King of the Kill: An Excerpt of Frank Bill's New Novel, Donnybrook

A few years ago, some writerly friends of mine passed around the short stories of an obscure author from the sticks of Southern Indiana, as if his prose were a smoldering joint. So, like most illicit pleasures, the fiction of Frank Bill came to me with a wink and a nod. “Try it,” they said. “You’re gonna like it.” They were right. Bill’s words, protagonists, and endings were blunt, cruel, and dark. As a Southern Indiana boy myself (who stuck mostly to town), I’d always had a healthy fear of—and fascination with—the dimly lit trailer park, the hog farms’ blood-curdling squeals, and the secrets held by junked cars in gnarled hardwood forests. The jagged pieces in Bill’s 2011 collection of short stories, Crimes in Southern Indiana, provided a cracked window into these and similar venues, best read with one eye on the text and the other on the door.

Something was bound to go wrong—and it always did. In literature, the term is “Chekhov’s gun,” a dramatist’s rule of foreshadowing. It means if the writer devises a gun—metaphorical or otherwise—at the beginning of a story or play, it must go off by the end. But in Bill’s “grit lit,” as the genre is known, I’ve learned there’s a corollary to the principle: Yes, the gun must go off (and it will, frequently), but when it does, neither the target nor the shooter is safe. Bad decisions have bad consequences. Ultimately we, the readers, are the collateral damage—hearts soured by unnatural men (and women) who commit damning acts we know come far too naturally.

Now hailed as a hayseed Tarantino or a latter-day Steinbeck, Bill, a 39-year-old native and resident of Corydon, began his writing career across the Ohio River in Louisville, as a forklift driver in a paint-additive factory. Self-taught, he spent his downtime scribbling in a notebook, sketching desperate tales culled from the plight of real-life family members, friends, and twangy bogeymen. Born was Crimes, a work featured in Playboy and praised by GQ.

The following passage is excerpted from Bill’s forthcoming first novel, Donnybrook, due out this month and heralded by publisher Farrar, Straus and Giroux as “a nightmare vision of the American Heartland.” Try it. You’re gonna like it. Wink. Nod.

—Michael Rubino

EXCERPT: DONNYBROOK

I can’t feed my babies, Zeek and Caleb, from jail, Jarhead Earl thought. But this was his chance to give them a better life

He thumbed two more 12-gauge slugs into the shotgun’s chamber.

The click of the first slug had echoed in Dote Conrad’s ears after he’d handed the 12-gauge automatic with a full choke to Jarhead.

The barrel raised, Jarhead said, “Put your hands high. Turn to me, slow.”

Dote could’ve grabbed any one of the rifles or shotguns that lined the wall in front of him behind the counter of his gun shop. But none were loaded.

He raised his hairy appendages. Spread them like a football field’s goalposts.

Hands level with his ears poking out of his brown trucker’s cap, faded rebel flag across the front. He wore a gray T-shirt. Red suspenders going down over his keg belly. Brass clips pinched the waistband of his camo pants. Said, “We got layaway if you can’t

buy it today. Deer season’s still a ways off.”

Jarhead said, “I ain’t buying shit. You walk to the end of the counter. I’ll follow you to the safe in back. ’Less you got enough in the register.”

Everyone in Hazard knew Dote only deposited his sales once a month. Kept a safe and register packed with big bills. Had never kept a loaded pistol behind the counter for personal protection. There was never a need to worry about being robbed in a small-town gun shop out in the hills of southeastern Kentucky where, after first grade, everyone knew who they’d marry and have kids with.

Dote tried, “Know times is tough. People out of work with the economy bein’ in a slump. Hear the state be hiring for the road crews real soon. Whatever it is you don’t have ain’t gonna be got by doin’ whatever it is you plan on doin’ with that shotgun.”

Zeek and Caleb’s grit-smeared faces branded Jarhead’s mind with their whining—I’s hungry, Dada. He didn’t have time for Dote’s recommendations. “Let’s see what you got in the register first.”

