Vera Bradley's True Colors

Editor’s Note, March 11, 2015: Vera Bradley Designs, Inc., has announced that it will close its New Haven factory, displacing 250 workers who may transfer to other roles in the company or receive severance packages. Vera Bradley will still employ 630 workers in northeast Indiana among its 2,300 nationwide. The company had announced plans in August 2013 to expand its presence in the Fort Wayne area, adding a total of 128 new jobs by 2017, as well as tens of thousands of square footage, in the design and distribution centers there. That news arrived on the heels of 124 jobs added in 2011. Below is our June 2009 feature story on the brand.

Cathy Jansen loves her purse. She loves that it is made of lightweight cotton. She loves the print—a geometric crisscross of chartreuse, teal, and navy—and loves that this pattern has a name, Daisy Daisy, and loves the name itself. She tucks her lipstick into a Daisy Daisy cosmetics case and her cash into a Daisy Daisy wallet. Her iPod Nano slides into a Daisy Daisy tech case, and all of these pieces fit inside her Daisy Daisy tote. When she carries this purse, women she doesn’t even know compliment her. “I love your bag!” they say. And Jansen replies, “Oh, yes, it’s a Vera Bradley.”

Jansen, 48, of West Caldwell, New Jersey, loves Vera Bradley. She was introduced to the line while on vacation in 2003, when she spotted it in a gift shop. “I thought, I have to have this,” she recalls. “I’m a small-town girl, a simple Jersey girl. And Vera Bradley just reminded me of me, and reminded me of where I’m from. I thought about carrying one on the Jersey shore. It felt special, but not hoity-toity. I fell in love with them right away.”

At the time, Jansen couldn’t afford one of the handbags, but when she got home, she looked up the brand online. She read that the company was started by two Midwestern moms who still manufactured the purses in northeast Indiana. Jansen was enchanted.

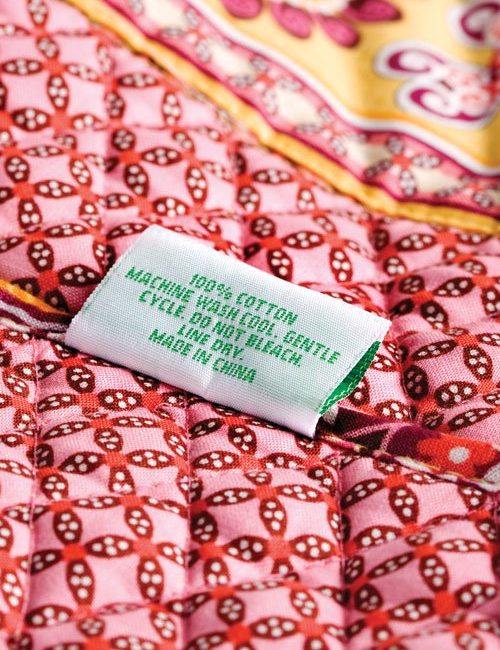

Months later, when her husband treated her to a set of Vera Bradley luggage and pocketbooks in a red-white-and-blue pattern called Americana Red, Jansen marveled at how stunning they looked piled atop a hotel cart. The first time she laundered one of the purses—part of the joy of a Vera Bradley is that you can just throw it into the washing machine—she turned over the product-care tag sewn inside. “100% cotton,” it read. “Made in U.S.A.”

Americana Red was just the beginning. Since then, Jansen has fallen for Classic Black, Peacock, Yellow Bird, and Caffe Latte. This winter, she joined a Vera Bradley fan site on the Internet, hoping to gossip with other devotees about the spring catalog. Instead, she was stunned by the online chatter. Laura, in New York, posted: “What I LOVED most about Vera Bradley products was they WERE made in the USA. Not now though. Like everything else, they are now being made in China.” And from Katherine in Ohio: “Too bad Vera has gone Chinese! Don’t think I’ll be buying them anymore. I have been communicating with corporate about my concerns. All I get back is corporate rhetoric! Used to be such a great company. What happened? And what about all those Indianans who lost their jobs?”

Jansen fetched her Caffe Latte tote and checked the tag. “100% cotton,”

it read. “Made in China.”

Vera Bradley Designs is a Fort Wayne–based producer of handbags, luggage, and other accessories, most of them made of quilted cotton in hyper-colorful, overtly feminine patterns. The brand’s popularity has soared in recent years: Between 2002 and 2007, sales revenues increased 330 percent, reaching $251 million. Today, the company’s 200,000-square-foot distribution facility can be spotted from Interstate 69, just south of Fort Wayne.

