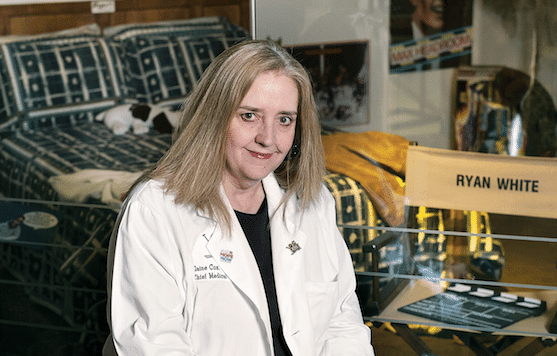

Ask Me Anything: Elaine Cox, Chief Medical Officer

You were a medical student working alongside Martin Kleiman, a pediatric infectious-disease specialist who treated Ryan White at Riley. What was it like attending to a boy who became a celebrity?

It was a circus. Elton John would stop by. The press was always parked out front. I think some people were in awe of that. Yet, for many of us, this was just a child who we cared for. The impact he had on how HIV treatment for children evolved was not foreseen by anyone.

What was the biggest challenge?

The fear of AIDS and how it impacted Ryan’s life was crippling to watch, and we couldn’t do much about it. What’s more, there were very few medications for the disease—one, actually—and the data in children was not good. For Dr. Kleiman, it was one of the first times he had faced something he couldn’t control.

You helped create the pediatric HIV and AIDS clinic at Riley and directed it for 16 years. What led you to devote your career to advocating for these children?

Dr. Kleiman told me, “We need a better clinic for kids who are suffering from HIV and AIDS, and I think you should lead it.” And I thought, Oh, OK, I’m the person who gets assigned the thing no one wants. I believed I could set it up in six months, but it took three years. There was a steep learning curve, but it was extremely fulfilling. I couldn’t part with these children.

The means of HIV transmission wasn’t well-understood when you created The clinic. Were you nervous about working with patients whom even many doctors were wary of getting close to?

I knew that the risk to a healthcare worker was negligible. But I’d get calls from people saying, “Elaine, I’ve got this baby in my practice who has just been diagnosed. Can they be in the waiting room? Should I wear gowns and gloves when I touch them?” And I was like, “You’re going to be fine.” It wasn’t malicious. It was just that information was coming from so many places. People were just trying to do the right thing.

Were your parents ever concerned you’d get sick?

I don’t remember them telling me they were worried. But they didn’t share with their friends what I did. They just told people I was a doctor.

What surprised you most about working with that population?

I came in thinking, somewhat self-righteously, that if your child has AIDS, everything you do should be devoted to making sure your child gets their medicine on time. But that’s not reality for some people. They have other children. Some had financial concerns. Some were in domestic-violence situations. Some were being discriminated against and couldn’t find a place to live. I learned very quickly that taking care of this population couldn’t just be writing scripts and ordering labs. One mom would call our office because she was having trouble helping her older son with his math homework. He wasn’t our infected patient, but we helped him anyway.

The passage of the Ryan White CARE Act ensured that anyone could get the medication they needed, regardless of income.

You saw nearly every child in Indiana affected by HIV and AIDS during your 16 years running The clinic. What other patients stand out to you?

A former patient, Paige Rawl, wrote a book about being bullied for her HIV status called Positive when she was in high school. She has since dedicated her life to supporting children who are bullied for healthcare reasons. It’s weird to read a book in which you’re a character. It was enlightening for each of us: She felt like she let me down when she was hospitalized after trying to hurt herself, but I felt like I let her down because I couldn’t protect her.

How do young patients react to a diagnosis of HIV or AIDS?

It depends when they find out. With younger children, we try to explain to them that it’s just a part of their life that they’ll have to manage, always. The older kids grieve. Their immediate reaction is, I’m never going to have a significant other. I’m never going to have a family. They think their life is completely derailed, and it takes time and effort to help them put their diagnosis into context.

At what point did AIDS change from a terminal disease to a treatable one?

Things began to change around 2010, and it was a combination of three turning points. One was when we understood that one drug at a time was not going to fight this virus. We could put them together in combinations of twos and threes to prevent the virus from mutating. I used to have patients who took 24 doses of medication a day to survive. The second was being able to measure the viral load—the amount of virus in a person’s blood—because without that, you’re just waiting to see whether people get sick to determine if a treatment’s working. And finally, the passage of the Ryan White CARE Act ensured that anyone could get the medication they needed, regardless of income. People in the United States don’t have to go without medication for HIV, which is different than in many other areas of the world.

What’s the prognosis for people diagnosed with HIV or AIDS today?

They can reach average life expectancy, which is in the 70s, assuming they have access to medication and the ability to be compliant. When we started, children didn’t live out of childhood.

What challenges does The clinic face now that the world’s attention has moved on?

When you’re the hot-button issue, people are screaming for research, for better medication, and for vaccines. But then something else comes along, and there’s not enough funding for everything. So that becomes the challenge—to keep pushing the envelope, because we haven’t eradicated it. You have to practice safe sex. You have to take your medications. We can’t let our guard down, because it’s still out there.