“Jarhead, I can’t—”

Jarhead veered the barrel two feet away from Dote. Blew a hole in the wall. The shell hit the counter. Another fell into place. Dote’s ears rang as he reached for the gun barrel. Jarhead pushed into the counter. Butted the hot barrel through Dote’s hands. Stabbed it into Dote’s coral nose like a spear. Cartilage popped. Dote hollered, “Shit!” Tears fell from his blinking eyes.

Jarhead said, “I ain’t asking.”

Dote bent away from the barrel. His camo pants went dark in the crotch. Loose skin hanging from his arms wavered. Sweat creased the age spots of his forehead. He felt weak and idiotic, knowing that if he had a gun, he’d shoot this thieving bastard. He waddled to the register, cursing to himself, who’d have thought he’d bring his own goddamned ammo. Punching a few buttons, he opened it with one hand while the other pinched his nose. Pulled a wad of twenties from the tray. Then a wad of tens and fives. Laid them on the glass counter.

Jarhead ordered, “Count it so I can hear you.”

When Dote counted out one thousand dollars, Jarhead shouted, “Stop!”

Half a stack of twenties remained. Dote spoke through his clogged nose. “You don’t want it all?”

“Don’t need it all.” Held the shotgun one-handed. Reached into his back pocket. Laid a plastic Walmart sack on the counter. “Put the one thousand in the sack.”

Dote stuffed the money into the sack. Blood from his busted nose dotted the bills he pushed to Jarhead, who grabbed the sack, said, “Lace your fingers behind your head. Back up. Turn around. Go into the back room.”

The thought of never seeing his wife, who ate fried chicken livers breaded with her mother’s secret recipe and watched the Home Shopping Network on satellite while he ran the gun shop, sent a shock of worry through Dote’s body. And he pleaded, “Come on now, wait!”

Jarhead motioned the gun barrel. “Turn around!” Dote did. Walked sideways to the counter’s end, where Jarhead met the rear

of his head. Pressed the barrel into it. Walked Dote through the curtain into the back room, where boxes of ammunition were stacked among crates of unopened rifles. Here was the fucking ammo he needed and Jarhead told him, “Get on your knees.”

Dote’s face warmed with tears. Clear mucus mixed with blood.

“Please!” he begged. “Please!”

His knees cracked down onto the cold, hard concrete floor. Jarhead followed him with the still-warm barrel of the gun. Touched the rear of Dote’s skull. Then Dote fell forward from the loud shudder that rippled through his body.

Red and blue lights lit up the rear window of the primered Ford Galaxy. Next to Jarhead sat the Walmart sack of cash. Socks. Underwear. Cutoff jeans and a T-shirt rolled up inside also. Across the passenger’s seat lay the map a fighter who went by the name Combine Elder had detailed for Jarhead. Directions to the Donnybrook.

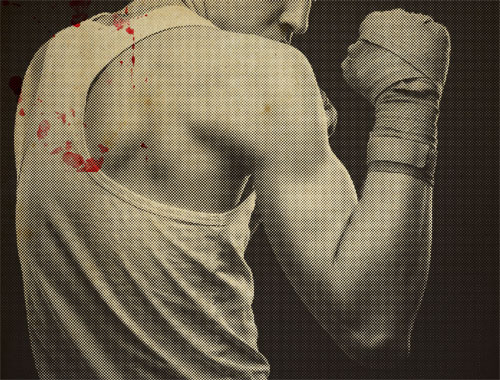

Jarhead’d learned about Donnybrook two nights ago, after he’d beaten Combine Elder into twelve unknown shades of purple. Afterward, Combine had smirked at the unblemished rawhide outline and wheat-tinted hair of Jarhead Earl, his razor-tight arms clawed by black and red amateur tattoos hanging by his sides. Combine told him, “Son, you oughta enter Donnybrook. You could be the next Ali Squires.”

Ali Squires: Bare. Knuckle. God.

Squires was beaten only once, by a man went by Chainsaw Angus.

His knees cracked down onto the cold, hard concrete floor. Jarhead followed him with the still-warm barrel of the gun. Touched the rear of Dote’s skull.

