The Emotional Roller Coaster At Indiana Beach

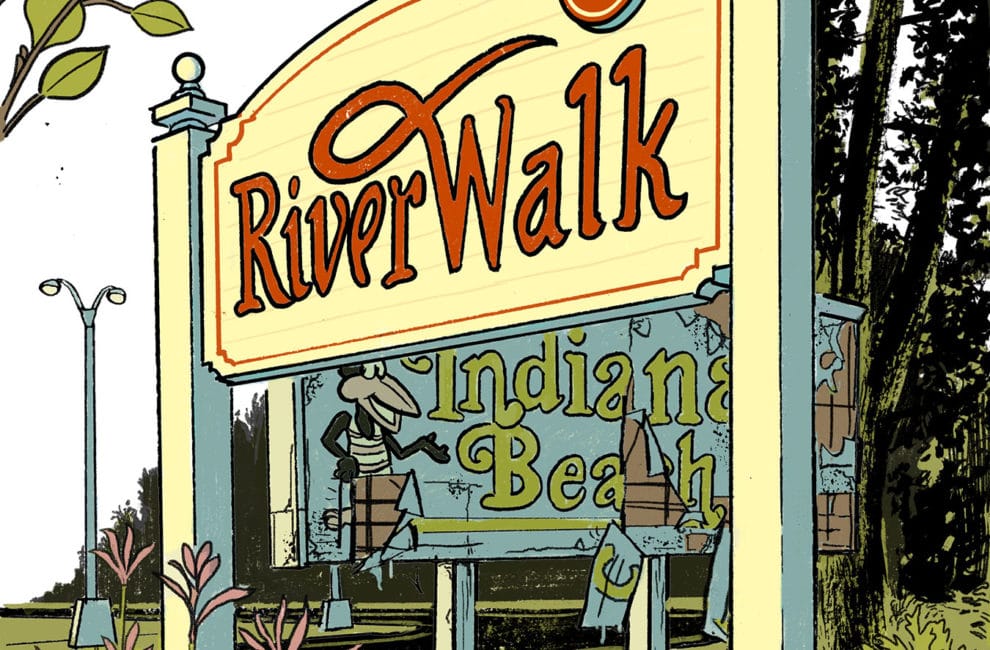

As Indiana Beach changes ownership yet again, Monticello has a plan to stay on track. Illustration by Curt Merlo

Summer without Indiana Beach would be hard to imagine for Ed and Sylvia Ward. The couple met as teenagers on the boardwalk after Ed’s shift at the bumper cars. Years later, their five children all worked at the resort. And last summer, though Ed had sworn off roller coasters—he’s 62 and has had open-heart surgery—he took two grandkids on the Lost Coaster of Superstition Mountain.

“It felt like being shaken in a paint can,” he says, laughing. “I was very glad when it was over.”

Like many people in Monticello, the Wards have warm memories of the 376-acre amusement park that juts into the Tippecanoe River: fireworks, dancing, tacos, Skee-Ball. Though they didn’t go as often in recent years, summer didn’t pass without at least one trip to Indiana Beach. So imagine their shock and sadness when they learned in February that California-based Apex Parks Group had closed the amusement park after 94 years because it could no longer make the capital improvements necessary to maintain the aging rides. Not only was the small city of Monticello about to lose its biggest attraction, the economic ripple effect could hobble everything from motels to ice cream shops there. A 2002 Purdue study—the most recent, comprehensive one—concluded that tourism pumped $60 million into the local economy.

“It was like a sock to the gut,” says Monticello mayor Cathy Gross. “It was quite a wallop.”

But fans of the Cornball Express were not going down without a fight. A Leap Day rally drew hundreds of people with heart-dotted signs. More than 53,000 supporters signed an online petition to save the park. Within weeks, county leaders offered $3 million in incentives by dipping into the White County Wind Farm Economic Development Fund, a nest egg of contributions from local wind farms earmarked for projects that improve the area’s quality of life.

“I wouldn’t expect this summer to be good no matter what happens,” says a White County commissioner.

