The Terre Haute Experiment

One day in February 2007, Rachel Meeropol stumbled upon a news story about a “secretive” and perhaps illegal prison unit “isolating Muslim, Middle Eastern prisoners,” which had sprung up like newly planted corn on the plains of southwestern Indiana, in Terre Haute. The RawStory.com article, written by journalist Jennifer Van Bergen, piqued Meeropol’s interest.

For the last five years, Meeropol, a New York human rights attorney who worked for the Center for Constitutional Rights, had helmed similar cases.

Meeropol was the kind of lawyer who had made her bones by picking clean those of the U.S. government. At that point, her biggest case had been Turkmen v. Ashcroft, a civil rights lawsuit the Wesleyan University and NYU law school grad filed in her first year at the nonprofit. The case was a class action filed against top Bush administration officials in the wake of the sprawling search for the perpetrators of 9/11, one that had rounded up scores of Muslim and Arab immigrants as terrorism suspects, subjecting them to beatings and solitary confinement in detention centers. Meeropol won the case on appeal, arguing the matter all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court. (The case has since changed to Ziglar v. Abbasi, she argued it in front of the high court earlier this year, and a decision is pending.) In fact, she literally wrote the book many prisoners use to learn the ropes of the legal system while behind bars: The Jailhouse Lawyer’s Handbook.

In her unkempt seventh-floor office at 666 Broadway in Manhattan, Meeropol began scouring the internet for any details she could find about the Terre Haute prison division, called a Communications Management Unit, or CMU. As she worked, she would occasionally glance at a poster above her desk. It was from a charity event she attended in 2003 for the Rosenberg Fund for Children. “A program to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the execution of Ethel and Julius Rosenberg, and to celebrate today’s families for social justice,” it read. Whenever she looked at the poster, she thought of her infamous grandparents, the Rosenbergs—a pair of suspected Russian spies who allegedly leaked details of America’s atomic bomb to the Soviets during the Red Scare of the 1940s. The Rosenbergs maintained their innocence, but the U.S. government convicted the couple of conspiracy to commit espionage in 1951 and executed them by electric chair in 1953. Even today, details of the case remain hotly debated.

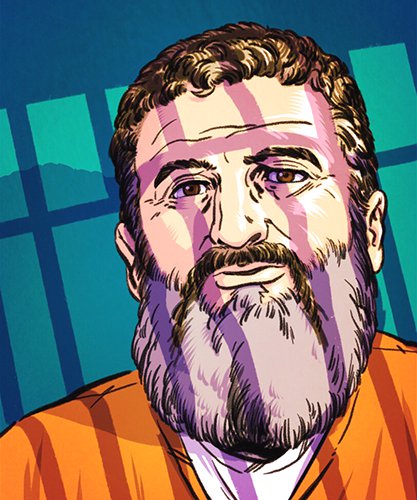

Meeropol’s online sleuthing led her to a letter one of the prisoners had posted weeks earlier. It was written by Rafil Dhafir, a former New York oncologist. Dhafir had been swept up in a controversial 2003 counterterrorism operation for supporting of an Iraqi children’s charity, on the grounds it violated economic sanctions against Iraq at the time. Dhafir, the letter said, had arrived in December 2006 at the Terre Haute Federal Correctional Institution with 16 other prisoners, the majority of them Muslim or Arab. Dhafir wrote that the guards said their confinement was an “experiment,” one he described in his letter as reminiscent of the novel 1984. The inmates had taken to calling the place Guantánamo North.

Meeropol began corresponding with Dhafir and several other inmates she found. It seemed to her that this prison within a prison was designed to segregate Muslims. Inside D-Unit, word got out that a New York City attorney was thinking of taking on the inmates’ case against the government. In the coming months, letters from more inmates within the unit poured into her office. As far as she could tell, Meeropol had a solid case on her hands. But she couldn’t prove anything without first forcing the federal government into the discovery process. She needed to figure out what conditions were like inside the prison.

