Carmel’s Shortage of Low-Income Housing is About to Get Worse

At first glance, Kathleen Calhoun appears to be exactly the kind of citizen Carmel officials call the future of the city. The hardworking 34-year-old editor, who has a bachelor’s degree from Kansas State University, aspires eventually to earn her M.F.A.

But today she can barely afford to live in the gilded suburb, despite working 35 hours a week at a Starbucks there, driving for Uber on the weekends, and taking contract editing jobs. Calhoun earns about $940 per month—just $5 more than her monthly rent at Gramercy Apartments a few minutes from her day job. With $46,000 in student loans, not to mention basic necessities to cover, Calhoun’s only financial backstop is splitting the cost of rent with her mother, with whom she’s been living since 2007.

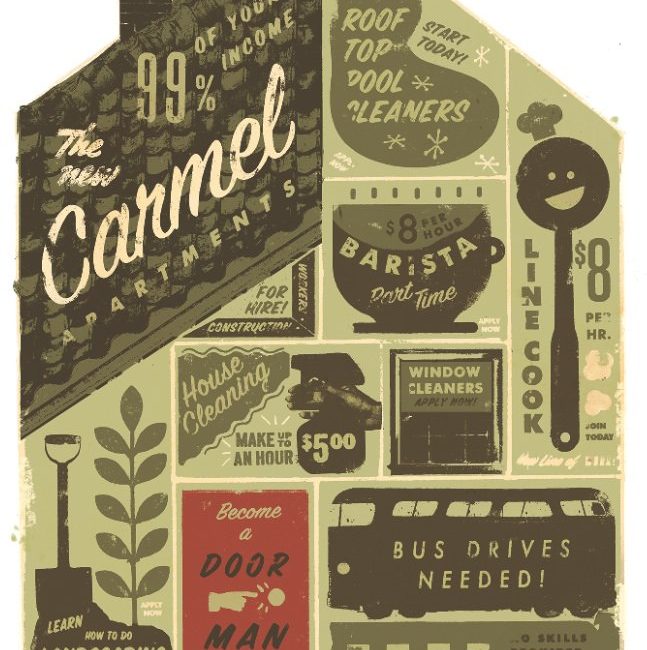

“The people in our apartments work for the people who can afford to own homes here,” Calhoun says, referring to her bank-teller and retail-worker neighbors in Gramercy, one of the lower-cost multi-family developments in Carmel. “We can’t afford to live here.”

Like Calhoun, thousands of Carmel’s service workers struggle to find affordable housing. Not far from the Palladium’s limestone facade or the gleaming $300 million City Center, almost 3,000 of them currently live in poverty—and countless more have to commute from far-flung places in Indianapolis, from which there isn’t great public transportation. The housing crunch comes as hundreds of millions of dollars of new development splashes across the suburb, from grocery stores such as the $100 million Giant Eagle Market District to the upcoming $60 million Proscenium on Range Line Road. With demand for such projects spiking, city officials and developers continue to shun low-income housing projects, which promise thinner profit margins and fewer tax receipts.

All of which raises the question: As Carmel strives to attract the young and upwardly mobile to its tony neighborhoods and mixed-use developments, where are the working-class people employed in the businesses that serve them going to live?

Of all places, Carmel is home to the company that essentially invented modern low-income housing. In the mid-1980s, when Bruce Cordingley worked as an attorney in the real-estate division of Ice Miller, congress was debating the Tax Reform Act of 1986. Cordingley and Dennis West, then the president of a local real-estate group, read through the House version of the act. They enumerated several problems they saw in a letter to Senator Richard Lugar, then the senior member of the finance committee. Lugar lobbied for a provision Cordingley and West both wanted: the Low Income Housing Tax Credit program. It passed. Through tax breaks, LIHTC encouraged developers to build apartment buildings with a certain number of units set aside for poorer renters who could occupy them at a discounted rate. That kind of development came to be known as Section 42 housing.

Seeing a business opportunity, Cordingley founded Pedcor the following year, and developed the first Section 42 rental housing project in Central Indiana shortly thereafter. When Cordingley was getting started, Carmel zoning laws only allowed apartment buildings with 12 units or fewer. As a result, when five-term mayor Jim Brainard took Carmel’s top office in 1996, the community’s housing stock was about as diverse as its overwhelmingly white population—a lot of single-family homes occupied by the owners, and little else. Early on, as Brainard tells the story today, he spent some political capital to change that. “There hadn’t been any apartments built in 10 or 15 years,” he says. “You can’t have a city with just one kind of demographic.”