Then, a new twist: Shortly before Apex filed for bankruptcy, Chicago businessman Gene Staples swept in and bought the park—the third owner in a dozen years. Monticello celebrated the last-minute stay of execution. For Staples, though, challenges abound. He must fix up the old rides, build new ones, and repair frayed relationships with the community. Perhaps even more dauntingly, the coronavirus crisis has all but assured his first summer as owner will be bleak.

“I wouldn’t expect this summer to be good no matter what happens,” says White County commissioner John Heimlich, “but he is in it for the long haul, which is great.”

Meanwhile, Mayor Gross and other community leaders are forging ahead on a redevelopment project they hope will keep tourists coming to White County, regardless of Indiana Beach’s future. The plan focuses on creating a river-walk district that could enliven downtown. For decades, Indiana Beach owner Tom Spackman marketed the park with a locally famous motto: “There’s more than corn in Indiana.” Now Monticello boosters are determined to prove there’s more in Monticello than Indiana Beach.

The history of Indiana Beach began with a dam and a dream. First, the dam: In 1923, the Norway Hydro Electric Plant built one 2.5 miles north of Monticello to create Lake Shafer for the purposes of energy production. Earl Spackman, a furnace salesman, bought property along the new lake and built a vacation cottage. Curious visitors often stopped to admire the water and, because the steep banks made entry precarious, asked Spackman where they could swim. That led to the dream: a sandy beach where landlocked Hoosiers could frolic in the summer. With a team of horses and workers, Spackman covered the mud flats with gravel and sand, and opened Ideal Beach, a small resort with a bath house and rental boats.

Fast as a zipline, the resort took off. In 1930, Spackman added a dance hall. Profiting from its convenient location halfway between Chicago and Indianapolis, Ideal Beach became known as “The Riviera of the Midwest” with fireworks shows, parachute jumpers, and vaudeville acts. Over the decades, famous entertainers such as Glenn Miller, Duke Ellington, The Who, and The Beach Boys made a stop there to perform.

Earl Spackman’s son Tom, who had worked at the park since age 12, took over operations after Earl passed away in 1946, and began investing in big rides like the Ferris wheel and The Bullet. Tom Spackman was a hands-on owner. When the park installed a bungee jump, he was the first to leap off—at age 85—to prove it was safe. Perhaps most importantly to the people of White County, he hired local, from teenagers to service contractors.

“Indiana Beach took care of the area,” says Jim Haworth, owner of Main Street Mall Antiques. “Tom Spackman and his family were definitely pro local business.”

Spackman was also pro-family. His daughter, Ruth Davis, and her five siblings all worked at the park. “That was where the action was, so that’s where we all wanted to be,” says Davis, who rose from hat-check girl to management. In winter, the family focused on repairs, adding something new each year, from rides to waterlines.

Tom Spackman kept admission low so it would be affordable for everyone, and the park always found a way to balance the books. But in 2008, the Spackmans’ long ride came to an end when the family voted to sell the business to New York–based Morgan Recreation Vacations. “Basically, our dad was elderly, and it was just something he felt he needed to do,” Davis says.

According to many in Monticello, Indiana Beach was never the same. Standards declined, and hefty entry fees—the daily admission price for adults rose to $39.99—discouraged locals from wandering in to people-watch. In 2015, Morgan Recreation Vacations sold the park to Apex Parks Group. (Both Morgan and Apex declined to comment.) But the destination continued to struggle. “You can’t have lived here and not seen the change,” says Mayor Gross.

One of the locals who lamented the decline, Darrell Hall, recalls how Tom Spackman, who lived to be 100, cared about local people and was personally invested in the park. “He would be out there picking up trash,” Hall says. “People thought he was a janitor. He was listening. He was watching. He was observing. When you have megabucks from the coast, on the other hand, you’re just there for the money.”

It’s a story Stephen M. Silverman, author of The Amusement Park: 900 Years of Thrills and Spills, and Dreamers and Schemers Who Built Them, knows all too well. The United States once boasted 2,000 amusement parks. Only a quarter remain. Locally owned parks were usually headed by “lovable eccentrics,” whose personal joy and commitment buoyed them through hard times. Since the roller-coaster heyday around 1910, the $20 billion amusement-park industry has been consolidated into mega-parks like Disney and Six Flags, while the small-town resorts have become white elephants.