Vera Bradley debuted in 1982, just as International Harvester— which had built trucks in Fort Wayne for 60 years—was closing its plant. The manufacturer had been Fort Wayne’s largest employer, the flagship of the industrial economy of northeast Indiana. At that downtrodden time, along came Vera Bradley, building a business on floral and paisley patterns and blossoming improbably in the refuse of the Rust Belt.

Vera Bradley’s founders have been lauded as Indiana Living Legends and U.S. Small Business Administration Outstanding Woman Entrepreneurs. The company’s foundation has pledged $10 million to Indiana University breast-cancer research and endows an oncology chair at the school. Its annual outlet sale, held each spring, is Fort Wayne’s tourism season, pulling an estimated $3 million–plus into the local economy, filling area hotels with rabid Vera Bradley fans and earning a spot in local lore as the most-requested day off of the year among Allen County teachers.

Before Vera Bradley, the only fashion icon to emerge from Fort Wayne had been clothing designer Bill Blass, who left town for New York after high school and spent his career trying to distance himself from his hometown. (“Had it not been for the joylessness, colorlessness, and fatherlessness of my small-town Indiana childhood, I might not have gone anywhere,” Blass once wrote.) But unlike Blass, Vera Bradley’s marketing strategy has long relied on its Indiana beginnings. The very essence of a Vera Bradley handbag—quilted, cotton, comfortable—typifies its Midwestern roots. “We like to say that when you carry a piece of Vera Bradley,” the promotional materials once touted, “you carry a piece of Indiana!” Today, Vera Bradley winks at its home state through photos in its catalogs, which feature Indiana driver’s licenses and Indiana University student identification cards tucked into Mod Floral Blue wallets and Puccini ID holders. In the spring 2009 catalog, four members of the Zionsville High School tennis team—clad in crisp white and sporting Cupcakes Pink and Cupcakes Green bags—pose on a croquet lawn.

More than 3,700 retailers across the country, plus a few overseas, stock the purse-maker’s products, but only 26 of those are Vera Bradley stores, the full-bloom depiction of the lifestyle. At Carmel’s Vera Bradley at Clay Terrace, for instance, customers step through a rose-colored door onto honey-hued wood floors. A buttery yellow cheers the walls. Rugs in Vera Bradley’s Hope Garden pattern liven the floors. Mer-chandise is displayed in orderly but eye-popping vignettes: wristlets in Mod Floral Pink, Mediterranean White, and Rasp-berry Fizz rise in piles on a tiered plant stand; Amy purses—Night Owl against Frankly Scarlet against Purple Punch—hang from their shoulder straps on a shabby-chic-style coat rack. And along every wall, purses and backpacks and duffels are sandwiched like

library books on the shelves of chaste white hutches.

In Vera speak, these patterns are known as “colors.” The spring catalog featured 18 of them, almost all available in several varieties of cosmetics bags and luggage, plus 16 different handbags (the Audrey, Betsy, Little Betsy, Morgan, Maggie, Libby, and Gabby, for instance); six wallets (the Taxi, Pocket, Clutch, Sleek, Zip-Around, and Mini-Zip); five styles of eyeglass cases; two lunch totes; plus a checkbook cover, laptop portfolio, diaper bag, and curling-iron cover. Vera Bradley also lends its designs to makers of eyewear, home accessories, and stationery. A few times each year, the company releases new colors and retires old ones, a constant refreshing that—combined with the threat of a favorite pattern disappearing—makes fans of Vera Bradley want to not just buy it, but collect it.

“People look at these bags, and their feeling is that there is some special value inherent in the product,” says Dr. Robert K. Passikoff, a brand strategist and founder of Brand Keys, a New York–based marketing firm. “Those values resonate within the customer, and they think that they cannot get that value somewhere else. People see in Vera Bradley a sense of security, of home, of comfort.” The signature logo—oversized “V,” artsy “B,” swooping “y”—resembles the script of a favorite aunt or sister. And the oft-repeated story of Vera Bradley’s beginning—as the home-based brainchild of two baby-boomer girlfriends—personifies the dream of any stay-at-home mom who has a best friend.

In recent years, the accelerated success of Vera Bradley Designs seems to have led the company away from its mom-and-mom roots.

