Calling for Backup

Around midnight on August 9 of last year, 15-year-old Andre Green stumbled out of the driver’s side of a red Nissan Altima, collapsing on the pavement.

Minutes before, IMPD officers had spotted the allegedly carjacked vehicle Green was driving headed east on 30th Street. Officers tailed the car. The Altima turned on Butler Avenue, careening toward a cul-de-sac. As officers gave chase, dispatch informed them that its occupants had recently fired on bystanders, peeling off four shots at a woman and her children. The officers flipped on their sirens. After trying to do a three-point turn and negotiate the cul-de-sac, the driver rammed the police cruiser, according to the IMPD, just missing an officer. Meanwhile, all of the Altima’s passengers but Green fled the car.

Officers say they demanded that Green exit the vehicle, and he ignored their instructions. Three of the cops, two of whom were white, fired on Green, who was black. “Fearing for their lives, the officers discharged their firearms, striking the driver,” according to a terse statement issued by the IMPD hours later. Medics pronounced Green dead at the scene, the youngest person killed by police in 2015.

Homicide detectives arrived to interview witnesses. The Internal Affairs Unit began an investigation. Consistent with department policy, the IMPD put the officers involved on administrative leave. “All the facts and circumstances regarding this incident will not be known for several more hours,” an IMPD statement concluded.

But months after Green’s death, the facts remained highly contested. At least one witness came forward to challenge the assertion that Green had driven the car toward police. The possibility of an unjustified police shooting sparked an angry demonstration on Monument Circle. Some wondered whether the city was teetering on the brink of its own Ferguson, Missouri, moment. “He didn’t deserve to die like that,” Green’s aunt Monica Lamb told reporters, rejecting the idea that the suspects had been firing out the car window. “You say it was a gun, but we didn’t see it.”

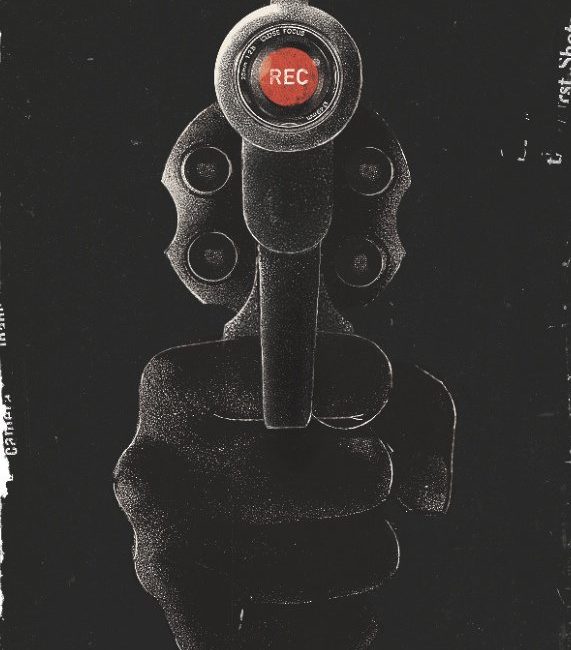

Dashcam footage didn’t exist, police said. And none of the officers involved in the incident were outfitted with one of the 65 body cameras that the IMPD had tested in a pilot program that began in December 2014 and ended in July, just days before the shooting.

Indy’s African-American community leaders began lobbying for a permanent body-camera program to hold local officers accountable. To its credit, the Indianapolis City-County Council was quick to react. By October, the council had approved $250,000 in the 2016 budget for the devices—a far cry from the $2 million it would take to outfit the entire force, but a start.

This winter, the IMPD began to equip a small percentage of its officers with the cameras. But for a short-staffed police force, every one purchased means fewer dollars available to hire the hundreds of additional officers the department says it also needs. Stories like Green’s are, unquestionably, tragedies. But given the crime wave currently flooding the city’s streets, it’s fair to ask: Are body cameras the best use of our scarce public-safety dollars?

Long before body cameras became inextricably linked with police violence in the wake of high-profile cases such as the August 2014 shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, local officials were researching the technology as a way to improve the department’s efficiency. IMPD chief Troy Riggs believes the devices could improve not only police accountability, but also capability. The phrase “body camera” is reductive given the device’s many features. The units have GPS, allowing a police department’s central office to see an officer’s location anywhere in the city. The gadgets also possess accelerometers capable of creating officer-down and officer-struggle alerts. When officers are dispatched, the camera automatically fires up. When they finish a run, the camera shuts off. The devices can even stream events back to headquarters in real time. In a hostage situation, for example, IMPD officials could watch the scene play out from miles away.

