around together, connected, the kind where one twin finishes the other’s sentences,” he says.

Smotherman quickly discovered the Lawrance twins shared an outsized talent as well as their indistinguishable looks. He thought of them as prodigies. “They had something innate,” he says. “They just did it intuitively.”

Joe and Will thrived at North Central, taking every art class available, including two years of AP art courses. They excelled in everything, whether it involved drawing, painting, or sculpture.

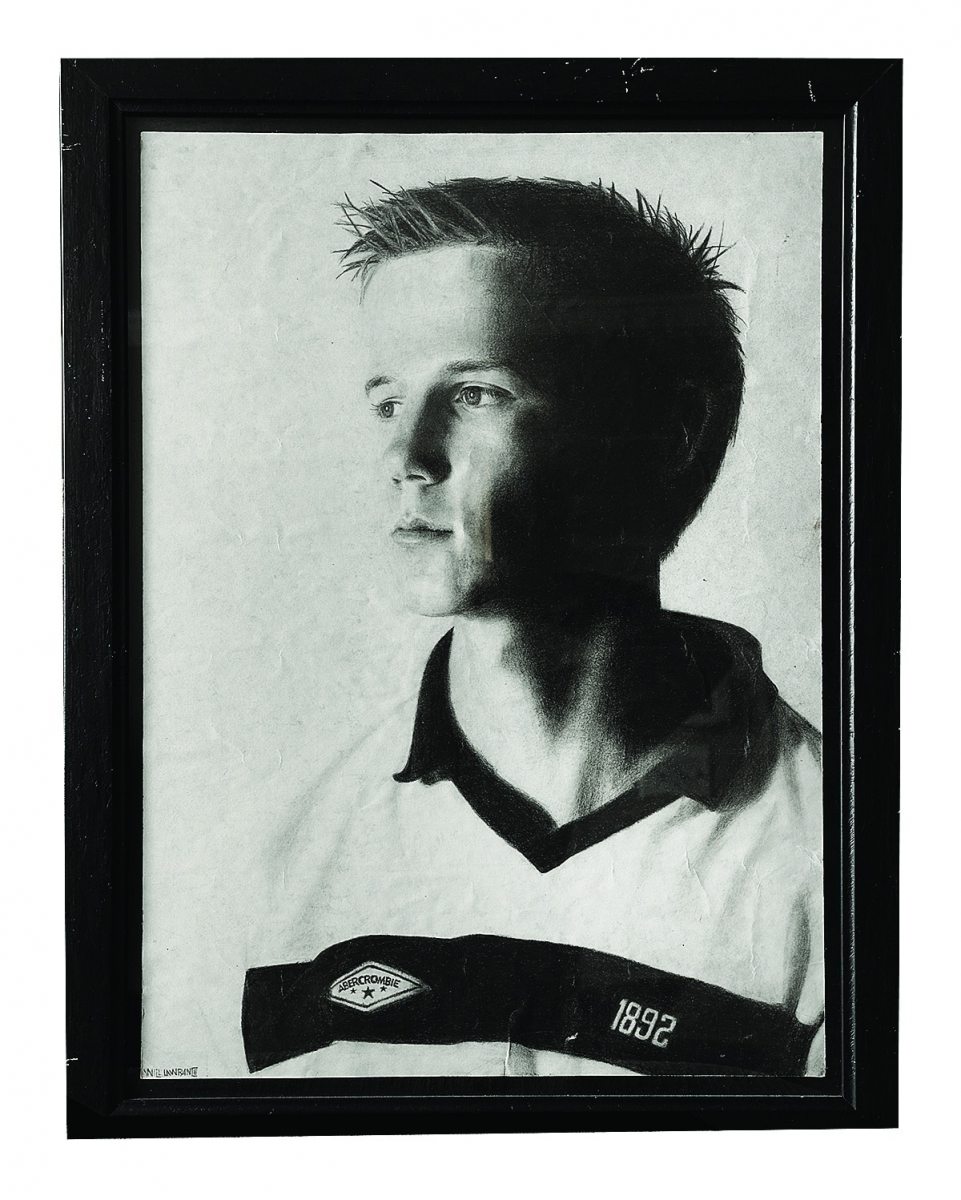

Smotherman says that when it came to draftsmanship or drawing, they were way ahead of the curve. Not only could they duplicate something from a print, but also from observation. And despite their almost painful shyness, the twins never shied from revealing themselves through deeply personal works, including self-portraits that exposed their flaws. One Will did was a 4-foot by 6-foot oil painting that the Lawrances affectionately call Big Face. It captures the spiky, unruly hair and pimpled, unsmiling face of a teenage boy—a mirror image of the artist who painted it. After repeated prodding from his sister, Erin, Will entered Big Face in the Smithsonian Institution National Portrait Gallery’s first-ever portrait competition in 2006. It ended up being one of the finalists.