So began what has been a seven-year case for Meeropol, one that is expected to be decided later this year. It’s a legal battle royale that has taken on greater significance in the current climate of increasing Islamophobia. As Meeropol sees it, what happens inside the walls at the Terre Haute prison in the coming months could be a harbinger for the state of civil rights outside of its walls. Entering its tenth year in operation—and its third presidential administration—Guantánamo North faces an uncertain future. But there’s at least one thing about which Meeropol is certain: “It’s the United States’ first political prison.”

On the morning of February 26, 2003—weeks before the U.S. invasion of Iraq—Dhafir had walked out of his house, taken out the trash, gotten into his Lexus, and headed to his practice when a little after 6 a.m., he was arrested. Elsewhere, some 150 predominantly Muslim families who had also donated to the controversial Iraqi charity were interrogated.

Dhafir eventually landed at Flatiron Federal Correctional Institution in New Jersey, but three years into his incarceration there found himself again facing an abrupt turn of events. At 7 a.m. on December 11, 2006, he had awoken to news that he was being transferred. Guards told him he would be escorted to a bus under the watchful eyes of “riot police with full gear and machine guns.”

The cloak-and-dagger development perplexed Dhafir. He had no history as a violent offender. He had maintained a clean sheet as an inmate at the medium-security prison. Before serving time, Dhafir had presided as an imam—a mosque’s volunteer prayer leader—at the Islamic Society of Central New York. He had practiced medicine in the upstate town of Rome, New York, for nearly three decades.

Still, he was “whisked” away from his cell, then put on a bus, in shackles, hurtling to an unknown location and unknown fate. The bus traveled to Fort Dix, an Army base near Trenton. There, it picked up another inmate. Next, it stopped at a prison in Lewisburg, Pennsylvania, where Dhafir was joined by seven more detainees. Twenty hours later, his body aching, Dhafir arrived in Terre Haute and was placed in what he would later describe as a “dungeon” for two days.

He slowly adjusted to life in the self-contained unit, which featured a dining area, a television lounge, and exercise equipment. He made progress in understanding his current state of affairs. Like Dhafir, two-thirds of those in the unit were Muslim, even though nationwide, only 6 percent of the population of U.S. prisons observe the faith. They were situated inside a separate wing of the prison called D-Unit, the former home of the prison’s death row. It was the same block where the Oklahoma City bomber, Timothy McVeigh, languished before he was executed in the summer of 2001. They were tucked in inside one the prison’s V-shaped wings, made up of 55 cells. (Prison officials decline to confirm where the unit is, but inmates and lawyers who have visited say this is the location.)

The idea for the units appears to have originated sometime after March 2005. That month, officials from the Federal Bureau of Prison, or BOP, had come under fire when a letter from one of the incarcerated terrorists behind the 1993 World Trade Center bombing was intercepted by Spanish intelligence officers and forwarded to the CIA. The letter, written by the bomber Mohamed Salameh to a Spanish terror cell, encouraged them to “rise up against American arrogance and tyranny.” U.S. Senator Chuck Schumer, a New York Democrat, fumed to NBC News: “Those who allowed this lapse to take place should really be fired from the Bureau of Prisons.” The Republican Attorney General at the time, Alberto Gonzales, promised an investigation.

At some point in 2006, perhaps as a response to that incident, officials quietly redesignated a section of Terre Haute’s prison to warehouse a new kind of inmate under circumstances unlike those at any other U.S. prison at the time. The group, isolated from the general population, would get only one 15-minute call a week, 60 minutes a month. That compared to 300 minutes a month for other inmates. They were to speak English on the phone. Visits were to include no physical contact—not even a brief embrace with a relative at the end—and also had to be conducted in English. Calls, mail, and visits would be monitored remotely by FBI intelligence analysts at the Counter Terrorism Unit in Martinsburg, West Virginia.

(In 2008, the feds opened up a second CMU, about 177 miles away in Marion, Illinois. There, roughly 72 percent of prisoners were Muslim. In total, the two units held between 60 and 70 prisoners.)

