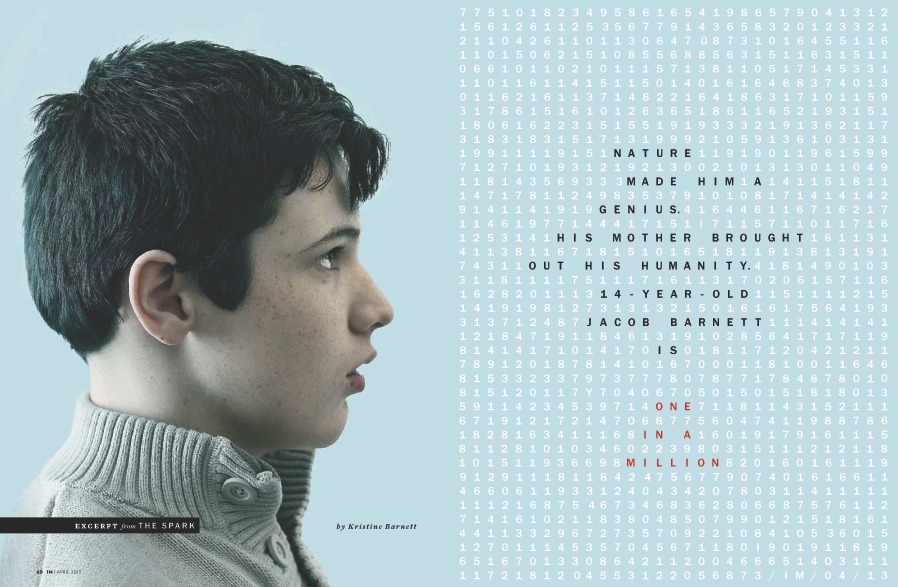

Boy Genius

For a kid with autism, Jacob Barnett did a lot of communicating over the last two years. The 14-year-old Hamilton County boy (IQ 170) became history’s youngest published astrophysics researcher, spoke at a TEDx conference in New York, and appeared on 60 Minutes and on Time magazine’s website. All of this from a child who, a few years ago, was expected to have trouble ever tying his own shoes.

A lot of the credit goes to his mother, Kristine Barnett, who discovered a novel way to bring him out of his shell. This month, Random House will release The Spark, her memoir about raising Jacob. And while the boy’s story is extraordinary, Kristine feels it holds important lessons for all parents. “It’s really not just a story about a child genius,” she says. “What I learned in helping Jacob applies to all children. He faced a lot of problems early in life, and our tendency is to spend all our time trying to fix those. So it was very controversial for me to spend so much time working with him on the things he was passionate about—the puzzles he could solve so quickly, the piano-playing. Those had always been in the background of the things he couldn’t do.”

Jacob ultimately thrived and now tutors and does physics research at IUPUI, allowing Kristine to run a daycare. But in the following excerpt from The Spark, that happy ending was by no means a foregone conclusion. If the heartwrenching scenes remind you of something from a movie, you might be on to something—Warner Bros. has optioned the book for a film. That can only help the international book tour that’s about to whisk the family away to Europe, where Jacob is looking forward to visiting the Large Hadron Collider outside of Geneva. By July, however, his mom hopes the publicity will be behind them.

“My goal for the summer is just to give him a few weeks off,” she says. “The last time he had that was when he came up with the alternative theory to the Big Bang. So who knows what he’ll create?” —Daniel S. Comiskey

[EXCERPT: THE SPARK]

November 2001

JAKE, AGE THREE

“Mrs. Barnett, I’d like to talk to you about the alphabet cards you’ve been sending to school with Jacob.”

Jake and I were sitting with his special ed teacher in our living room during her monthly, state-mandated visit to our home. He loved those brightly colored flash cards more than anything in the world, as attached to them as other children were to love-worn teddy bears or threadbare security blankets. The cards were sold at the front of the SuperTarget where I did my shopping. Other children snuck boxes of cereal or candy bars into their mothers’ shopping carts, while the only items that ever mysteriously appeared in mine were yet more packs of Jake’s favorite alphabet cards.

“Oh, I don’t send the cards; Jake grabs them on his way out the door. I have to pry them out of his hands to get his shirt on. He even takes them to bed with him!”

Jake’s teacher shifted uncomfortably on the couch. “I wonder if you might need to adjust your expectations for Jacob, Mrs. Barnett. Ours is a life skills program. We’re focusing on things like helping him learn to get dressed by himself someday.” Her voice was gentle, but she was determined to be clear.