A 4-foot by 6-foot oil painting by Will that the Lawrances affectionately call Big Face.Art provided by the Lawrance family

“I think it made the painting that much stronger to drop his guard and say, ‘This is who I am,’” Smotherman says. “Being honest is part of being an artist. They were able to put raw feelings into their art and were wise beyond their years.”

Joe used magazines he cut into thousands of strips to create one of his senior-year portraits. Jan says that while Joe knew how to do realism by mixing paint, “This was like, ‘Look what I can do by taking existing colors from a magazine and getting the shadowing and gradation just by the size and shape.’” It won a Scholastic Art Competition award and was later displayed at the Corcoran Gallery in Washington, D.C.

Both portraits depict a certain forlornness, the deep, penetrating eyes of two young men seemingly in search of something beyond their reach. “Even at the time, my reaction was, Oh my, the way they portray themselves as dour and sad,” Jan says.

In Will’s self-portrait, in particular, Mark noticed a concerning look. “I think it was really him inside,” he says, “an artist who had depression but wasn’t diagnosed at the time.”

Both portraits depict a certain forlornness, the deep, penetrating eyes of two young men seemingly in search of something beyond their reach. “Even at the time, my reaction was, Oh my, the way they portray themselves as dour and sad,” Jan Lawrance says.

WITH HIGH SCHOOL graduation approaching, Joe and Will both set their sights on The Cooper Union, a small, prestigious college in New York City’s East Village, renowned for its architecture, art, and engineering schools and highly selective admissions process. Those applying to the art and architectural schools must complete a home test. Applicants are given three to four weeks to finish and return several visual projects.

Joe applied to the School of Architecture and Will, the School of Art. Joe was accepted. Will was not, nor was he after he applied again the following year. Though Will never verbalized his feelings, the Lawrances believe the rejection left him deflated.