Months after Dhafir and other inmates arrived here, relations between the guards and prisoners of D-Unit began to unravel. There were tense meetings between the warden and the inmates. At one meeting, documented in a March 15, 2008, letter by Dhafir, a prisoner complained of receiving underwear with feces in them. Windows in the dining area were blacked out, making it hard to track the days and nights of their confinement. An FBI agent lingered among the prisoners, which incited fear of possible entrapment. But perhaps the most offensive restriction, as the prisoners saw it, was that the group prayer they had enjoyed for the first six months was abolished. They could only pray together once a week or on special holidays such as Ramadan. Ken Falk, an attorney with the American Civil Liberties Union of Indiana, represented John Walker Lindh—the so-called “American Taliban” also housed in D-Unit—in a lawsuit against the BOP. Indianapolis U.S. District Court Judge Jane Magnus-Stinson ruled that the restriction violated the 1993 federal Religious Freedom Restoration Act. Even after her ruling, though, the prayers only increased to three times a day, despite the fact that religious custom dictated five. Falk filed another motion. Magnus-Stinson found the federal agency in contempt. The warden was forced to permit the additional group prayer sessions.

Meanwhile, Meeropol and a team of lawyers spent the next year corresponding with, and later visiting, inmates at Terre Haute. During the summer of 2007, Steve Downs, one of the lawyers working with Meeropol on the case, made a trip to Terre Haute. He was there to see Yassin Aref, an inmate who Meeropol had corresponded with early on. Working past a routinely icy prison guard nicknamed “Miss Fortune,” Downs met with Aref and his children. At one point during the meeting, Downs began scrawling notes on his legal pad. The guard interrupted him. He had agreed not to bring in any “recording equipment,” and even though he was an attorney, a pen struck the guard as “recording equipment.” Miss Fortune terminated the visit.

Undaunted, Meeropol and her team had gathered enough to bring the case to court that spring. On April 1, 2010, seven plaintiffs filed a lawsuit against the BOP on the grounds that the terms and nature of their confinement violated not only their due process rights, but also the Eighth Amendment, which bars cruel and unusual punishment. The civil complaint—against former Attorney General Eric Holder, Director of the Federal Bureau of Prisons Harley Lappin, and D. Scott Dodrill, one of Lappin’s deputies—alleged that the BOP “secretly created two experimental prison units designed to isolate certain prisoners from the rest of the BOP and the outside world … A ban on physical contact for this lengthy period, for no legitimate penological purpose, is cruel and unusual …”

Two years before prison officials redesignated Terre Haute’s D-Unit in 2006, the engineering company Kellogg Brown & Root had finished constructing a Cuban detainment facility that bore a striking resemblance. KBR, the former subsidiary of the multinational corporation Halliburton, opened the cells of Camp 5, one of several detention camps at the infamous Guantánamo Bay Naval Base. Like its northern simulacrum, the Guantánamo prison featured two-story wings, 12-by-8-foot cells, and a caged recreational area. As one of the nation’s highest-security prisons, Terre Haute’s layout, with cells around a common area, offered an ideal floor plan for the kind of high-value detainees housed there. To be certain, conditions at Guantánamo North are believed to be worlds better than those of its southern cousin. Unlike the CIA black-site prison in Cuba, the cases of inmates at Terre Haute have wended their way through the court system. There have been no allegations of the kind of severe psychological and physical terror in Terre Haute that occurred at the detainment center in Cuba. Still, Falk, the ACLU attorney, one of the only outsiders to have visited the prison, says the surveillance is unlike anything he’s ever witnessed. “It’s oppressive,” he says of the Terre Haute unit. The physical conditions, though, are not. “I don’t want to make it sound like it’s the kind of place everyone would go to, but I do not think that the actual conditions of confinement are the problem. What might be a problem is, why are these certain prisoners confined there? Why aren’t they allowed to be in the general population?”