“These companies that come in are not interested in people’s memories, in creating fantasy worlds, in nostalgia,” Silverman says. “They are interested in land value. There are more lucrative ways of getting money off the property than keeping up old mechanical rides that are costly to maintain and carry heavy insurance premiums.”

Today’s children have more options, Silverman adds, from cell phones to video games to virtual reality. Furthermore, giant corporations like Disney have the deep pockets to relentlessly innovate, dreaming up faster, scarier rides.

“The public tires easily,” he says. “How many times can you ride the Ferris wheel? You need a new adventure.”

Silverman advises theme-park owners to make sure their attractions look pristine and have fresh landscaping. Serving good food is essential, as is developing water rides, which are more lucrative than roller coasters.

Haworth, the antiques dealer, has his own priority for Indiana Beach’s new owner: Repair the relationship with the community. Locals felt dismissed when entry fees soared and they could no longer stroll inside for a couple bucks.

“PR work would be the big thing, No. 1,” says the longtime Indiana Beach goer who snuck into a Janis Joplin concert there when he was a young teen. “So much damage has been done.”

Rather than wait to see whether Gene Staples is a successful new owner, civic and business leaders in Monticello are preparing for a future that might not include the park. There’s plenty to do in White County besides Indiana Beach, they insist, and the new river walk would add to the mix.

From behind the desk at her T-shirt shop in Monticello, Keli Jennett ticks off a list of nearby attractions: lakes and water sports, wineries and brewpubs, a Pete Dye golf course, Indiana’s largest boat (the Madam Carroll), a drive-in movie theater. “The amusement park was a bonus, but not the whole draw,” says Jennett, who also owns two other local businesses, a marketing company and the Dockside Lake Resort with six rental cottages.

With or without Indiana Beach, Calvin Chambers says his family has no plans to sell their lakeside cottage, which they have owned for 40 years. “The lake is still a nice escape,” says the Zionsville resident. “In Indiana, there aren’t a whole lot of places you can go to find water.”

Local officials are banking on that allure with The Monticello RiverWalk. While many pretty houses line the Tippecanoe River that feeds Lake Shafer, there is no public river access from the city, a fact that residents have long lamented. The Monticello Redevelopment Commission plans to launch a fundraising campaign to raise $50,000 via the crowdfunding platform Patronicity. If it hits the target, the Indiana Housing and Community Development Authority would match this sum, bringing the town close to the $120,000 cost of building a plaza and a pavilion overlooking the river.

That’s just the beginning. The owner of the nearby Bell Tower Apartments has donated land for an adjacent park, which would include benches, sculptures, and cafe tables. In the coming years, the river walk could expand with a series of add-on projects such as fishing piers. An added bonus: Establishing such a district would allow the city to offer more liquor licenses, which could entice more restaurants to open.

Mayor Gross thinks a lively riverfront will kickstart development downtown. “We believe if we build it, they will come,” she says. “I want to make this amazing environmental resource accessible to everyone, whether they can afford lakefront property or not.”

Dan Oldenkamp, who heads up the Monticello Redevelopment Commission, envisions “swipe and go” kayak rentals along the river walk. People could paddle for a while, stop for lunch, and shop. “How big could it be?” Oldenkamp says. “We have some big thinkers. The economic impact could be millions, but we just don’t know yet.”

That may sound ambitious for a project that, as of press time, hadn’t even raised $50,000 in startup funding. But Gross says that Monticello has always been resilient. The city survived a tornado in 1974 that decimated the community. It survived a loss of industry and manufacturing in the 1980s. With or without the Steel Hawg, she insists they’re on solid ground.

Gross learned Apex was planning to close Indiana Beach right after leaving a presentation about the river walk this winter. She sees the timing as fortuitous—a reminder that the city can’t rely on its historic amusement park forever.

“What this tells me is that we’re on the right track,” she says. “Kick it into overdrive and get it done.”