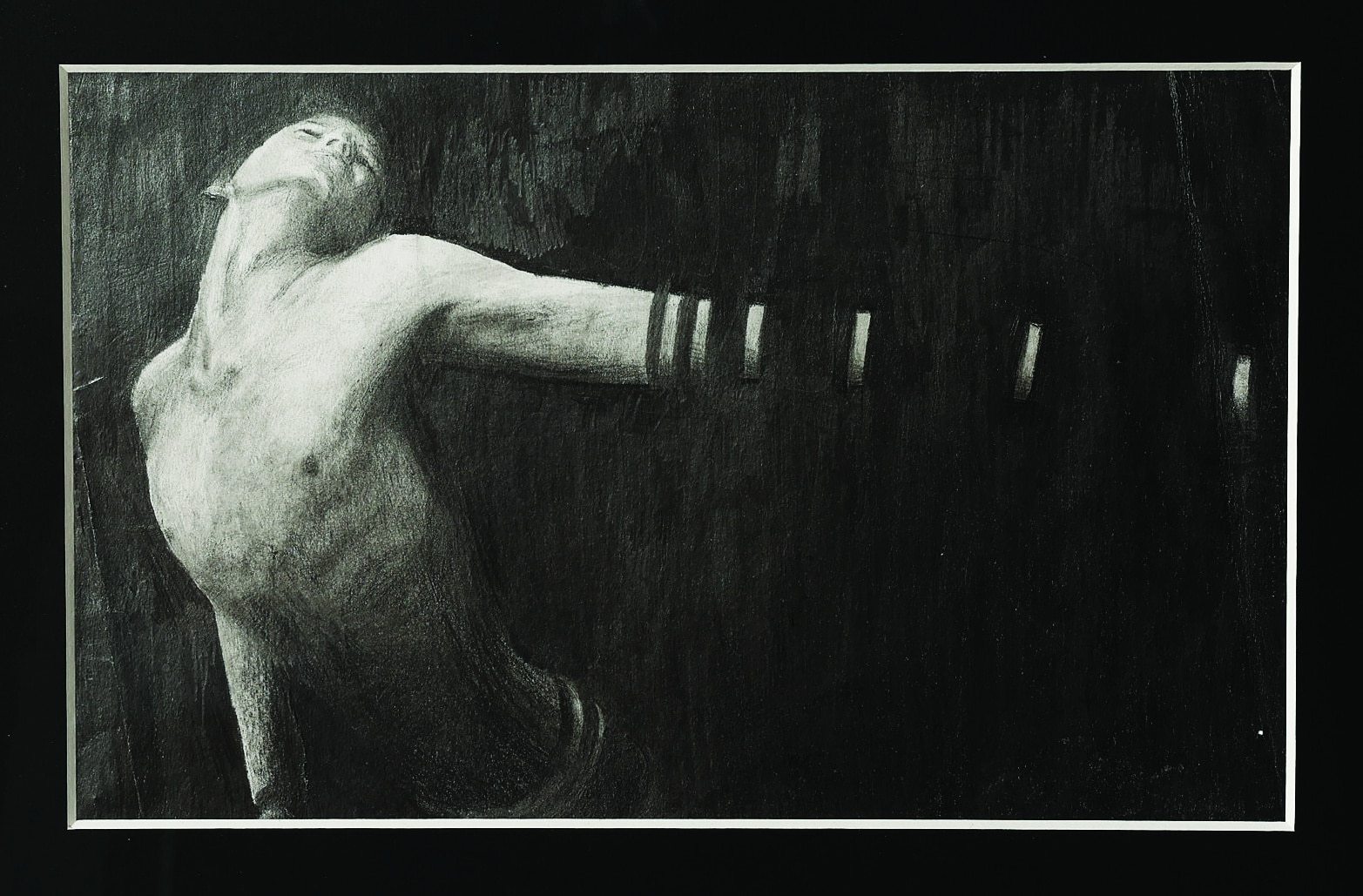

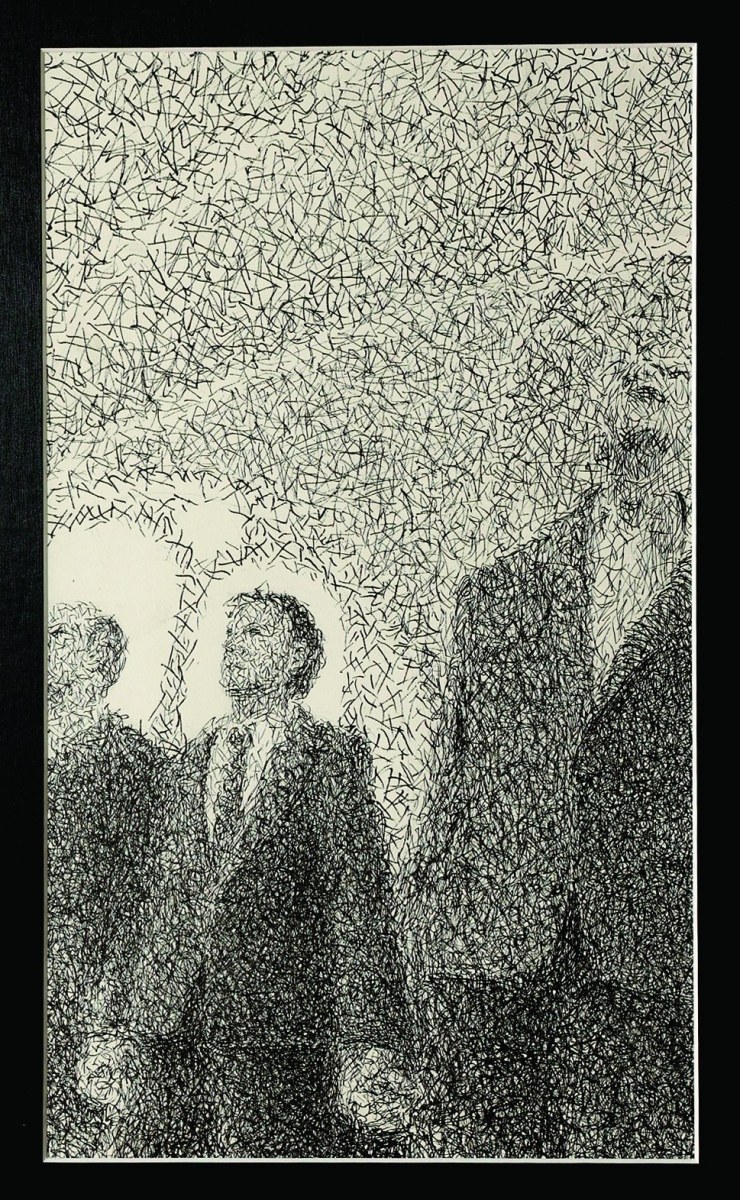

One of the artworks Will submitted as part of his home test the second time was a pen-and-ink piece. It showed him and Joe dressed in suits, holding hands, and standing just inside the Great Hall of The Cooper Union. Will is gazing up at the ceiling, in a way Jan describes as showing anger or pleading. Another of Will’s submissions depicts the twisted torso of an anguished young man, his left arm extended, straining to grasp something just out of reach, but being pulled apart, his forearm seemingly serrated, disappearing in sections. When Jan saw it, she saw the pain of separation. “I thought, He really wants to get to New York to be with Joe,” she says.

Despite the twins’ longing to attend The Cooper Union together, Jan and Mark believed it might be good for them to shine on their own and to discover their individual likes and needs. But looking back, Jan sees the start of college as “the beginning of the real struggle.” Will began at Ball State University but transferred the following year to the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, which better matched his artistic goals.

Devin and her husband, Jason Mandel, lived in Bucktown, a historic Chicago neighborhood not far from Will’s residence. Devin looked forward to spending time with her brother. Right before he moved to Chicago, she told him she had one question for him, and before she could ask it, he answered, “yes.” Will was gay. Devin said the family had suspected this and it wasn’t an issue for them. She just wanted to make sure Will knew that.

Living in student housing on State Street close to the Art Institute, Will loved being in the heart of the city, where Chicago’s history, architecture, and vastness were evident. It also afforded him anonymity. He could easily blend in while discovering a rich array of subject matter for his plein air paintings.