The Indiana prison wasn’t always an object of international intrigue. When it opened in 1940, the Terre Haute Federal Penitentiary promised to be a new kind of correctional facility. Not long after President Franklin Roosevelt rubber-stamped its construction as a make-work project in June 1938, justice advocates hailed it as a monument to progressive ideals. Men here would not be called criminals, but inmates. “Prisoners were identified by names and not numbers, custodial officers supplanted guards, cells became known as quarters, and imposed silence at meals gave way to conversation,” according to an account in the Terre Haute Tribune Star. It would also be among the first facilities of its kind to offer inmates the chance to learn a trade while incarcerated. E.B. Swopes, the prison’s first warden, marveled at its open structure, more welcoming than its predecessors: “There are, for instance, no massive interior steel cell blocks of the type which has characterized practically all American prisons since the old cell block,” he told the newspaper.

Some 90,000 citizens swarmed an open house after it was built. Literature published by the BOP sold the facility as a boon to the community that would offer well-paying jobs. “No desperate criminals or hardened offenders will be committed to Terre Haute,” the booklet read. “It is to be used to house only those adult offenders who are not criminal on a habitual level and who have not committed serious crimes of violence.”

At the $3 million prison’s ribbon cutting ceremony, the president of the BOP, James V. Bennett, called the institution “one of the symbols of the American way of life.” It was, he added, “built around the idea that each human life is sacred and that even those who have sinned against the social order are entitled to a fair trial, fair treatment, and fair attention to their problems and troubles.”

“Men,” he said, “are sent to prison as punishment and not for punishment.”

Rachel Meeropol, the grandchild of alleged spies perhaps wrongly executed by the U.S., has led the legal charge against Terre Haute’s “Gitmo North.”

If anyone knew how to fight the federal government, it was Meeropol. Hours before her grandparents’ execution, the Rosenbergs wrote a letter to their sons, Michael, 10, and Robert, 6. “Your lives must teach you, too, that good cannot really flourish in the midst of evil,” wrote Ethel, “that freedom and all the things that go to make up a truly satisfying and worthwhile life, must sometimes be purchased very dearly.” Working with prisoners, Meeropol learned that lesson on her own. “I grew up with the understanding that government power could be wielded in an incredibly destructive way,” she says.

Fueled by this congenital distrust of the feds, the five-figure lawyer working six-figure hours knew how to get results. For one, she forced the BOP into a discovery process, casting light for the first time on conditions inside the prison, along with the stories of the inmates who were housed there. In a matter of days after Meeropol filed her suit, the BOP responded by opening up a period of public comment, standard operating procedure before opening a unit, not after. Meeropol and her team solicited critical testimony, including prisoners and their family members, generating 700 comments, most of them negative. “[T]hese units are not only an affront to civil liberties, they defy what it means to be human,” wrote one inmate’s loved one. “They strip human beings of their chances for human connection, to be close to the people they love. They destroy families. They destroy people.” According to comments from three former correctional officers—Raul S. Banasco, Steve J. Martin, and Ron McAndrew—along with the Brennan Center for Justice at the New York University School of Law, the units “make prisons more dangerous, increase recidivism, and harm inmates and their families.” The feedback was welcome progress in the case, though short-lived.

That July, the government filed to dismiss the case. Meeropol pushed back. The court mostly sided with her, agreeing that the prisoners had a case. As the matter languished, Congress became involved. The following October, 11 members of Congress wrote to the BOP’s acting director, Thomas R. Kane, demanding more information about the creation of the CMUs, inquiring why such a disproportionate number were Muslims. They also questioned the conditions of their captivity. “Given what the research tells us about the importance of family and community to successful re-entry and rehabilitation, the isolation experienced by prisoners in situations such as the CMUs, and the ways in which they are prevented from maintaining their family ties, is counterproductive. If CMU inmate communication is being closely monitored, why are CMU prisoners not allowed to receive contact visits?” To be certain, other prisons throughout the federal system employ variations of the CMUs’ no-contact policy. As Meeropol’s team argued, though, “the blanket ban on physical contact during visits is not unique within the federal prison system,” but it is uniquely harmful.”