In recent years, though, the accelerated success of Vera Bradley Designs seems to have led the company away from its mom-and-mom roots. At first, the changes were subtle and unsurprising: A system of regional, contracted sales reps was abandoned for an in-house force, and the company began directly selling its pro-

ducts online, a move that competed with the small, independent gift shops that had helped build the business.

But the most startling decision came last year, when the purse-maker pulled its work out of five Fort Wayne–area sewing companies. The shift did not go unchallenged: Last summer, a former Vera Bradley executive who owned three of the factories sued Vera Bradley Designs, alleging that the company had committed fraud and breach of contract. So far, lawyers have been unable to reach a settlement; the case is scheduled for trial in April 2010.

Altogether, about 700 workers lost their jobs—news cushioned by Vera Bradley’s announcement that it would create nearly 500 positions at a new Fort Wayne–area production facility set to open about a year after the layoffs. The city of New Haven, a few miles southeast of Fort Wayne, gave Vera Bradley $100,000 to help fund the expansion and approved $298,000 in tax abatements, even while the federal government paid to retrain the factories’ out-of-work seamstresses in other skills.

In a year-end press release on job creation, the Indiana Economic Development Corporation touted the new Vera Bradley facility—planned for an abandoned auto-parts factory—as one of the state’s biggest success stories for 2008, even though it will employ fewer people than the factories laid off.

“We started about as simple as anyone could start,” says Patricia R. Miller, a co-founder of Vera Bradley Designs. “We had an idea and $250 from each of us.”

Miller and co-founder Barbara Bradley Baekgaard have told this story—of two neighbors who came up with an idea for pretty, feminine luggage and launched a multimillion-dollar company from the basement of a Fort Wayne home—too many times to count. Since the company’s founding, the tale has appeared on Vera Bradley product tags and marketing materials, and in hundreds of news stories about the brand’s success. It goes like this: In 1975, Baekgaard, a mother of four, had just moved from Chicago to Fort Wayne and was redecorating her home in the city’s 1920s-era Wildwood Park neighborhood. She was hanging wallpaper when her new neighbor, Pat Miller, stopped by to introduce herself. Miller, a lawyer’s wife, former schoolteacher, and mother of three, had her 5-year-old son Jay in tow.

Miller didn’t, but she was willing to learn. Soon, the pair started papering together and eventually launched a wallpapering business called Up Your Wall. “Barbara was wonderful at telling jokes; I was a good audience. She liked the doors and windows, and I liked the straight walls,” Miller says. “Anyone in business knows that you’re good partners if you each bring something different to the table but you agree, for the most part, on the result.”

After a few years, they began another business, selling clothing lines through twice-a-year home trunk shows. In 1982, just a month before their spring show, they traveled together to Florida with their families. During a layover at the Atlanta airport, they noticed that men were traveling with canvas-style carry-ons in dull colors like black, beige, and navy. And the women? They were using the same bags. “A lightbulb,” Miller says, “went on.” Wouldn’t women, the friends thought, love to travel with bags that were functional and feminine?

Back in Fort Wayne, they pooled their money (borrowing $250 from each of their husbands), hit a fabric store, and asked a seamstress friend to assemble some prototypes. The partners hoped to debut the line at their spring trunk show but needed a name that wasn’t closely associated with either of theirs. They wanted honest opinions, not sympathy sales, from their customers.

The women settled on the poetic name of Baekgaard’s mother, Vera Bradley. (Miller’s mother’s name is Wilma Polito; the choice, Miller notes, was easy.)

The women sold all of the bags and figured they were in business. But they kept operations simple: Baekgaard’s 19-year-old daughter designed the company’s first logo. Headquarters was the Ping-Pong table in Baekgaard’s basement. Their children helped fill orders while watching television but were forbidden from answering the phone during business hours. Baekgaard’s mother, Vera Bradley herself, was hired as the sales rep for South Florida.

Vera Bradley Designs filed its Indiana incorporation documents on November 15, 1982. By the end of that year, the company had grossed more than $11,000 in sales.

The earliest Vera Bradley retailers included Marshall Field’s in Chicago, but the founders mostly focused on individually owned gift shops. “We did that at first because we didn’t have the capacity to inventory,” Miller says. “And also, if

you lost a small customer, it didn’t hurt that much.”

Vera Bradley topped $1.5 million in sales in 1987. Just as the partners had complemented each other in wallpapering, they brought different strengths to the purse business. Baekgaard had an eye for design; Miller, a flair for sales and marketing. “Selling was never a problem,” Baekgaard told Indiana Business magazine in 1987, the year Vera Bradley moved into a new 26,000-square-foot building. “We had a problem producing enough of them.”

