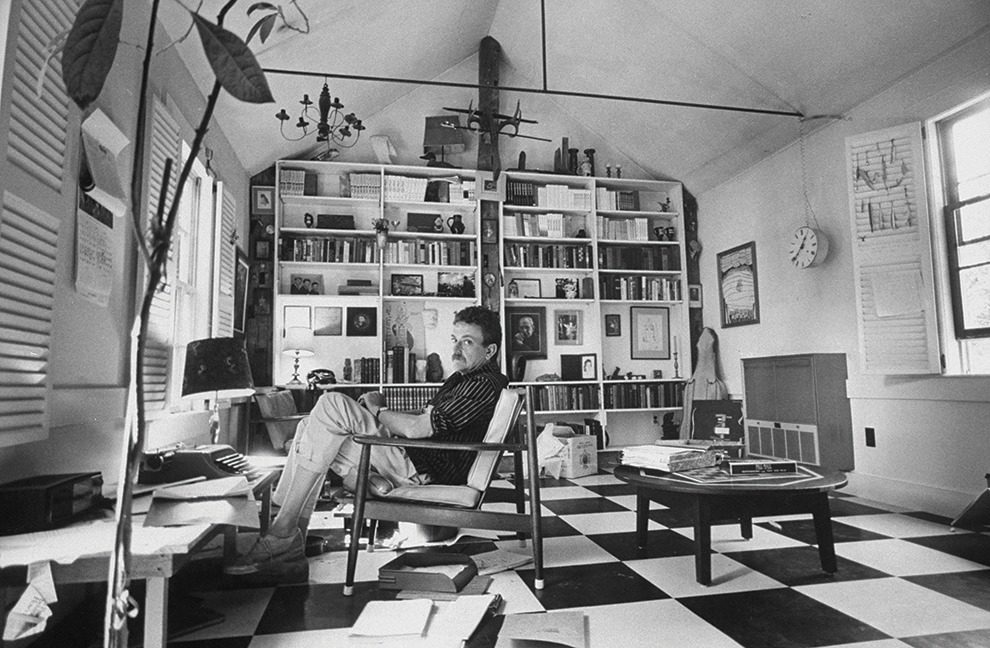

According to his friends, Kurt Vonnegut’s work on Slaughterhouse-Five in the late 1960s was a kind of therapy for the psychological trauma he had experienced as a soldier during the firebombing of Dresden during World War II. Gil Friedberg/Pix Inc./The Life Images Collection/Getty Images

Five Takes On Slaughterhouse-Five

Five Reviews: A few of Vonnegut’s fellow Hoosiers—some famous, some not—share their impressions of his most celebrated novel.

Author John GreenCourtesy Marina Waters

“The best novels change with you. Read them at 16 and they’re one kind of book; read them at 40 and they’re another. Slaughterhouse-Five first left me unstuck in time in 11th grade, when I read it while attending a boarding school in central Alabama. Back then, the book seemed so cool to me—it was clever and incisive and radically unsentimental. Now when I read it, I find one of the saddest novels I’ve ever encountered. I see a Billy Pilgrim who just wants to get home, but who must learn the terrible truth that home is not just a place but also a time—one to which you cannot return.” —John Green, author of Turtles All the Way Down and The Fault in Our Stars

Mayor Joe HogsettCourtesy Indy.gov

“Indianapolis wasn’t always eager to associate with Vonnegut. Once upon a time, many in our city found him vulgar, obscene, and weird. Young people, though, always got him. And the young people of 1969 are the leaders of today. Additionally, one thing I think we can say—and which Indianapolis sons like Vonnegut prove—is that we have a rich sense of humor in this city. Even when criticism comes my way, I can (usually) laugh at the caustic, smart-alecky tone. So while Slaughterhouse-Five isn’t one of Vonnegut’s most Indy-centric books, it is a book with a perspective on life that could come from no other city.” —Joe Hogsett, mayor of Indianapolis

Julia Whitehead

“Vonnegut survived a firebombing and POW camp. Lucky son-of-a-gun. Then again, maybe he wasn’t so lucky: his mother’s suicide, the Nazis, the nightmares, the struggle to create something from it. After 20 years of trying came his cathartic war story. Some readers love Planet Tralfamadore. Some love the time travel with Billy Pilgrim. Others love the humor, the absurdity. But I love the Vonnegut in Slaughterhouse-Five. I love the soldier, the man who shares himself. Some hate the vulgarity and profanity, but war is vulgar and profane. Some think the sexy character Montana Wildhack is inappropriate. But don’t we all need to escape to beauty in our minds sometimes? Don’t we all need Vonnegut’s wake-up call?” —Julia Whitehead, CEO of the Kurt Vonnegut Museum and Library

Author Deborah Kennedy

“Once, on the phone in the middle of the night, my friend Mark and I came up with the idea for a Kurt-inspired theme park called ‘Vonnegutopia.’ Mark, a self-deprecating but brilliant songwriter and Vonnegut junkie, suggested we name one of the attractions ‘Troutland’ for Kilgore, and another ‘Valencia’s Wild Ride.’ The latter would allow passengers to drive recklessly to a hospital where they would die promptly of carbon monoxide poisoning. And ‘Slaughterhouse-Five, The Experience’ would give ticket-holders the chance to punch a cow carcass, Rocky-style. It was a slap-happy, vodka-fueled conversation that I had forgotten about until a few months later when a friend told me that Mark had killed himself after a long battle with depression. Mark’s death has me wishing that Vonnegut’s Tralfamadorians were not only real but right, because according to those wise, toilet plunger–shaped creatures, my friend is still alive somewhere in time.” —Deborah Kennedy, author of Tornado Weather and 2018 Indiana Authors Award winner

El’ad Nichols-KaufmanCourtesy El’ad Nichols-Kaufman

“Many essays have been written about Slaughterhouse-Five, most of them by literary professors. Few have been written by people in Kurt Vonnegut’s position just before the war—that is, someone who had only recently graduated high school. I’m a student at Shortridge, the same school Vonnegut attended 80 years ago. Although many things have changed since Vonnegut roamed these halls, one thing has not: the path from high school to military. Slaughterhouse-Five is very much about a war fought by children, for reasons beyond them. Wars today are no different. We’re fed stories about war that encourage us to go out and fight, but when some of us reach the battlefield, we discover that the value of a life there is insignificant. This is the power of Slaughterhouse-Five to me. It speaks to the struggles undertaken by children.” —El’ad Nichols-Kaufman, reporter at The Shortridge Daily Echo