“Oh, of course, I know that. We’re working on those skills at home, too. But he just loves his cards . . .”

“I’m sorry, Mrs. Barnett. What I’m saying is that we don’t think you’re going to need to worry about the alphabet with Jacob.”

Finally—finally—I understood what my son’s teacher had been trying to tell me. She wanted to protect me, to make sure I was clear on the objectives of a life skills program. She wasn’t saying that alphabet flash cards were premature. She was saying we wouldn’t ever have to worry about the alphabet with Jake, because they didn’t think he’d ever read.

It was a devastating moment, in a year that had been full of them. Jake had recently been diagnosed with autism, and I had finally come to understand that all bets were off as to when (or whether) Jake would reach any of the normal childhood developmental milestones.

Ironically, I wasn’t hopeful that Jake would ever read, but neither was I prepared to let anyone set a ceiling for what we could expect from him, especially one so low. That morning, it felt as if Jake’s teacher had slammed a door on his future.

For a parent, it’s terrifying to fly against the advice of the professionals, but I knew in my heart that if Jake stayed in special ed, he would slip away. So I decided to trust my instincts and embrace hope instead of abandoning it. I wouldn’t spend any time or energy fighting to convince the teachers and therapists at his school to change their expectations or their methods. I didn’t want to struggle against the system or impose what I felt was right for Jake on others. Rather than hiring lawyers and experts and advocates to get Jake the services he needed, I would invest directly in Jake and do whatever I felt was necessary to help him reach his full potential—whatever that might be.

That misunderstanding was a clarifying moment for me. My husband, Michael, and I were sending Jake to school to learn. But his teachers—the people responsible for his education—were telling me they didn’t think he could be taught. As gentle as Jake’s teacher had been with me, the underlying message was clear. She had given up on my son.

Later that day, while I was taking a chicken out of the Crock-Pot for dinner, I tried to talk it through with Michael. “He’s not going to read? Ever? Why not at least try? This is a kid who’s already totally obsessed with the alphabet without any encouragement at all. Why hold him back from what he’s naturally doing?”

Michael was slightly exasperated with me. “Kris! These people have a lot more experience and training than we do. We have to let the experts be the experts.”

“What if carrying around alphabet cards everywhere he goes is Jake’s way of saying he wants to read? Maybe it’s not, but what if it is? Do we want him with people who won’t even try to teach him simply because it’s not part of the life skills program? Why would they say no to somebody who wants to learn?”

I realized that all of my questions—indeed, all of the niggling doubts I’d been unable to squelch in the months since Jake had started preschool and even before that—could be boiled down to one big, basic issue: Why is it all about what these kids can’t do? Why isn’t anyone looking more closely at what they can do?

The next day, I did not put Jake on the little yellow school bus. Instead, he stayed home with me.

I set up new routines for Jake. But instead of constantly pushing him in a direction he didn’t want to go, drilling him over and over to get his lowest skills up, I let him spend lots of time every day on activities he liked.

For instance, Jake had moved from simple wooden puzzles to complicated jigsaws, blowing through thousand-piece puzzles in an afternoon. (One Saturday afternoon, when we were trying to complete the last, frustrating part of a house project, Michael dumped all the pieces from five or six of those puzzles into the gigantic bowl I use for popcorn on our family movie nights. “That should keep him busy,” he said. It did—but not for long.)

He also loved the Chinese puzzles called tangrams—seven flat, oddly shaped pieces that you put together to form recognizable figures. I found it incredibly difficult to arrange these irregular shapes so that they resembled an animal or a house, and I always had to shuffle them around, trying many different options before landing on the right arrangement. Jake, however, seemed to have no trouble flipping and rotating the shapes in his mind. Then he’d lay the pieces out easily, as if that was the only way they went. Soon we began combining sets, making large-scale patterns that were much more beautiful and complex than anything the instruction cards suggested.

I spent as much time doing puzzles and tangrams with him as I’d once spent on therapy, and slowly I began to see a change in him. He was more relaxed, more engaged. Over the next month or so, he regained some of the ground I felt he’d lost while he was in school. In particular, Jake’s language began to come back. It wasn’t conversation—I couldn’t ask him a question and get a response, for instance—but he was talking.

Most of the time, he recited strings of numbers. Numbers had always been comforting to Jake. He would carry an old grocery receipt around for a week, smoothing the list of numbers under his fingers. Once the floodgates were open, Jake was actually quite chatty. We couldn’t pass a numerical street sign or an address that he didn’t read out loud. Running errands with me in the car, he’d call out a constant stream of numbers from the backseat.