Will’s curriculum was demanding, but he seemed to rise to the challenge. He often joined Devin and her husband for Sunday-night dinner. Sometimes he returned home for a weekend in Indianapolis. During his time in Chicago, he also managed a trip or two to visit Joe in New York City. At the time, his family felt Will was in a good place, mentally and emotionally.

Joe knew no one in New York when he arrived at The Cooper Union his freshman year, but he made fast friends with a handful of other aspiring architects, including Stephen Martin. Martin describes Joe as a brooding soul who also knew how to make you smile. He says Joe’s laugh “had this way of bursting out of him very easily, which put everyone in a good mood.”

While Joe never drank alcohol in high school, that changed in college. It started with social drinking and progressed to bingeing. In retrospect, Mark believes Joe used alcohol to cope with his grueling schedule and Will being 800 miles away.

Joe’s moods could turn dark and erratic when he drank heavily, which he did with increasing frequency. And he could throw down liquor easily. Martin remembers seeing Joe consume a bottle of Jack Daniel’s in a night.

Martin, who has a twin sister whom he is close to, says if Joe was having a hard time being away from Will, he never mentioned it. Martin just knew architectural school was stressful, and Joe was a perfectionist. He admired his friend’s genius, how the artist and architect worked in tandem. “Joe had the ability to be incredibly precise in his work, but also leave wonderful marks of craftsmanship on the edge,” he says. “Every architectural drawing he made was full of smudges, ink smears, and graphite stains that would make it even more powerful.”

But Martin says Joe often agonized over projects and became paralyzed. When he couldn’t find a solution, he disappeared. “Sometimes, he’d find clarity, but it would be a dark process to get there,” Martin remembers, adding that if Joe came back with a painting, “it was the most beautiful thing you’d ever seen, but other times he’d come back empty-handed and heartbroken.”