In 1988, one of the company’s first seamstresses—Kim Adams, who started off stitching the bags from the front porch of her home—began her own sewing business, KAM Manufacturing. At first, she employed 10 people in a 600-square-foot facility in Van Wert, Ohio, 40 miles southeast of Fort Wayne. But within six months, growing with Vera Bradley, Adams had run out of room and started expanding.

Yet production remained a critical problem. To address it, in 1994, Vera Bradley Designs loaned $150,000 to Fort Wayne businessman Robert Hinty and a partner to fund the launch of Phoenix Sewing, which was considered an exclusive supplier for Vera Bradley and could not offer its services to a competitor without permission from the Phoenix board. The loan agreement made Baekgaard and Miller shareholders and board members.

On April 29, 2002, Good Morning America weather reporter Tony Perkins kicked off a live broadcast from the campus of the University of North Carolina. “Before we get to the weather,” Perkins began, “we want to talk about some of the latest campus trends here at UNC. And we’ve solicited some student models to join us to show us what they’ve got.

The nation was still emerging from its post-9/11 hibernation, and Vera Bradley was a product that could satiate a desire American women didn’t even know they had. The bags were feminine, homey, wholesome, comfortable, a little old-fashioned—and American. Vera Bradley had been catching on when the sorority girl expressed her devotion; after that, it caught fire.

Vera Bradley Designs grossed $58.4 million in 2002; in 2004, it sold $93 million. Baekgaard and Miller became in-demand success stories. When Mitch Daniels was elected governor in 2004, he tapped Miller to be his commerce secretary, a post she held for the first 12 months of his term. The annual Spring Outlet Sale became so popular that in 2005 Vera Bradley ran out of merchandise and had to close the sale a day early; the next year, the company instituted a $2,500 spending cap per customer.

Yet the pressures of being the “it” bag began to chip away at the small-time nature of the company. The sales operation—a network of contractors around the country—was brought in-house. In 2004, after two decades of selling its products through small gift-shop retailers, the company began direct online sales. “We had a little bit of hesitation about it,” Miller says. “Of course some of our independent retailers were not real happy. But that is part of retail now, and I think the brand awareness helps them. They’re losing some of their sales, but some of those customers might not have gone into their stores in the first place.”

Vera Bradley also began aggressively protecting its designs, and sued Target Corp. in 2005 over a skirt similar to the bag-maker’s Sherbet color; the companies settled out of court. When Vera Bradley Designs announced plans in 2005 to build a new distribution center and corporate complex south of Fort Wayne, the Allen County Council approved $2 million worth of tax savings for the project.

The factories that made the bags also benefited from Vera Bradley’s growth. Adams’ KAM Manufacturing moved into a new 68,000-square-foot building in 2004. Hinty, of Phoenix Sewing, had joined Vera Bradley Designs in 2000 as the vice president of operations, but as demand continued to climb, he left the company in 2003 to start yet another sewing business.

The Vera Bradley juggernaut was selling handbags faster than Fort Wayne could make them. Sometime amid these boom years, Vera Bradley began reaching overseas for manufacturing help.

In November 2005, with his factories still trying to keep pace with demand, Hinty applied for a $30 million loan from Fort Wayne’s Tower Bank so that he could buy out his business partner. When the bank balked at loaning Hinty that much money, the businessman asked for support from his old friends at Vera Bradley. “Robert Hinty has been a business associate of Vera Bradley’s for the past 15 years, and I consider him a trusted friend,” Baekgaard wrote in a letter to Tower Bank on November 9, 2005. “Phoenix Sewing is a valuable component of Vera Bradley’s success, and we are committed to continuing our working and personal relationship with Bob and his company.”

Tower approved the loan. Four months later, Hinty launched a third factory. With demand continuing to increase, Hinty’s three production facilities grossed $20 million in 2006, and $21 million in 2007.

But inside Vera Bradley, changes were afoot. In October 2007, the company hired its first-ever chief executive officer, Michael C. Ray, Baekgaard’s son-in-law. “Barbara and I had been co-presidents and co-founders forever, and it was time for an evolution of the business,” Miller says. “It was just a business decision, and it was needed for the organization.”