Under Brainard’s watch, the housing landscape slowly changed. Sprawling apartment complexes—most of them featuring top-shelf amenities such as hot tubs and virtual golf simulators—sprang up, with rents ranging from $700 to more than $2,000. But Pedcor doesn’t have a single Section 42 building in its own backyard; the closest such development is GreyStone in Noblesville. Pedcor’s Carmel properties are market-rent marquee projects, including City Center, the Indiana Design Center, and Old Town Shops. Cordingley claims Carmel just isn’t an enticing sandbox for Section 42 developers because it lacks a supply of cheap property. “Who’s going to pay the excess land price?” he says.

But at least one person has suggested that something more sinister is behind the lack of affordable housing. After all, low-wage workers don’t exactly bring in a lot of tax revenue. John Accetturo, a former Carmel city councilman whose term ended in 2012 and who challenged Brainard in the 2011 primary, claims the shortage is the result of a deliberate attempt to shut the poor out. “I believe there is a push to keep low-income people from living in Carmel by the Brainard city council,” he says.

Outside Roper Capstone, a historic building in downtown Noblesville, Nate Lichti fumbles with his keys. The executive director of Hamilton County Area Neighborhood Development (HAND), Lichti leads an organization that develops low-income housing in the area. Roper Capstone, a century-old, long-vacant structure at the corner of 8th and Division streets, is HAND’s latest project. Once inside, Lichti gives a tour of six cozy one-bedroom units with kitchens, washers and dryers, and exposed ductwork. The $1 million project is the third building on the block HAND has renovated thanks to funding from the Indiana Housing and Community Development Authority and the Federal Home Loan Bank of Indianapolis.

Why is a ribbon cutting on a property like this happening in Noblesville and not Carmel? The answer, Lichti says, is more complicated than high land prices or a council that allegedly wants to keep out the poor. A byzantine scoring system used by the housing authority to approve affordable projects favors older, more urban sections of the state, as opposed to newer Carmel. For the past five years, most tax credits for such developments have been issued for adaptive reuse: taking an old building like Roper Capstone and converting it to affordable housing units. Those are not in abundance in Brainard’s neck of the woods.

While that scoring system has changed somewhat thanks to the efforts of groups such as HAND, it hasn’t altered enough yet to make a meaningful difference. Lichti says that Hamilton County requires dozens—if not hundreds—more developments to keep pace with the area’s need for affordable housing. At present, HAND maintains a waiting list of 200 individuals interested in Section 42 somewhere near Carmel. “If we don’t produce some housing for this community, we’re really going to restrict the mobility for this group of folks, the economic opportunities for the businesses, and the richness that comes with diversity,” Lichti says.

According to him, 10 percent of all new residential developments in Hamilton County need to be designated for affordable housing to meet the demand. That’s about 350 new units a year. At present, the rate falls somewhere around 2 percent, leaving a substantial gap. “We need local officials to buy in and make it happen,” Lichti says. “But there’s just not a lot of sympathy for lower-wage workers.”

Sitting in a conference room decorated with a glossy rendering of Midtown—a new $45 million development in Carmel featuring condominiums, a rooftop pool, and a sky bridge—Brainard bristles when asked about the lack of affordable housing in his town. “I would argue that we have a lot of it,” he says. “When I came in as mayor, we had very few apartments here. Today, you can get one in Carmel for $500 or $600. You can afford that on a fast-food income if you have to. We’re one of the few places in the country that has affordable housing provided by the private sector.”

Pressed further, though, he admits that those apartments—Pedcor’s GreyStone—are actually in nearby Noblesville. In 2013, Brainard discussed the idea of putting in some low-income housing in Midtown. But council members balked, suggesting that such plans would not stimulate the city’s economy. “It wasn’t much more than a discussion, and there were some on the previous council who were hesitant and others more interested,” Brainard says. “Due to the recession, the project didn’t develop enough for there to be a concrete proposal.”

Brainard points to condo prices elsewhere in the city starting as low as $75,000, and he has proven at times to be sincere in his quest for more diverse housing. When Herman & Kittle Properties set its sights on the former home of the Glass Chimney restaurant in 2014, hoping to turn it into a 40-unit affordable apartment community for the elderly, Brainard backed the development. But the developer’s application for financing with the Indiana Housing and Community Development Authority wasn’t green-lit due to the state’s scoring system for such projects. Today, the property is home to a Bru Burger Bar.

As Carmel’s population grows and the city’s economy becomes more service-based, its need for affordable housing will only increase. Some 23 percent of the jobs in Hamilton County now are considered low-wage, according to a recent study. That’s a 22 percent increase in the five-year period from 2010 to 2015. In the next five, count on hearing from a lot more workers such as Calhoun, the editor and barista. She says she’s considering leaving the suburb for a job teaching in South Korea, where her housing would be subsidized and her salary would increase. From her perspective, Carmel just isn’t for people like her. “You want your latte,” Calhoun says. “You want your dry cleaning in 24 hours. If you want to keep service workers for these things, they have to be able to live here.”