At the start of his sophomore year in fall 2004, Joe started skipping class and drinking even more. In October, heavily under the influence, he attempted suicide. His friends found him and got him to the hospital. Jan and Mark left for New York immediately. Mark describes it as “a total shock.” Joe never let on he was floundering, nor did he ask for help. The immediate goal was to get him healthy.

Ultimately, Joe didn’t want to return home. He wanted to stay at school. His doctor agreed it was in Joe’s best interest if he remained under the supervision of a therapist and attended counseling and Alcoholics Anonymous meetings. He also began taking medication for anxiety and depression. For a while, he seemed to be holding his own. But during the spring semester of 2006, Mark and Jan received another call from one of Joe’s friends. Once again, heavily intoxicated, Joe had tried to take his own life. This time, the Lawrances brought him home and placed him in outpatient treatment. He didn’t return to The Cooper Union until the fall semester.

Will was in Chicago when he learned about Joe’s first suicide attempt. Devin says they wrapped their arms around each other and cried. Will was shook up and bewildered. Why didn’t Joe tell him he was struggling? When Devin asked Will if he had ever thought about taking his life, he was adamant: He would never do that. She felt she had Will’s promise.

Devin says Joe later told her he didn’t want to die, but he also didn’t want to wake up. “It was his way of saying life was too much.”

The Lawrances don’t know how much their sons talked to each other, if at all, about Joe’s attempts, but it clearly rattled Will. While at the Art Institute, he reached out to Jan at one point, saying he, too, needed help. He began seeing a therapist in Chicago. Like his brother, he also started taking antidepressants.

Joe’s leave of absence left him further behind in credits. He cut back on his class load, but was determined to stick with it. The Lawrances credit drug therapy, counseling, the support of faculty, and Joe’s staunchly devoted friends with helping him stay on track. But alcohol would remain a problem, his go-to coping mechanism for depression and anxiety.

His partner told the Lawrances that when Will was using, their kind, soft-spoken son’s behavior could turn erratic, shifting from flighty and dazed to angry and belligerent.

WILL GRADUATED in spring 2008 at the height of the worst financial crisis since the Great Depression. When he returned to Indianapolis, he knew his fine arts degree wouldn’t pay the bills. So he took a job with the Pratt Corporation, traveling across the country installing signs for national retailers. It’s where he met his partner with whom he would share an apartment. Will also did several commissioned art pieces and looked for opportunities to show his work. Ultimately, he still aspired to make his living as a full-time artist.

Joe graduated in May 2010, came home, and moved back in with his parents. He landed a job at a small architectural and design studio in Zionsville. A year later, he moved to a leading architectural firm in Indianapolis, where his portfolio would grow to include a renovation at Eli Lilly’s downtown campus and several projects at Indiana University.

Mark and Jan were glad to have both sons back in Indy. While they still worried about Joe, they had little reason to worry about Will—until early June 2011. That’s when he told them he had begun using drugs called bath salts and couldn’t stop. The cheap, mind-altering synthetic compounds with names like Cloud 9 and Scarface had become ubiquitous at gas stations and head shops. When Will began using them, they were legal. Will claimed the powerful stimulant kept him hyperfocused and allowed him to get more done, but his parents suspected it was a way to deal with the anxiety and stress he was feeling. Either way, Will quickly became hooked.

His partner told the Lawrances that when Will was using, their kind, soft-spoken son’s behavior could turn erratic, shifting from flighty and dazed to angry and belligerent. The Lawrances got Will into outpatient treatment that June, just ahead of a new Indiana law banning bath salts. But while he was still in treatment, clean for 17 days and on a lunch break, Will drove by a southside gas station with a sign announcing, “Bath Salts Back on the Shelf.” He pulled over, went inside, bought the drug legally, and relapsed. The manufacturers had tweaked the chemicals just enough to skirt the new law.

Will actually “graduated” from his treatment program while using. Jan says the synthetic drug was so new, healthcare providers weren’t sure how best to treat those addicted. In retrospect, she believes her son should have undergone inpatient treatment. What followed was a rapid, downhill spiral.

When Will went into rehab, he lost his job at a lawn-care business because he couldn’t keep up the hours. Jan offered to pay his car insurance and commissioned paintings to keep him afloat. One was a copy of an impressionistic beach scene on the cover of American Heritage magazine. While Will hated doing “copies,” the small painting is one Jan covets because it was his last.