Once again, in March 2014, the BOP invited public comments on the controversial units, ahead of issuing a formal policy pronouncement. This time, Meeropol and her team submitted more than 400 comments objecting to the units. It seemed to make no dent in the agency’s case for places like D-Units. By February 2015, the BOP issued a final rule supporting the existence of the CMUs. The agency argued that the “ability to monitor such communication is necessary to ensure the safety, security, and orderly operation of correctional facilities, and protection of the public.” Likewise, the units shouldn’t “discriminate against inmates on the basis of race, religion, national origin, sex, disability, or political belief.” Finally, the document argued, “the presence of Muslim inmates in CMUs does not indicate discrimination.”

In a March 16, 2015, opinion, U.S. District Court Judge Barbara J. Rothenstein ruled that the plaintiffs “failed to establish that designation to the CMU is an ‘atypical and significant hardship … in relation to the ordinary incidents of prison life.’”

Meeropol and CCR appealed the decision that October. Despite the setbacks, Meeropol had forced the government into the discovery process, as well as winning her clients slightly better CMU conditions, including more phone and visitation time. “To the extent that there have been improvements, those could be lost when the Bureau of Prisons is no longer in litigation on the issue,” Meeropol says. “That’s why we think it’s important that the court orders those robust due process protections be put in place prior to transfers. If there’s no protection, the government could just use this as a political prison.”

Sitting in a booth at David’s 63 Cafe or idling in the parking lot of a lonely Dollar General is as close as most people will get to Terre Haute’s Guantánamo North. Details about the future of D-Unit, as well as its current inmates, remain as murky as the coffee at David’s. In response to a request seeking those answers and even more basic ones, Tovia Knight, a public-affairs specialist with the BOP, wrote: “The number of inmates in the CMU at USP Terre Haute is not public information; therefore, that information will not be disclosed. FCC Terre Haute’s ability to manage multiple missions was considered in the decision to implement the CMU. The Bureau declines to comment or speculate about the future use of CMUs.”

Last August, the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals ruled in favor of Meeropol’s case against the CMUs. She wrote in a statement: “Today’s ruling ensures that a court will finally rule on the previously secret information we disclosed through this lawsuit, documents that show a pattern of discrimination and retaliation in CMU placements made possible by systemic due process violations. The court’s decision makes clear that the BOP cannot simply send anyone they want to a CMU, for any reason, without explanation, for years on end.”

A final decision on whether the CMUs violate inmates’ due process is expected later this year. The court could order Meeropol and the BOP to work together to develop procedures that are constitutional. Or, it could rule that the BOP alone should develop these procedures. Until then, Meeropol remains worried that the government could use CMUs as political prisons. “It could use this as a place to put people whose political opinions they don’t like, whose speech they don’t like, and whose faith they don’t like,” she says.

Maybe that’s why the debate around Guantánamo North and its ilk remains an abstraction, and hasn’t garnered the headlines or the interest of crusading politicians. But the issue is on the radar of some Islamic advocates. Ibrahim Hooper, a spokesman for the Council on American-Islamic Relations, a Washington, D.C.-based nonprofit, said his organization has opposed the units from the start, due to the disproportionate share of Muslims they house. He is monitoring any possible policy change under the Trump administration. “I don’t want to give him any ideas,” he says.

If, as one guard told Dhafir, the units are an “experiment,” the only evidence to support their existence is a negative. And how do you disprove a negative? In the case of Terre Haute, there has been no evidence that the lack of physical contact and close monitoring of letters have made the nation safer. Real experiments have end dates and results.

For now, the test in Terre Haute continues, 10 years after Rafil Dhafir transferred to the D-Unit there. In emails sent from a less restrictive facility in Devins, Massachusetts, where he was transferred thanks to Meeropol’s work, Dhafir, now 68, says he walks 3 miles every day and spends time reading and praying. “CMUs are nothing but abuse of power and serve nothing,” Dhafir wrote, five years left in his sentence. He went on to explain that another fellow former “victim” recently arrived at Devins. Dhafir is wary of him. “Don’t know if he is a spy for them or a real person.”