Combine told Jarhead that Donnybrook was a three-day bare-knuckles tournament, held once a year every August. Run by the sadistic and rich-as-fuck Bellmont McGill on a thousand-acre plot out in the sticks. Twenty fighters entered a fence-wire ring. Fought till one man was left standing. Hordes of onlookers—men and women who used drugs and booze, wagered and grilled food—watched the fighting. Two fights Friday. Four Saturday. The six winners fought Sunday for one hundred grand.

The two jobs Jarhead worked, towing for a junkyard during the day, then flipping burgers and waffles two or three nights a week, hardly provided enough cash to feed and clothe his two smiling-eyed progeny. Boys created with the comeliest female in the Kentucky hills, Tammy Charles.

In between his jobs he jogged through the mining hills that gave his stepfather black lung and his mother gunpowder suicide. He pounded the homemade heavy bag that hung from a tree in front of his trailer till his hands burned red. Training for his next bare-knuckle payday out in an abandoned barn or tavern parking lot. Farmers. Miners. Loggers. Drunks. Wagering on another man’s will.

Altogether, the money he was making came nowhere close to one hundred grand.

Donnybrook would be Jarhead’s escape from the poverty that had whittled his family down to names in the town obituaries. He just needed the thousand-dollar fighter’s fee to enter.

Jarhead pulled to a stop off the side of a back road somewhere outside of Frankfort, worry from the robbery tensing his hands damp on the steering wheel.

The cruiser’s door opened. The outline of the county cop approached. Jarhead had his window rolled down. Watched the shadow trail toward his car in the rearview. The officer stopped at his window.

Should I open the door, punch him in his throat, his temple? Can’t get caught if I’m going to help my babies and my girl, thought Jarhead.

And the officer said, “Evening. Know you got a busted taillight?”

Shit! rang through Jarhead’s bones. All that worry for nothing.

Smiling, sweating, Jarhead said, “Why, no, sir. I sure didn’t. Which side might it be?”

Pointing, the officer said, “Right back on your passenger’s side.”

“Well, I’ll be having to get that fixed shortly.”

“Can I see your license and registration?”

“Sure, sure.”

Jarhead pulled his license from his wallet. Registration from his glove compartment. Handed them over.

Officer took them. Read over the name. Address. Said, “Long ways from home, ain’t you, Johnny. Taking a trip?”

“Yeah. Going to visit friends and family up in Indiana.”

“What part of Indiana?”

Nosy. “Down over in Orange County.”

“The southern part. I got kin down in that neck of the woods myself. Who’s your people? Might be some acquaintance.”

This is how they catch sons a bitches, Jarhead thought. Hare-brained coincidences. He told the only name he could think, one that Combine Elder told him. “McGill. Bellmont McGill.”

The officer parted a big rabbit-toothed smile, said, “Yeah, I remember old McGill. Owns damn near half of Orange County since his in-laws passed. Lots say he’s rougher than a cob. Never had no cross words with him. He’s tough. Not one you’d cross. Other than that, seems a fair shake. That your daddy’s side or your mamma’s?”

Son of a bitch must be writing an oratory on hill country families. “My daddy’s.”

Officer’s face went odd. “Daddy’s? I don’t recollect McGill having brothers, nor uncles. His parents was only children, like he. How you related to—” That’s when the radio on the officer’s side dragged static. Came across with an all-points bulletin. “All units be advised of a black-primered Ford Galaxy. Plate number—”

Jarhead slammed his door into the officer’s knees. Got out. Left-right-left-punched him to the ground while his radio spit, “Suspect Johnny Earl is considered armed and dangerous. Wanted for armed robbery in Hazard, Kentucky.”

Jarhead rolled the officer facedown. Thumbed the snap open on the officer’s leather cuff holder. Pulled the handcuffs

out and cuffed his wrists behind his back.

Jarhead grabbed his license and registration. Stuffed them down into his pocket. Dragged the cop to his cruiser. Popped the trunk from inside the car and heaved him inside. Closed it. Drove the cruiser out into the woods away from the road. Killed the flashing lights. Tossed the keys into the front seat.

He’d made it back to his Ford Galaxy when a set of headlights came down the road. Blinded him. Stopped. A thick-bearded man sat inside an old International truck with the radio blaring—“It’s All Good” by Seasick Steve. The man looked at Jarhead through the rolled-down window, asked, “Everything all right, buddy?”

