Party of Five: The Gaither Quintuplets Turn 30

Thirty years ago this month, more than 50 IU Hospital doctors and nurses escorted Suzanne Gaither into the operating room to give birth. The 21-year-old student-loan analyst and her husband, Sidney, a 32-year-old service manager for an elevator company, were about to become the parents of America’s first African-American quintuplets—and the first set in 20 years that wasn’t the result of fertility drugs.

For two months, Suzanne had been on bed rest to prevent early labor. Now it was time. On August 3, in a span of 30 minutes—the period it usually took to perform one Caesarean section—two boys and three girls “popped out from the pressure,” Dr. Frank Johnson said after the delivery. Ashlee, Joshua, Renee, Rhealyn, Brandon.

Multiple births have long fascinated the public, perhaps most strongly since 1934, when the Dionne quintuplets, the first set to live past infancy, became something of a tourist attraction in their native Canada. The Gaithers were no different, enthralling not only Indianapolis—whose citizens showered the northwestside family with attention, a mayoral proclamation, and fund-raisers—but the nation. At the time, only about one in 40 million women gave birth to quints without fertility treatment.

Journalists from major media outlets rushed to Indy to report the historic news—including me. As a new editor at Jet magazine in Chicago, I was the first reporter to interview Suzanne Gaither in her hospital room. Two days after the quints’ arrival, Suzanne cradled four of the babies in her arms as she rested in bed. One quint was missing. Ashlee, the firstborn, was in critical condition with an enlarged heart and had to remain on a respirator. She was not expected to survive.

Today, Ashlee starts to cry when she thinks about turning 30. “I always get emotional at every birthday,” she says, sitting at a dining-room table at her sister Rhealyn’s northwestside home. Ashlee is now healthy, though she often uses a wheelchair for ease. Her voice shakes and drops down to a whisper: “I wasn’t supposed to be here.”

Her siblings move to comfort her. Joshua jumps up to find a tissue. Renee reaches over and touches her on the shoulder and says, “Oh, Ashlee, it’s okay. It’s okay.” Joshua gently wipes away his sister’s tears. Brother Brandon speaks from across the table. “Those doctors gave you that 50-50 chance of survival. But the ultimate person who determines that is God. Ashlee, you proved the doctors wrong.” Rhealyn chimes in. “People might look at Ashlee because she walks a little different or uses a wheelchair, but Ashlee will look at them and laugh,” she says. “Our parents told Ashlee to laugh at people when they stare [and are] being judgmental and silly.”

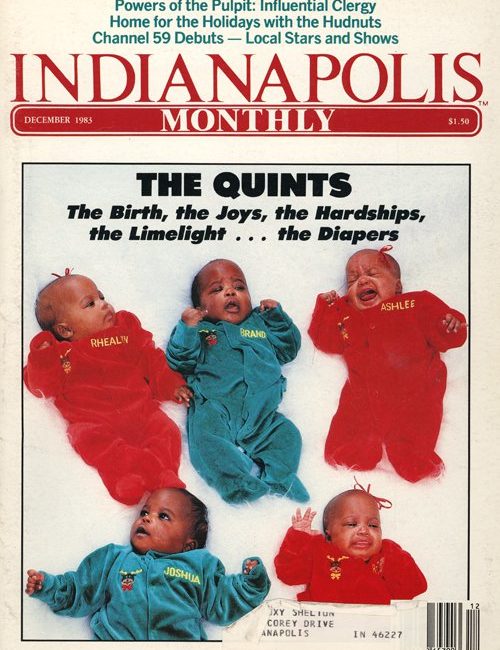

Indeed, the five learned to adjust to all manner of attention. Media favorites especially in the first few years of their lives, the quints were featured on the Today show, Donahue, and The Maury Povich Show. Ebony magazine put them on its cover—as did Indianapolis Monthly the December after they were born, five tiny babies in red and green. They even starred in a McDonald’s commercial.