She says it was terrible how much the drugs changed him. She recalls Will pulling weeds out back and unable to stay on task. “His attention span was 15 seconds at most,” she says. “At that point, he was like a person with special needs.”

Will sought additional help in a ministry-based, long-term residential recovery program for men that began at the end of August 2011. But when he mentioned to a staff member he had a “partner,” Will said he detected a bias against gay men and told his parents he wouldn’t be comfortable in that setting.

The Lawrances continued to look for other options, but Will had become a shadow of his former self. When Erin looks back at the paintings Will was doing then, she can see a shift in his work. “It’s almost like you’re looking at his brain waves,” she says. “It’s like that stuff was cancer.”

Mark saw it, too. “The drugs took over his brain, melted it, and I think he just realized it was the end of the road, and he didn’t see a way out,” he says.

Around 10 p.m. on September 10, a police officer and chaplain pulled up to the Lawrances’ home. Jan, Mark, their 4-year-old grandson, and Joe were inside when they heard the knock on the door. The officer told them Will had shot and killed himself at his southside apartment. His partner found him. He hadn’t left a note. A toxicology report showed the bath salt chemicals in his blood.

Mark wailed and Jan fell to her knees, pounding her fists on the brick floor and screaming, “No!” But Joe was almost silent. He later told Erin he knew the moment when Will died. He had felt it. “But he barely mentioned it after that,” Erin says. “He felt so much hurt and pain.”

By the time they took their final family portrait, Will (left) and Joe (right) were both struggling.

AFTER WILL DIED, Mark, a triathlete, channeled his grief into cycling. He resolved to ride 10,000 miles in a year, commuting to work even in the snow and single-digit temperatures. “It was a little over the top, but just being outdoors made sense,” Mark says. It put him in a “zenlike thinking mode.”

Jan found purpose in going after those who made and sold bath salts. She pressed for tougher legislation, closing the loopholes that allowed Will and so many other Hoosiers to buy the drugs after they were banned. (Calls to the Indiana Poison Center related to bath salts jumped from four in 2010 to 356 in 2011.) Plans included testimony from Hoosiers devastated by the drugs. Jan agreed to share Will’s story, but Joe wanted no part of it. He worried some people would confuse him for his identical twin. And he didn’t want Will remembered because of his addiction. He wanted Will remembered because he was a phenomenal artist.

“My gut feeling was that he should talk about that sad part of losing Will, but for Joe, it was like a wound and pouring salt into it,” Jan says.

Not wanting to cause Joe any further pain, she worked behind the scenes with then Indiana State Sen. Jim Merritt to make the new law stronger. Merritt credits Jan with being “determined and hard-driving. We needed her,” he says. (Calls to the poison center related to bath salts fell to 26 in 2013 after the law was changed.)

Following Will’s death, Joe immersed himself in work, which included several high-profile projects at Indiana University. Among them were the renovation of the Eskenazi Museum of Art and the redesign of the university’s 18-hole championship golf course, along with a new clubhouse. Joe also sought refuge in art and travel, taking trips to Europe and South America. Enamored with the architecture of Santiago, Chile, he took pictures of all the buildings in a four-block area, creating a 15-foot-long collage mural on Mylar using his photographs and paint.

A family favorite from that period is Chicago A-to-Z, a watercolor pen-and-ink poster Joe designed for his brother-in-law’s birthday. He sketched 26 Chicago landmarks, some with playful touches. For “W,” he chose Wrigley Field, putting “Save Ferris” on the ballpark’s iconic marquee, a reference to his and Will’s favorite movie, Ferris Bueller’s Day Off. He planned to do Indianapolis A-to-Z, but only finished four sketches.

The Lawrances say Joe maintained his friendships, getting together with his old college buddies several times. He also remained close to his nieces and nephews. As Mark says, he was “doting Uncle Joe. He absolutely loved them.”

But it was hard to gauge Joe’s emotional state. On the twins’ first birthday following Will’s death, Mark and Jan struggled with how to observe the occasion. They decided against putting up the boys’ childhood birthday banner inside the house, fearing it might upset Joe. But when Joe didn’t see the banner, he insisted they put it up. He also joined his family in spreading a small scattering of Will’s ashes on the first anniversary of his brother’s death and every year after.