About the time that Ray became CEO, Hinty asserts in court documents, the demand for sewing services decreased. In a series of meetings that began in January 2008, Hinty inquired about the slow workload. In March, he says, he was told that Vera Bradley was bringing sewing operations in-house.

By summer, Hinty’s three factories had closed (though one has reopened with some new business). Another factory that sewed for Vera Bradley—Superior Sample, in Rochester—also shuttered its doors and laid off its workers. KAM Manufacturing cut 140 employees.

Hinty filed suit in Allen County Superior Court in June 2008, alleging that his contracts with Vera Bradley Designs required the company to purchase his interests in his companies if Vera Bradley pulled out of the agreements, and submitting as evidence Baekgaard’s letter to Tower Bank. Vera Bradley countered that Baekgaard’s and Miller’s commitments to Hinty ended in 2002, when they sold their interests in his first factory. Additionally, Vera Bradley submitted a March 2006 contract between the purse-maker and Hinty’s sewing companies—a document Hinty did not refer to in his original complaint—and argued that it nullifies all previous agreements.

Vera Bradley Designs would not comment on the pending litigation. But in addition to the contractual dispute, Hinty’s lawsuit contains details that, if true, hint at internal struggles for the handbag-maker. According to the suit, in mid-2007 Baekgaard told Hinty that she was seeking buyers for Miller’s “minority interests” in the company, and that she wanted to retain Vera Bradley as her family business. In court documents, Vera Bradley denies these assertions.

“We’ve enjoyed reading your posts over the last few months!” the company

wrote to its thousands of Facebook friends. “Recently, we have noticed a few discussions where members have posted false information about the company. If you have questions or concerns regarding our sourcing, production, or workmanship, please see the ‘Where are Vera Bradley products made’ topic posted on the FAQ section at verabradley.com.”

Fans complained that when they followed those instructions, they found a note explaining that most Vera Bradley products are made within 90 minutes of Fort Wayne. “We like to say that when you carry a piece of Vera Bradley,” the Web site read, “you carry a piece of Indiana!”

Vera Bradley Designs will not discuss what portion of its products are made overseas. “The percentage of domestically made product versus globally made fluctuates based on customer demand,” the company spokeswoman says.

When the New Haven City Council was set to approve tax abatements for the new Vera Bradley sewing facility, Tom Lewandowski, president of the Northeast Indiana Central Labor Council, AFL-CIO, urged the board to closely consider what it was approving. “They take a bunch of jobs, they move them out of the country, and then they bring them back and harvest tax dollars,” Lewandowski says. “There are two things harvested out of what they did: tax dollars for the corporation, and press releases for the politicians.”

On New Year’s Day 2009, Vera Bradley Designs unveiled its spring line at the Rose Bowl Parade in Pasadena, California. The company’s float, entitled “Hope Grows,” featured a bountiful garden, sprouting purses in the new colors: Hope Garden, an eye-popping floral on a white background; Cupcakes Green and Cupcakes Pink, two different hues of a retro-inspired print; and Purple Punch, with a modern feel. An enormous watering can adorned with a pink breast-cancer ribbon showered the scene.

The appearance signaled the brand’s push to conquer the West Coast. Vera Bradley, with its power to remind Southern women of a Birmingham front porch and Floridians of a bright tropical day and New Englanders of a weekend in the Hamptons and Jersey girls of the Jersey shore and Midwesterners of Grandma’s quilts, has not been as popular in the western United States.

Along with the parade launch, the company produced an online video promoting the spring colors and noting its recent product-placement coups: in movies (including High School Musical 3); on TV (Desperate Housewives); in swag bags (at the Sundance Film Festival and the Tony Awards); and in magazines (O The Oprah Magazine, Teen). But the video begins where the Vera Bradley story always does—with its two founders and a basement in Fort Wayne.

It opens with Miller, sitting in a gingham chair, wearing a brown jumper, olive turtleneck, and gold hoop earrings. “We each put in $250. So we had $500 to start,” she says.

The camera cuts to Baekgaard, in a moss-green cable-knit sweater and pearls, positioned in front of a bookshelf. “We didn’t know where this was going. I mean, we’re in our basement, cutting up bags,” she says. “This was not a …”

Baekgaard pauses for the next word, opening her eyes wide and adding finger quotes around it—“business.”

Vera Bradley tag photo and Robert Hinty photo by Tony Valainis; Indiana Pacers’ Pacemates photo, Chi Omega photo, and founding mothers photo courtesy Vera Bradley

This article appeared in the June 2009 issue.