Jarhead reached into his car. Grabbed his map, the Walmart sack, and said, smiling, “No, it’s not. I’s having some car troubles. Believe she’s seen her last mile. Think I could get a lift?”

The man shook his head, said, “Why sure.”

Jarhead got in. Strong waft of fuel burned his eyes. The man shifted into gear. Then offered a hand. “Tig Stanley. Don’t mind the gas smell. Just doing a few nightly runs.”

Jarhead shook his hand, said, “Fine by me. Name’s Johnny Earl. But you can call me Jarhead.”

Tig ground the gears. Asked, “Where you headed, Jarhead?”

“Orange County, Indiana.”

Tig smiled. “It’s your lucky night, son. I can get you to Brandenburg, where my cousin runs our business. They’s a bridge’ll take you over the Ohio River on 135 into Mauckport, Indiana. From there it’s about forty-five minutes or better to Orange County. But I still got a few more stops to make. You give me a hand, I can pay you, get you to Orange County in a day or two.”

“Fine by me long as I make it by Friday. Type of work you do this time of night out here in the boonies?”

Tig pulled a plastic puck of Kodiak from his dash. Tapped it on the steering wheel. Opened it. Pinched a chew into his lip. His eyes lit up, and he said, “You’ll see.”

When Jarhead saw a light come on inside the house, he cursed under his breath. He stood out in the country road by Tig’s truck with the cloak of night all around, the truck running with the lights off. This was the fifth and final house.

A full moon guided Jarhead’s quick jaunt up the drive. He watched each room of the house come to life with light, the shadow inside bouncing from room to room. Jarhead’s heart raced, him hoping he’d make it to Tig before the shadow did.

Out back of the house a dog barked. Sounded like it weighed two hundred pounds.

Tig lay under the rear of the truck. Gas container. Small hose. Handheld, battery-powered drill. Maglite. Gas being siphoned from the tank and into the red container. Tig and his cousin would sell it for a cheaper price than was paid at the pump.

The creak of the door went unheard. Light footsteps across the wooden deck. Down the steps. Into the dew-covered grass. A single-barrel 20-gauge lifted the same time Tig stood up. He heard the click and then the voice. “You thieving piece of—”

From behind, Jarhead wrapped a sleeper choke on the man with the shotgun. But not quick enough. An explosion lit up the dark, hollowed everyone’s eardrums. Lead dinged against the truck. Shattered the driver’s side window.

The barking dog went psychotic behind the house, whining and howling.

The man dropped the gun. Tried to stomp Jarhead’s boot with a bare foot. Reached for the arms around his neck. Scratched and dug into Jarhead’s forearms. Jarhead held tight. The fight slowed. The man went limp. Jarhead let him fall to the ground. Stepped across the yard over to the truck. Found Tig pushed up against the back tire. Moonlight beat down on his shaking body. “Goddamn that was a rush,” Tig huffed.

Dark moisture ran from Tig’s leg. Jarhead sucked air, said, “Looks like you got hit.”

“Can’t feel shit,” Tig grunted, offering a hand to Jarhead. “Pull me up. Let’s push some back road ’fore the shit gets too deep for wading.”

Behind Jarhead, the house door opened. A woman’s voice screamed back into the house, “Sarah! Sarah! Dial the county police.

They’s men out here done shot your daddy! They stealing his truck!”

Took Tig’s hand and pulled him to his feet. Reached for the gas containers. Tig said, “Give me one them sons a bitches, boy.” Jarhead helped Tig across the yard, each weighted down with a container in tow, half running toward the road where the truck sat idling. Tig laughed. “Ain’t this fun?”

The lady barefooted across the deck. Down into the yard. Found her husband while her daughter rang the police. “No!” the lady screamed. Started off behind the house. Kneeled down at the maniac dog. Said, “Grim, calm your ass down.” Unlatched the heavy chain. Said, “Now these sons a bitches gonna get theirs.”

Jarhead was restless and a bit worried. He hadn’t beat on a bag since the robbery. He needed to expand his lungs. Feel some flesh give.

At the truck, Tig slung the gas into the rear. Out of breath, he told Jarhead, “You gotta drive. My leg is burgered.”