Whatever heartache he felt, Joe kept to himself. Jan recalls him breaking down just once. Not long after Will died, Joe was back home building a pergola for a neighbor. He was using an electric saw, so when he came to his parents’ back door screaming, “Mom!” Jan ran downstairs, thinking he had sliced off a finger. But there was no blood. He just bellowed “Will,” and fell into her arms. They held each other and sobbed.

Jan had encouraged him to talk about his brother, to share his inconsolable grief, but he wouldn’t go there, not with family nor others trying to help. As he struggled with his alcoholism and underlying mental health challenges, Joe attended some Alcoholics Anonymous meetings. The Lawrances knew Joe was drinking more, but he never did it around family. In January 2017, though, he told his parents his drinking had gotten out of hand. He needed help beyond AA meetings.

Joe initially checked into an inpatient treatment center in Indianapolis, then switched to one in Pennsylvania. But after several weeks, he decided it wasn’t a good fit and returned home, opting for a supportive-living program. He received care and counseling, but was also able to leave the premises each day to go to work. He remained sober for six months.

Looking back, Mark admires Joe’s fight, but wasn’t always sure what he was feeling. “Imagine dealing with losing your identical twin,” he says. “He tried, he really did. He was always a great family member, never a jerk. He’d go to work and do things, pretend to be a normal person, even in his final days.”

The night before he died, Joe joined Mark at Devin’s home for barbecued ribs. Nothing seemed amiss, and Joe was in great spirits. It was the same the following night, October 30, 2017, when Joe, part of a Halloween committee at work, texted Devin asking, “What’s the worst candy for your teeth?” Joe said it had to be a Charleston Chew. The two began playfully bantering back and forth.

What Devin didn’t know was that Joe was drinking heavily and in a dark place. An hour later, he shot and killed himself. The toxicology report showed Joe’s blood alcohol level was twice the legal limit.

Police found Joe alone in a budget motel on the city’s west side. The Lawrances learned he had checked in two weeks earlier after being kicked out of supportive living following a relapse. Joe didn’t tell anyone, and because of confidentiality protocols, no one from the treatment center could tell the Lawrances their son was no longer part of the program. The family later learned Joe’s counselors didn’t know he had a twin brother who had taken his own life.

THE LOSS OF one child is excruciating, a second one unimaginable. Like others who lose a loved one to suicide, Mark and Jan initially replayed the whys, what ifs, and if onlys over and over. They knew their sons were exceptionally bright and gifted, but from their late teens on, the twins had grappled with depression, anxiety, and substance abuse. After Will died, Joe was left with an enormous void nothing could fill. The Lawrances believe they did the best they could with what they knew at the time, seeking treatment and counseling while providing family support.

In retrospect, they wish there had been more continuity of care, the sharing of information among providers as their sons moved from one treatment center to another. (Too often, critical information, such as Joe’s past suicide attempts, was missing.) While the couple recognizes Joe and Will were consenting adults, the nature of their counseling and treatment confidential, they wish there was a procedure in place to let them know Joe had relapsed and was no longer in supportive living. Mark says while they’re not blaming anyone, “there is room for improvement in patient care.”

That said, the Lawrances try not to dwell on how their sons died, but how they lived and what they left behind, most notably a treasure trove of art from their childhood on, works the boys stored in closets, cabinets, an upstairs studio, and their apartments. The couple saw many pieces for the first time after their sons died. Jan compares it to finding a diary or scrapbook. “Art was how they communicated, and it’s even more powerful now,” she says. “They’re still communicating.”

Will and Joe were known as great gift-givers, and had a knack for creating a piece of art they knew the recipient would treasure. As kids, they wrapped their creations in aluminum foil and signed off with a black Sharpie. Jan cherishes her last birthday gift from Joe, a portrait of the family’s late golden retriever, Ellie. Mostly done in oil, he used a paint pen to add streaks of vibrant colors to bring the beloved dog to life on canvas.

A portrait of the family’s late golden retriever, Ellie, by Joe.

While some of the twins’ work was dark and jarring, other pieces were light and playful. They tell stories still unfolding. Mark marvels at a colorful abstract piece Will did at the Art Institute, wishing he could ask, “What are you saying with those intricate, overlapping swirls?”

