Why The Coronavirus Could Widen The Gap Between Indy’s Neighborhoods

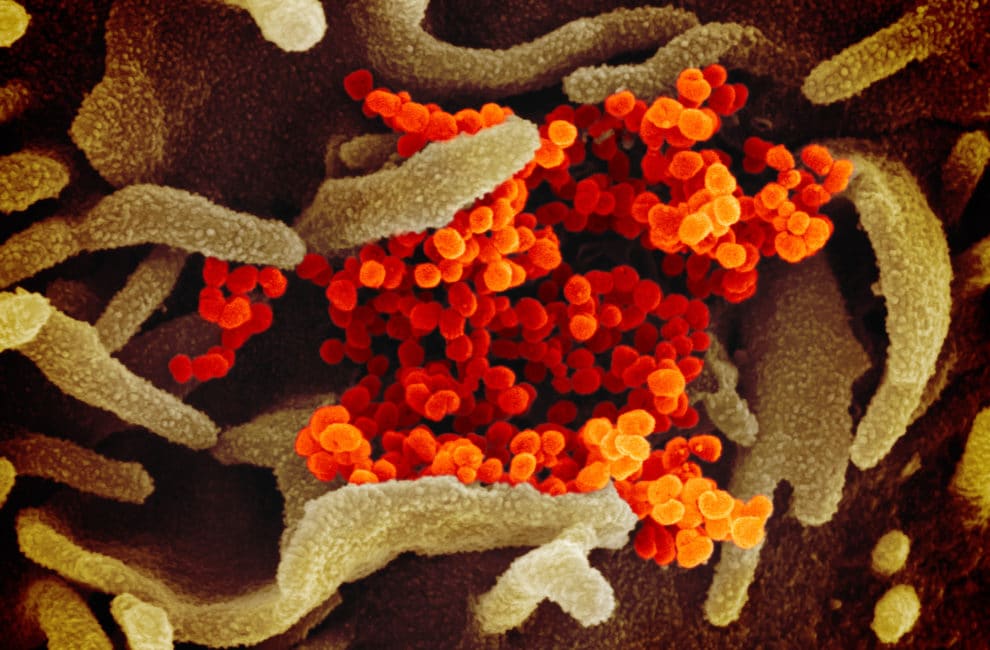

This scanning electron microscope image shows the virus that causes COVID-19 isolated from a patient in the U.S., emerging from the surface of cells (green) cultured in the lab. Photo by NIAID-RML

We’re all in this together, right?

Not according to a new neighborhood-level dataset produced by the Polis Center at IUPUI—not on equal socioeconomic footing, at least.

The Polis Center data juxtaposes information from the U.S. Census Bureau and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s 500 Cities Project.

The coronavirus will disproportionately wreak havoc on the city’s neighborhoods that already fare the worst on all kinds of metrics, ranging from lack of health insurance to the highest concentration of pre-existing conditions.

The findings estimate the location of high-risk populations within the city. And, mirroring national data, the coronavirus is likely to have a disproportionate effect on communities of color, revealing a city deeply divided by class and race.

“The Polis Center’s data shows that many of the same areas of the city facing challenges with crime, food insecurity and lack of food access, and high rates of chronic health issues are correspondingly facing a higher risk of COVID-19 impact,” says Taylor Schaffer, Mayor Joe Hogsett’s deputy chief of staff.

The Polis findings:

- “Neighborhoods just outside of downtown Indianapolis have the highest estimated risk when it comes to factors that are related to income.”

- “The neighborhood just north of 30th Street and east of Fall Creek (tract 3508.00) has one of the highest socioeconomic risk index scores. In this neighborhood, an estimated one-fifth of the population lacks health insurance, one-sixth of adults have asthma, one-third smoke, and a quarter have diabetes.”

- “The area near New York Street and Sherman Drive also rates as very high risk on this index due to a high concentration of people who lack health insurance, have asthma, and smoke.”

- “The Martindale-Brightwood and Meadows neighborhoods (northeast of downtown) have high estimated rates of heart disease and some pockets of older populations. The Far Eastside and the far southside (near U.S. 31 and County Line Road) also have high risk populations according to the age-related risk factors.”

Asked whether the city is prepared to respond, Schaffer pointed to Hogsett’s Office of Public Health and Safety. Hogsett created the office in 2016 to address the kind of systemic public health challenges highlighted in the COVID-19.

The office exists to improve residents’ immediate needs, whether that’s helping them find food banks or hot meal sites through Facebook Messenger, or protecting them against shady landlords; and future needs, such as connecting them to jobs that pay at least $18 an hour.

“OPHS is rigorously focused on developing policies to address violence reduction, food access, and food insecurity,” Schaffer said. “The current COVID-19 pandemic has only highlighted the urgency of the need for OPHS’s work in these areas—particularly the need to focus on communities most impacted by these underlying issues.”