Beginning in December 2014, the IMPD decided to research the technology’s effectiveness here. The department temporarily outfitted 79 officers with body cameras and took notes on what transpired. According to Lieutenant Mark Wood, who served as former IMPD public safety director David Wantz’s chief of staff, the results were illuminating. Citizen complaints against police dropped. “Officer behavior is changing as a result of the body cameras—in a positive way,” Wood says. “We believe that citizen behavior is changing in a positive way, too. Anecdotally, officers are telling me, ‘You know, I think I’m a little more polite than I was before.’ They’re telling us that people they encounter on the streets will say, ‘Hey, is that on?’ And then everything is very cordial from that point on.”

Encouraged by their findings, IMPD officials began thinking about implementing a permanent body-camera program. But the month the trial began, former chief Rick Hite announced that the IMPD needed somewhere between 200 and 300 additional new officers to deal with rising crime. At 1.7 police officers per 1,000 residents, Indy’s force falls well below the national average of 2.5. A new officer costs about $100,000 a year, including salary, benefits, training, and standard equipment. In order to achieve the staffing levels Hite recommended, the city would have to increase the annual IMPD budget of $200 million by at least 10 percent. And that’s without adding a single body camera to the expense line.

When former mayor Greg Ballard presented his $1.1 billion 2016 budget last year, it proposed 900 body cameras, 155 new officers, and 100 vehicles. The Fraternal Order of Police supported the body cameras addition, but wanted transparency in how much the items would cost. According to Wood, for a department of 900 patrol officers, that could be between $2 million and $4 million. Sure, that only amounts to less than 2 percent of the IMPD budget, but the estimate was higher than the city council had planned. And this past September, when Indy failed to secure a large federal grant the city was counting on to implement a full program, officials had to settle for a $250,000 first phase—an amount that will outfit only about 10 percent of the force.

This winter, Andre Green’s family initiated legal proceedings against the city. In the absence of any video footage, the case will likely hinge on testimony from a few witnesses. “If there was anything capturing the incident, it would have helped his family,” says attorney Mark Sniderman, a member of the Greens’ legal team. “It could have helped the police. It could have helped everybody reach some resolution.”

IMPD officials would not comment on an active investigation and potential lawsuit, but they concede that body cameras might have prevented the community outrage. “In the Andre Green case or any other, it could provide us with multiple angles to see what happened,” says former public safety director Wantz.

According to the Green family’s notice of tort claim, evidence in the case may not support the original IMPD narrative. “At no time during the course of these events did Andre pose any reasonable threat of violence to the respondent officers,” it reads. “Nor did he do anything to justify the force used against him, and the same was deadly, excessive, unnecessary, and unlawful. Andre was not driving his car in the direction of the police officers, and did not have a handgun in his hand at the time he was shot and killed.”

To prevent another Andre Green incident, the IMPD will likely find a way to fund body cameras for every officer sometime in the coming years. Back in November, for instance, Lieutenant Wood was already working on an alternate funding plan to compete for federal grants later this year that could equip as much as 30 percent of the force with cameras. At the outset, Wantz says, they at least will be able to outfit one entire district with body cameras, and scale up from there.

In the coming months, though, the IMPD faces a competing struggle: funding the additional officers the city desperately needs to rebuild trust with a distrustful community. It’s a suspicion that was evident from the demonstrations in the aftermath of Green’s shooting. And it’s a problem the IMPD didn’t need to sift through the 4,000 hours of footage gathered during their seven-month body-camera trial to discover.

Body-camera footage in cases such as Green’s is necessary when a community instinctively doubts the official narrative surrounding police shootings. Consequently, about a third of the nation’s 18,000 police departments have already adopted the technology. Still, recognizing that police staffing levels and community trust are inextricably linked, some believe funding more officers could alleviate the immediate need for the devices. Most cities are holding off on body cameras in the near future. In November, the Madison city council voted to delay purchasing body cameras until a citizen-led panel can develop broader support in the Wisconsin community for such technology. Indianapolis mayor Joe Hogsett has discussed plans to return the IMPD to beat-level staffing, a move he says would ensure officers have time to build relationships with people in their neighborhoods—something officers have struggled to do under the department’s current officer shortage and zone approach to policing. Likewise, in another attempt to build trust, the IMPD plans to hold a series of public forums around body cameras this year.

As Wantz sees it, a full-scale body- camera program can wait. Balancing public safety and transparency is too important to get wrong. And he’s willing to bet waiting won’t bother the city or exacerbate its public-safety crisis further. “I don’t believe preventing the city from falling apart requires that,” Wantz says. “I don’t believe we are so fractured that it would require body cameras to restore that breach.”

If you ask the Greens’ attorney Sniderman, cameras will only go so far in addressing the community’s suspicions about police shootings—a distrust built over decades—anyway.

“This is no panacea,” he says.