Their parents, though, were determined to “protect them and raise them in an atmosphere that was as normal as possible,” Suzanne says. She and Sidney did not hire a publicist and were skeptical about people who wanted to represent their children. One high-profile promoter tried to convince them to hand over almost total power of the quints. “This contract would have determined the children’s schedule, their every move,” recalls Suzanne. “If the promoter wanted them in New York on Monday and today is Friday, we would have to make it happen. We would not have had any rights, any say-so in our children’s lives, no control over anything. We were not going to do that. We promised ourselves that we would not allow our children to be exploited.”

With each media-related decision, Suzanne and Sidney questioned whether the quints would be pleased with the exposure down the road. “Before we said yes to the McDonald’s commercial, we asked ourselves, ‘Will they be happy they did this when they look back? Will they be proud to show their own children?’” says Suzanne.

The quints appreciate the way their parents protected them from too much fame. “Even as kids, we could say yes or no [to any opportunities], and all five of us had to agree,” Ashlee says. “Otherwise, we would not do it.”

Outside the spotlight, the day-to-day business of raising the quints and their older brother, Ryan, involved a lot of help, both physically and financially. Two kind-hearted women in the community volunteered to help out with the babies—who usually went through 50 bottles and 50 diapers a day, and 100 jars of baby food a week—while Suzanne and Sidney went back to work. “I was there when they took their first step and cut their first tooth,” recalls caregiver Connie Moore, now 79, on her way to Rhealyn’s son’s preschool graduation one recent Saturday. “And I remember they were easy to potty train. They put pressure on themselves, ‘Oh my brother can do it, now I can do it, too,’” she says with a laugh.

“It seems like just yesterday they were crowded in my office—all five of them, three caregivers, and their mother. We had to block out the entire morning, about four hours, to make sure I could treat each of them.” —Dr. John T. Young, 86, pediatrician

Volunteer Hazel Cork, 81, was also there “from the day they came home from the hospital until the day they started preschool,” Cork says. “Aunt Hazel”—as the quints call her—and Moore had their hands full “keeping the kids in one room when they loved to crawl all around the house.”

And that family of eight required a bit more square footage than the three-bedroom ranch that Suzanne and Sidney lived in when the quints arrived. By the time the children turned 2, the family had moved to a five-bedroom home on the northeast side, thanks to corporate sponsorships and contributions from the likes of Gerber as well as a local radiothon that raised $50,000.

Even a simple trip to the doctor, though, could be an ordeal. “It seems like just yesterday they were crowded in my office—all five of them, three caregivers, and their mother,” says Dr. John T. Young, 86, their pediatrician. “That’s nine people for one visit. I can handle one or two babies, but five was a bit of a challenge.” He laughs. “We had to block out the entire morning, about four hours, to make sure I could treat each of them.”

Otherwise, the quints enjoyed a relatively ordinary childhood. They attended Auntie Mame’s daycare, John Strange Elementary, Eastwood Middle, and North Central High. But “they were not always lumped together as a group,” says Suzanne. “For the most part, the quints did not take classes together.” She and Sidney made sure the five developed as individuals “who just happened to share the same birthday,” says Suzanne, not as an indistinguishable unit.

As such, each developed a distinct personality. Brandon is “Daddy Jr.,” the serious one with a strong spiritual side, like Sidney. “Most of the CDs in my car are gospel,” he says. Joshua is the outgoing “life of the party,” and Rhealyn, the self-described “mother hen” and “commander-in-chief,” is the most like their mother. “At age 2, Rhealyn was the leader,” says Suzanne. “During treat time, each of them would come to me to get cookies. Rhealyn would take the bag and pass out the cookies so that everyone was happy.” And while the boys shot baskets outside and the other two girls played Nintendo, Rhealyn watched her mother prepare meals in the kitchen. By 11, she could cook meatloaf and macaroni and cheese for dinner. Renee, on the other hand, is soft-spoken and somewhat shy, a gifted athlete with a keen sense of humor. Ashlee is the practical, “go-to” sibling—the one they all come to for advice.