This was how we figured out that Jake already knew how to add. At some point, I realized that some of the numbers he was saying were telephone numbers that he was reading off the sides of the commercial trucks and vans that we passed on the road. But there was always an extra, larger number at the end of the series—and I practically drove off the road the day I figured out the final number was the sum of the ten digits in the phone number added together.

Driving back from a doctor’s appointment, I caught fragments of what Jake was saying to himself in the backseat. This time, it wasn’t only numbers but the license plates of the cars we were passing. Then it was the names of the businesses: “Marsh!” “Marriott!” “Ritter’s!” At age three, just a few months after his teacher had told us we wouldn’t ever have to worry about the alphabet with him, Jake could read. I really didn’t know how he had learned or when it had happened—maybe it had been that Cat in the Hat CD-ROM after all. All I knew was that I had never gone through any of the typical pre-reading steps with him that I’d taken with so many other children in the daycare I ran, teaching them the alphabet and all the different ways letters can sound. I had never so much as sounded out a single word with Jake. And yet now that he was talking a little more, we were learning that I wouldn’t have to.

Going to the grocery store with Jake during that period took forever. Before I could put an item in the cart, I had to tell Jake how much it cost so that he could say the number back to me. This drove me crazy. One day about six months after we’d pulled him out of special ed, I was swiping my credit card at the checkout counter, and Jake started yelling, “One-twenty-seven! One-twenty-seven!” I couldn’t get him out of the store fast enough, but when I did and had the presence of mind to check the receipt, I saw that he must have been totaling up the prices as I was putting the items in the cart. The checkout person had accidentally rung up a bunch of bananas costing $1.27 twice. After that day, he always gave me the running total as we joined the checkout line.

The “math people” in our lives found Jake fascinating. One day I was having a cup of coffee with my aunt, a high school geometry teacher, while Jake sat at our feet, playing with a cereal box and a bunch of Styrofoam balls I’d gotten from a craft store so that the daycare kids could make snowmen. He was putting the balls into the box, taking them out, and then doing it again, and it sounded as if he was counting. My aunt wondered aloud what he was doing.

Jake didn’t look up. “Nineteen spheres make a parallelepiped,” he said.

I had no idea what a parallelepiped was; it sounded like a made-up word to me. In fact, it’s a three-dimensional figure made up of six parallelograms. Jake had learned the word from a visual dictionary we had in the house. And yes, you can make one out of a cereal box. My aunt was shocked, less by the fancy word than by the sophisticated mathematical concept behind it.

“That’s an equation, Kristine,” she said. “He’s telling us that it takes nineteen of those balls to fill a cereal box.” I still didn’t understand the importance of what he was doing until she explained to me that an equation was a concept that she saw kids in her tenth-grade class struggling with every day.

Michael and I marveled at the evidence of his precocity, but in truth, the new normal was still hard. In particular, we weren’t making much progress on real conversation. He was talking again, and for that we were grateful. But reeling off numbers and store names and answering questions are different from engaging in conversation. Jake still didn’t understand language as a way to make a connection with other people. He could tell me how many dark blue cars we’d seen on the trip to Starbucks, but he couldn’t say how his day had been, and I was always searching for common ground.

Also, Jake’s extraordinary academic abilities wouldn’t really help us to mainstream him into public school. Simply put, social skills are far more important than academics in kindergarten. Kids in kindergarten have a lot of playtime. They have to interact with their classmates, they have to follow simple directions and share. If Jake spent the whole day in the corner, even if he was teaching himself the periodic table, they’d send him right back to special ed.

It was imperative that Jake learn to function well in a group. Of course, he was around the kids in daycare every day, but his therapist Melanie Laws thought it might be easier for him if there were other autistic kids in the group as well. With her help, I sent an email out to the parents in our community, hoping some of them might want to join.

My call for participation was the first real clue that there was an autism epidemic. I was hoping for five or six responses. Instead, I got hundreds, from parents of children of all ages. I was stunned by the level of desperation in the emails. These were people, just like me, who could see that what they were doing wasn’t helping their children. Many of them had run out of options within the system. There wasn’t any place left that would work with them or their kids. In most cases, I was the port of last resort. “Please help us,” one mother wrote. “You’re our last hope.”

