Phil Gulley: Strong Foundation

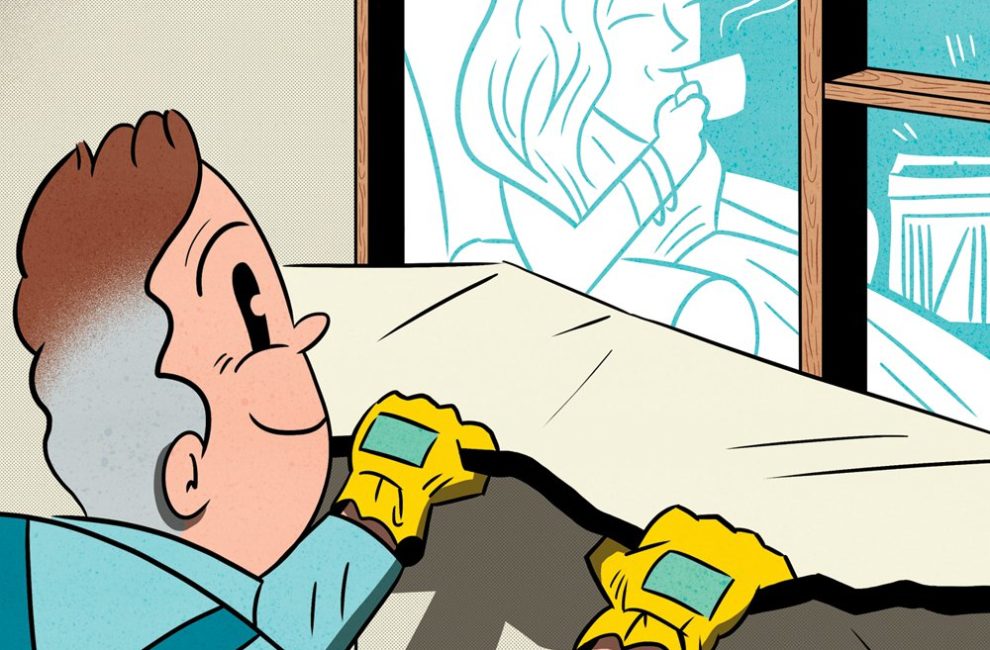

Last summer, Mrs. Chandler’s house and eight acres next to my son’s place went on the market. My son wanted the land, and I had my eye on the small house sitting on it, so we pooled our money and bought the property. The surrounding countryside is being carved up into five-acre tracts, so it was predicted that whoever bought the property would knock down the existing building and put up some God-awful monstrosity. But there is something in me that cannot abide tearing down a perfectly good house, so my son and his helper began renovating it.

The word “renovate” hails from the Latin renovare, which means “to make new again” and sums up our efforts. We’ve stripped the house down to its skeleton, inside and out, and are starting over with new siding, insulation, drywall, doors, windows, flooring, wiring, paint, and a roof. The house has been full of surprises, the most curious so far being a cellar we were assured didn’t exist. But when we pulled up the carpet in a bedroom closet, we found a trapdoor opening to it. The subterranean space was full of empty canning jars from when Mrs. Chandler had a garden and put up food. The faint outline of gardens past is still visible in the backyard.

We’ll move into our “new” home when we no longer want to wander aimlessly in a two-story house—a place that made sense when our sons were here but now feels like an empty husk, with rooms we don’t enter for weeks at a time. That won’t be the case with the new house, which is half the size of our present one and has only five rooms, each of them simple and pleasant.

When it comes to housing, many people favor quantity over quality, opting for space over beauty. But I’ve been fond of small spaces since I was a kid and made blanket forts under the kitchen table. I don’t like two-story entrances or master suites. I do like woodstoves and have been trying to figure out where to wedge one in, without much luck. My son is building a barn in the back field. I might put a woodstove in it and go sit with the cows to read my newspaper.

One evening, I was alone in the house pulling off drywall in the living room and thought of Mrs. Chandler. When I got home, I went online and read her obituary. It mentioned she had twin daughters, both of whom died in infancy. I wondered if she and her husband were living in that house when their daughters died, and what the walls would tell of that awful day. A house gives off vibes, and no matter how bad that tragedy might have been, I sense the majority of their time there was good. The place has a pleasant feel, a soft warmth.

Sometimes you have to live in a house for a while before she trusts you enough to reveal her secrets.

There are hints that suggest this is the second house on the property, that this one was built over the cellar of the first. Between the house and the back field are several foundations from old outbuildings. I was poking around in a thicket of trees and found an old grinding stone. If I were clever, I’d make something from it for the house, but I’ll probably just store it in the barn and leave it for my grandchildren to play with.

There are a few things about the house that give me pause. Neither I nor the county health department has any idea where the septic system is. The water disappears when we flush the toilet, which is a good sign, so I’m inclined to leave things as they are. One can pry too much, ask too many questions of a house, and receive answers he might not like. My other concern is the lack of a suitable front porch. I have not yet figured out how to add one without it looking like an afterthought. Sometimes you have to live in a house for a while before she trusts you enough to reveal her secrets.

Four apple trees grace the property, strung in a line by the road, and two persimmon trees, one of each gender in order to produce fruit. If a farmer took the trouble to plant a tree, it had to pay its way with shade, windbreak, or food. The ornamental trees planted these days would have been cut down as weeds by past generations. I like trees to tower over a house, even if every now and then one falls and punches a hole in the roof. Like the half-buried grinding stone, some of the trees predate the house, another indication the land enjoyed a previous life. I suspect someone has lived on this parcel of ground since around the Civil War.

One of the outbuildings, now gone, was made of bricks fired in Brazil, Indiana, in the late 1800s. I’ve been digging them up ever since we bought the place. Mrs. Chandler used some of the bricks to line her flower beds. I might make a brick sidewalk if I have enough. There’s no sidewalk from the driveway to the front door, a curious omission. It tells me the Chandlers were informal people whose friends entered by the back door into the kitchen. I’m informal too, but I still like a front sidewalk, so the Jehovah’s Witnesses can’t sneak up behind me.

Our neighbor to the north was Mrs. Marian Worrell. I say “was” because she died last summer at the age of 104. She taught school in our town for 29 years, and one of those years I learned under her kindly lash. She attributed her long life to her genes, but I hope it was her drinking water, since our wells tap the same aquifer. After we move in, maybe I’ll experience a surge of vitality and live another 50 years.

Four fieldstone pillars flank the driveway, marking the property boundaries. They’re in bad shape, tilted and shedding stones, so I’m on the lookout for a good stone man. For that matter, I’d take a good stone woman, a good stone anyone being hard to find these days. The stones came from the field, heaved up by the plow and cold, and stacked in piles at the field’s edge. Not enough to make a stone wall, but enough to make four once-handsome pillars marking the beginning of one man’s kingdom and the end of another’s.

When I was a kid, I rode my bicycle past this house hundreds of times. Had I known I would one day own it, I would have stopped to ask Mrs. Chandler where the septic system was. This has been a sad and constant theme in my life, that by the time I get around to asking a question, the people who might have answered it are long gone, like mystic buildings from ages past.