When he found a painting Joe did of the Teton Mountains in Wyoming, he wondered where his son got the idea to paint a glass pane down the center with a brick wall in the foreground. During a bicycle trip in the same area after Joe died, Mark rode around hoping to find the vantage point that gave rise to the painting. He eventually found it and understood what had captivated Joe.

Beginning with Will’s death and continuing with Joe’s, the family marks the boys’ birthdays by spending the day together. It includes sprinkling their ashes at places special to them, such as Brown County and the top of Crown Hill Cemetery, a favorite vista of the twins. Mark and Jan have also spread ashes on trips to Joshua Tree National Park and other places the boys had traveled or hoped to work one day.

The family knew the first anniversary of Joe’s death would be especially hard. In the weeks leading up to it, one of Joe’s college friends gently prodded them to visit New York City. It led to a spur-of-the-moment road trip. They wanted to walk the streets Joe did, see the buildings and spaces that captured his imagination. They spent time at The Cooper Union with the dean and an archivist who showed them work Joe had done, describing what set it apart. They also met with a few of Joe’s friends, one of whom did spot-on impressions of him. He even mimicked Joe mimicking Mark, which had the family in stitches. Devin says it was great to be in a place Joe loved with people who loved him.

The first birthday following Joe’s death, the family piled into Mark’s 1964 VW Beetle with framed pictures of the twins and headed to Broad Ripple. The windows were down, the boys’ favorite music blaring. While stopped at a red light at Keystone and 62nd Street, they huddled together for a selfie, laughing as they tried to get everyone in frame. A woman in the car beside them smiled and shouted, “You’re all having so much fun!”

They nodded, smiled, and then burst into tears. The family’s grief can hit suddenly like a tsunami. It comes out of nowhere and crushes them. Jan calls it the price she pays for love. “We could focus on death, and sometimes we do, or be glad they lived as long as they did,” she says. “We have great memories.”

They hope their sons’ work inspires others. After Will died, the family established the Will Lawrance Art Legacy Fund, adding Joe’s name after his death. It awards $500 annually to three students at North Central in the categories of painting, sculpture, and photography. The recipients are chosen based on artistic talent along with character and citizenship. A recent winner in awe of the twins’ talent volunteered to photograph and catalog the boys’ vast collection on behalf of the family.

Now 67 years old, Jan and Mark have had a decade to process Will’s death and four years to consider Joe’s. Despite all they’ve been through, they describe themselves as hopeful and optimistic. They’ve continued to gain strength from their marriage of 46 years. Mark says as time goes on, he has “a more profound understanding of what’s important.” Now retired, he and Jan spend a lot of time with the grandkids and they travel more. One goal is visiting all 63 national parks. They’re closing in on 50.

Not a day goes by when the Lawrances don’t think about their sons, though. They talk openly about Joe and Will. They’re glad to see more attention focused on suicide and less stigma attached to it. Through their own experience, they know that suicide is not a disease but an event, rarely the result of a single factor. Mark and Jan continue to celebrate their sons’ lives by posting memories and pictures of paintings they come across on Facebook. “We could have shut down and kept to ourselves, but it’s been good to share,” Mark says. “They did create some amazing things.”

Erin, the twins’ oldest sister, shares her brothers’ passion for art. She rents studio space at an art center in Thorntown and participates in local art fairs. She gets goose bumps using the paint her brothers left behind. “It’s like there’s magic in the pigments,” she says. “It has helped me.” Looking back at Joe and Will’s work, Erin sees joy in the midst of heartbreak. “It’s sunny and stormy at the same time,” she says.

The boys’ other sister, Devin, a hairstylist who now lives in Indianapolis with her husband and two children, says the grief never leaves. And yet, she firmly believes “while their physical bodies are not here, their spirits are with us and they give us signs all the time.” Devin praises her parents for remaining strong in the face of so much adversity. She says their continued love has stabilized the family.

While the Lawrances will always feel the pain of losing Joe and Will, Jan prefers to focus on what they had. “No one would want to trade places with us, but I wouldn’t trade places with anyone else,” she says. “We were so blessed to have them. It’s one of those pendulums—you’re fortunate, and yet, there’s no guarantee for how long.”