That was a huge turning point for me. I looked at my flooded inbox and thought, I’m not going to turn any of you away. You can all come. Jake was going to learn what he’d need to get into kindergarten, and we were going to take as many kids with us as we possibly could. Nor would we leave the older or lower-functioning kids behind. We are going to build a community, I thought. We are going to believe in our kids, and in each other’s kids, and we are going to do this together.

Not long after we pulled him out of special ed, it became clear that Jake’s particular passion had to do with astronomy and the stars. By age three, he could name every constellation and asterism in the sky. I believe Jake’s interest in the planets had its roots in his obsession with light and shadows, which we’d noticed even when he was a tiny baby.

Right after we started Little Light, a preschool for autistic children, Jake became preoccupied with a college-level astronomy textbook someone had left unshelved on the floor at the Barnes & Noble near our house. The book was huge for such a little boy, but he dragged the cover open and then sat absorbed in it for more than an hour.

It was certainly not a book for a three-year-old. Taking a peek over his shoulder, I was put off by the minuscule text and arcane content. Most of the pages were taken up by maps of different parts of the solar system. There was no narrative at all—no retelling of the Greek myths that gave the constellations their names, not even any scientific explanations—just maps. My eyes glazed over as I flipped through it. What did Jake want with this book?

To my complete surprise, that cumbersome book became Jake’s constant companion. Its heft meant that his only way of transporting it around the house was to open the cover and drag it with both hands. After a while, it got so beat-up that Michael had to reinforce the spine with duct tape. Every time I looked through it, I couldn’t believe that this highly technical manual, clearly intended for advanced astronomy students, could possibly be of interest to my little boy.

But it was, and it turned out to be an in. I always felt a little bit like a detective at Little Light. Whatever the children loved would set us to following the bread crumb trail, finding out bit by bit who they really were. I knew Jake’s fascination with this book, as impenetrable as it might have been, was an important clue. So when I saw in the paper that the Holcomb Observatory, a planetarium near our house on the campus of Butler University, would be doing a special program on Mars, I asked Jake if he’d like to go see Mars through a telescope. You would have thought I’d asked him if he wanted ice cream for breakfast, lunch, and dinner. He pestered me so mercilessly about it that I thought the day would never come.

In our excitement, we arrived a little too early. The grounds were beautifully maintained, and we found an enormous grassy hill to roll down right by the planetarium’s parking lot. At the bottom, by a little pond, we found hundreds of horse chestnuts lying in the grass under the trees. While the sun set, we walked slowly around the pond, and Jake picked up as many of those chestnuts as he could carry, packing them into his pockets and filling the fuzzy dog-shaped backpack he took everywhere. The chestnuts were pleasantly round and smooth, and I could see that Jake liked the way they felt in his hands. By the time the doors to the planetarium opened, his pants pockets were as stuffed as a squirrel’s cheeks.

The lobby was spectacular, but almost instantly I wished we were back outside. I’d thought we’d be able to zip in to get a quick look through the telescope without disturbing anyone, but I discovered that to look through the telescope, we’d have to take a tour of the planetarium. Worse still, as I learned after we’d already waited in line and bought tickets, the tour included an hour-long, college-level seminar given by a professor at Butler. As the lobby began to fill up with people, the knot in my stomach intensified. A college-level presentation in a silent, crowded auditorium was not at all what I’d had in mind, and it was the last place on earth anyone in her right mind would voluntarily take an autistic three-year-old.

Eventually, the doors to the lecture hall opened, and the crowd filed in. As soon as we got inside, I thought, Oh, boy, this whole thing is about to go bad. The room was small and hushed; a PowerPoint presentation was ready to go. The first slide had to do with nineteenth-century telescope resolution. The only seats left were right up front.

I started digging through my bag, desperate to find something—animal crackers? a crayon? some gum?—that might stave off a complete meltdown. By the time the lecturer stepped up to the podium, I was in a near panic, and it only got worse. As the slides started clicking by, Jake began reading, quite loudly, some of the words popping up on the screen: “Light year!” “Diurnal!” “Mariner!”

I shushed him, sure the people around us were going to give me the stink eye, hissing at me to get my kid out of this place we clearly had no business inhabiting. Sure enough, the people around us were starting to notice, and to whisper, but it soon became clear that they weren’t so much annoyed as they were amused and a bit incredulous.

“Is that little kid reading?” I heard someone say. “Did he just say ‘perihelial’?”

