Art of Darkness

I was reading a home-improvement magazine recently and saw an advertisement for a residential generator. It was being touted as the next must-have appliance, something no respectable household should be without. The ad warned of the perils awaiting the ungenerated—spoiled food, flooded basements, gloom of night, frostbite, heat stroke, starvation, thirst, severed communications, severed limbs, all manner of hazards. The advertisement was sponsored by the local electric company, causing me to wonder if the executives knew something I didn’t about the reliability of our power supply. It felt a bit like Wall Street peddling municipal bonds in anticipation of a stock crash.

Last fall, that same electric company came down our road, pruning back the tree limbs hanging over its wires. The company was hoping to avoid a repeat of the previous summer’s drama, when, in the midst of a tremendous thunderstorm, a tree in the Clines’ backyard fell across the line supplying the north side of town and left us without power for 22 hours. Just the month before, I had installed a battery-powered sump pump in our basement and had been eagerly anticipating some type of disaster—a blizzard, a blackout, terrorist sabotage—to test its dependability. I carried a rocking chair down to the basement to observe the sump pump sucking the water out of the sump pit and discharging it into the ditch alongside the road. Every now and then the pump would continue to run, a predicament I resolved with a sharp rap from a broom handle. Broom handles are like duct tape: There is no end to their usefulness, and no home should be without one.

A man has to think of something while sitting in his basement tending his sump pump, and I was thinking of how odd it is that in this wireless age, electricity is still delivered to our homes via roadside poles and wires, a system of transmission as treacherous as any drunken driver. In the past three years, two motorists have struck poles along our road and died as a result. This is no doubt repeated thousands of times a year the nation over, but there is no clamor to ban the poles, no Mothers Against Telephone Poles, no government agency tackling a danger that annually claims more lives than the West Nile virus and swine flu combined. If ever there were a noble cause to take on, the eradication of the telephone pole would be it.

Power interruptions are common in our area, but they are usually short-lived, and the electricity hums back on within a few minutes. When it failed to return after several hours, I went in search of the downed line and saw the truck from the power company in the alley behind the Clines’ garage. A maple tree lay over the line, the pole was snapped in half, access was blocked by an even larger maple. Ray Whitaker from the street department was there, keeping the curious public at bay, which at that moment consisted of two boys on bicycles and me. Ray can be found at the center of any town crisis, directing the rescue effort. I asked him how long the power would be off. “I’m guessing ’til this time tomorrow,” Ray said. “Got lines down all over town.”

“Three hours at the most,” said the lineman, a dreamer, it turned out, with stars in his eyes.

I informed my wife of Ray’s grim news, and she sprang into action, instituting the survival plan we devised in the event of a power loss or terrorist attack: posting a Do Not Open sign on the refrigerator and bringing up the oil lamps from the basement.

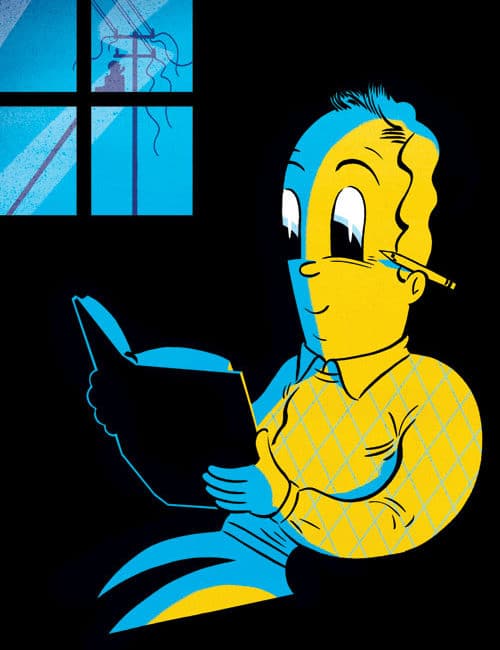

For writers, every event is grist for the mill, so I went upstairs to write about our predicament, forgetting my computer was electrified. Undaunted, I went downstairs to look for paper and pencil. The pencil, fresh from a dozen-pack, needed sharpening, but our electric sharpener sat idle, so I went to the porch to taper the pencil with my pocketknife, finishing the job with a wood file and sandpaper. It was such a satisfying task that I retrieved the other 11 pencils and spent a pleasant, aromatic hour honing them.

I thought that of all the writing utensils ever devised, the pencil had to be the finest. It is economical in cost, utterly dependable, erasable but also enduring. I once saw a mason’s penciled signature on a mortar joint, still crisp and legible after a hundred years. The pencil works in subzero temperatures, requires no electricity, is readily available around the world, makes a handy teething device for young and old alike, and can easily fit behind any ear. A man in front of a computer is generally up to no good, but a man with a pencil in his hand has a purpose, usually a constructive one—the carpenter marking a board, the teacher correcting a paper, the shopper checking a list, the editor refining an essay. The Fisher Space Pen Company spent around a million dollars inventing a pen for NASA that could do what a nickel pencil did with ease: write upside down in zero gravity.

In addition to causing me to think more deeply about pencils, not having power for 22 hours saved us a little under $2.50, our average daily cost for electricity. I was surprised we only pay that much. It seems like a pretty good deal for being able to see in the dark, preserve and cook our food, heat and cool our home, keep our basement from flooding, watch reruns of Seinfeld, and listen to Car Talk on the radio. Environmentalists tell us the true price of electricity should include the climate change wrought by coal-fired plants, but it’s almost impossible to calculate that cost, and a bit depressing, so I avoid the topic whenever possible.

Now that I have a deepened appreciation for pencils and the expense of electrical power, I’m not going to complain about them as much. If a pencil lead is cracked, causing me to make two lines when I write, I’m not going to get mad and switch to a pen, like I used to. Instead, I will go out to my workbench, put the pencil in a vise, and sandpaper the lead to a single sharp point. Nor am I going to yell at my sons anymore about leaving the bathroom lights on. At $2.50 a day, they can leave on all the lights they want. So what if our electric bill balloons to $2.70? I can afford it.

I’m also going to stop complaining about power outages. Without them, we couldn’t experience the best sensation known to humanity—the return of electricity. As the light dispels the darkness, there is no sweeter sound than the renewed hum of the refrigerator, the cool rush of air-conditioning, the radio coming on mid-song, the gurgle of the sump pump, the carbon-monoxide detector chirping its hello, the elderly neighbor down the road phoning to report that her power is back.

I always feel the need to thank someone after the electricity returns, so I go and find Ray, who, having eliminated one enemy, is already confronting another, our own Don Quixote keeping Armageddon at bay.

Illustration by Ryan Snook

This column appeared in the October 2012 issue.