“Why go on national TV and tell everything? You have to sell your soul. I’m glad we didn’t do that. I don’t know how much of a real childhood we would have had coming up today as quintuplets.” —Rhealyn, on reality-TV opportunities

Brandon and Joshua, though, are the closest, and claim they can feel when something is amiss with each other. “I used to get nosebleeds when there was something wrong with him,” says Joshua. Brandon agrees: “If there is something wrong with Josh, I can tell and will call him or text and ask if he is okay. It is weird.” Brandon remembers one time when Joshua hurt his foot at work. “I got a sharp pain going down my knee, and I called him and said, ‘Are you okay?’ He said, ‘My foot is hurting really bad.’ I told him, ‘I am feeling your pain.’”

The rest of the quints may not have that sort of physical connection, but they can still tell by each other’s voices when something is awry. “That comes from us spending a lot of time together,” admits Rhealyn. They each live about a 15-minute drive from one another in Indy and get together once a week for dinner, usually at Rhealyn’s house, even as their lives shift and evolve. Brandon, an international shipper for a merchandising company, and Joshua, who works for an airline, are both divorced, and each has two children. Rhealyn—the assistant to the president at Mid-America Elevator Company, where Sidney works—and Renee, a specialist at Methodist Hospital, are married, the former with two children and a stepdaughter. Ashlee, who has an associate’s degree in liberal arts from Ivy Tech, is single and plans to earn a bachelor’s in political science.

Sidney is now assistant vice president of sales at Mid-America Elevator Company and a church trustee and lay minister at Zion Tabernacle Apostolic Faith Church. The quints grew up in the congregation, with senior pastor Thomas E. Griffith as a mentor. “There was a lot of stress having a family grow that large that quick,” Sidney says. “I thought to myself, ‘How will I provide for them?’ But we made it through by the grace of God. We’ve been blessed.”

Suzanne retired from her job as a loan analyst in 2004. “Sidney stood up and took care of his family. He always worked hard, up at sunrise, home at sunset. Back then he was on call 24 hours a day at the elevator company,” she says. “If the elevators were down, he would have to rush out to repair them. He would go without hesitation.”

In addition to years of hard work, other community and corporate contributors supplemented the Gaithers’ salaries at times, and the media returned to revisit the Gaithers as well. The Associated Press covered them getting ready for the junior prom in 2001, and Today captured their high-school graduation a year later. While the quints toyed with the idea of being on a reality show when they turned 25, they never sought widespread exposure like, say, the parents of the Gosselin sextuplets, whose every move was the subject of TLC’s Jon & Kate Plus 8 and Kate Plus 8.

“Why go on national TV and tell everything?” says Rhealyn. “You have to sell your soul. I’m glad we didn’t do that. I don’t know how much of a real childhood we would have had coming up today as quintuplets. I don’t know if we would be as close, tight-knit, and grounded as we are.”

“I can’t wait to see us at 50,” says Joshua. “One thing I know for sure—we will still be close.” That includes big brother Ryan, who will meet them at Disney World this month. There, they will celebrate their 30th birthdays just as they marked their 10th. “I’m just glad everyone is healthy, grown up, mature, and doing good,” Ryan says from his home in New York. “It really means the world to me that we are just as close now as when we were kids.”

As for their place in history as the nation’s first surviving African-American quintuplets, “Our legacy will live on with the voices and footsteps you hear running upstairs, right now—our children,” says Brandon. “Family is everything.” Suzanne and Sidney agree; the couple has nine grandchildren, and when the little ones visit, it almost feels like the old days, when the quints and Ryan were growing up. But there is one big difference, says Suzanne: “Now we love them, spoil them—and send them back home.”

Gaithers 2013 photo by Dale Bernstein; IM photos by Tony Valainis

This article appeared in the August 2013 issue.