Then the lecturer introduced a history of scientific observations about the possibility of water on Mars, starting with the nineteenth-century Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli, who believed he saw canals on the planet’s surface. Hearing this, Jake started to laugh. In my anxiety, I thought he was going to lose it, but when I looked at him, I could see he was genuinely cracking up, like the idea of canals on Mars was the greatest knee-slapper he’d ever heard. Again, I quieted him down. But I could see the ripple spread through the crowd as people started craning their necks to see what was going on.

Then the lecturer asked a question of the audience: “Our moon is round. Why do you think the moons around Mars are elliptical, shaped like potatoes?”

Nobody in the crowd answered, probably because no one had the slightest idea. I certainly didn’t. Then Jake’s hand shot up. “Excuse me, but could you please tell me the size of these moons?” This was more conversation than I’d seen from Jake in his entire life, but then again, I’d never tried to talk to him about Mars’s moons. The lecturer, visibly surprised, answered him. To the astonishment of everyone, including me, Jake responded, “Then the moons around Mars are small, so they have a small mass. The gravitational effects of the moons are not large enough to pull them into complete spheres.”

The room went silent, all eyes on my son. Then everyone went nuts, and for a few minutes the lecture came to a halt.

The professor eventually regained control of the room, but my mind was somewhere else. I was completely freaked out. My three-year-old had answered a question that had been too difficult for anyone else in the room, including the Butler students and all of the adults present. I felt too dizzy to move.

At the end of the lecture, people crowded around us. “Get his autograph. You’ll want that someday!” someone said. Another person actually pushed forward a piece of paper for Jake to sign, which I pushed right back. Usually overwhelmed by crowds, Jake took everything happening around him in stride, staring contentedly at the last PowerPoint slide, a close-up satellite shot of an enormous mountain on the surface of Mars.

I wanted nothing more than to get out of there. But when it came time for everyone to make their way upstairs to look through the telescope, an astonishing thing happened. The crowd fell back to let Jake go first. The entire auditorium had wordlessly united behind the same goal: Let’s get this kid upstairs to see Mars! I know it sounds crazy, but there was a reverence in the air. Jake and I went up the stairs, buoyed by the energy and hopefulness and goodwill of the group. I felt almost as if they were carrying us.

As we drove home that night, Jake couldn’t stop chattering about space. I could finally understand what he was saying, but all it did was freak me out even more. How did this child know the comparative densities and relative speeds of the planets?

After I tucked Jake in, I called my friend Alison. Alison’s son Jack was also autistic and the same age as Jake, and we had become dear friends. I told her everything that had happened during our evening at the planetarium. Reliving it raised goose bumps on my arms.

“What am I supposed to do with this child?” I asked her. “Should I be doing something more, something different? Seriously, should I take him to NASA or something?”

I have thought about that moment again and again in the years since. Like the decision to pull him out of preschool, it was a turning point. We could have gone down a very different road, one I clearly see now would have been wrong for us. I am so grateful to Alison for her good sense. “You do exactly what you’re doing right now,” she told me. “You play with him, and you let him be a little boy.”

As I fell asleep, I knew that Alison was right. The things that made Jake special weren’t going anywhere. He would make his mark eventually—that much was becoming clear—but right now he needed to be comfortable and happy at home with us. He needed to go to school, to have friends, and to share in family rituals such as going out for pancakes and making s’mores in the backyard. We were going to eat gummy bears and watch VeggieTales. For now, Jake would be a regular kid.

After so much agonizing time searching for him, I could finally catch my breath. I’d found my son.

Even so, that evening at the planetarium, something shifted for me. Michael and I understood that Jake was more than just a smart kid, but he had stunned me, the lecturer, and everyone else in the auditorium with a level of knowledge about the solar system that was frankly bizarre. Suddenly, I was able to see all the cute and remarkable and sometimes odd things Jake could do for what they were: extraordinary.

I had never experienced anything like the awe and veneration I felt from the crowd in that lecture hall. In some ways, that shocked me more than Jake’s answer, or anything he told me about the radius of Betelgeuse on the way home. Those people in the planetarium had been inspired, transported to a better place, and they had been delivered there by Jake. That night, I had the distinct feeling—which has never been very far away since—that Jake was going to use his amazing brain to make a significant contribution to the world.

In the meantime, though, I had to get him into kindergarten.

THE SPARK: A Mother’s Story of Nurturing Genius, by Kristine Barnett. Copyright 2013. Published by Random House and available now.

Photos by Tony Valainis

This article appeared in the April 2013 issue.