Jarhead said, “All right.” Opened the passenger’s side door. Heard steps pushing through the damp yard. Then a low growl followed by the lightning-fast roar.

Tig hollered. Fell against the truck’s bed. Tried to kick. Punched and pushed at the black German shepherd that came up on its hinds. Laid its fronts on his chest, its mouth gnawing into his right arm.

“Get this bastard off me!” He shrieked like a teething child.

With no gun, knife, or makeshift billy club, Jarhead did the only thing he knew to do. Balled his fist and punched the mauling shepherd in its head. Grim yelped, fell, and ran.

Tig lay against the truck, breathing heavily. Moisture running now from his leg and arm, smearing the side of the truck. He panted, “You about a mean son of a buck. Gonna have to buy you a few rounds.”

Jarhead helped Tig into the passenger’s side. Told him, “Don’t owe me shit.” Slammed the truck’s door. Heard the sirens coming from afar. Got in on the driver’s side.

Asked Tig, “The hell you want me to go?”

Fuel rimmed Tig’s hands and clothing, combined with the red that seeped from his peppered wounds. He laughed. “Get me to my cousin’s. He take care of me. Pay you good.”

“Just give me some damn directions. Got no idea where I’s at.”

Tig said, “Keep going down this road heading west till you see the signs for Brandenburg. Follow them.”

Jarhead stomped the gas just as the road behind him lit up.

Cans of gasoline surrounded Jarhead. He ran one hand through his sweaty locks. Thought about those lights from a few nights back. The truck’s gas pedal to the floor. The red-and-blue flashes that had opened the night. He took the back-road curves not knowing his way. But outrunning them.

Now, Jarhead stood in a rusted tin garage, a grease-smudged rotary phone held to his ear, thumbing a creased and worn picture of Tammy and the boys. He hadn’t spoken to them in days, missed the boys watching him skip rope in the dirt yard and work the heavy bag in the late evenings. They’d clap their tiny hands in amusement. After training he bathed them and tucked them into bed for sleep. Showered, then went into his bedroom, wrapped his arms around Tammy’s warm innocence.

He’d needed to let Tammy know he was okay. Make sure she and the boys were the same. Into the phone he asked, “Anyone hassle you?”

The female voice was feather-pillow-soft with worry. “Marshal Pike just wanted to know if I’d seen or heard from you. Wondered why you’d go and rob a gun shop for one grand. Not take a penny more and leave the shotgun.”

“What’d you tell him?” Jarhead asked.

Tammy said, “Last I seen you the sun was rising. The kids was crying with shitty diapers.”

Jarhead was restless and a bit worried. He hadn’t beat on a bag nor run for conditioning since the robbery. He needed to expand his lungs. Feel some flesh give. Bring some hurt. He needed to make some tracks toward Orange County. And he wasn’t real comfortable with what had happened a few nights back. Worried about the county officer he’d beat, the man he’d choked out, the cops he’d outrun. What if they’d gotten the plate number of the truck he’d fled the scene in with Tig? He told Tammy, “It’ll be over soon.”

Tammy asked, “Promise?”

“Promise. After this coming weekend I be the winner of the Donnybrook. I’ll send someone for you and the babies.”

Tig and his cousin had given him a place to rest his head, a spare room with a cot and soured sheets. In the night Jarhead heard a lot of men coming and going from the basement. But he ignored whatever it was they did besides siphoning fuel. They were his transportation to Orange County this evening.

“Why not you?” Tammy asked.

Jarhead told her, “Can’t risk being seen in or near Hazard after what I done did. I win, none of that’ll matter no way. Be more money than either of us ever did see in our lives.”

Tammy got quiet. A child sneezed in the background. She asked, “What if you don’t win? What if they’s someone meaner and tougher than you? Then what we gonna do?”

There was always a what if?. Like the first time Jarhead threw a punch. What if that man hadn’t seen him do it? Knock that other boy silly for bullying another. What if he’d not seen something in Jarhead? Taken him under his wing. Learned him how to fight. Throw a punch. An elbow. A knee. How to work his hips. Rotate and turn a fist. Where to hit and how to hit. The kidneys. The liver. Heart. How to take care of his body. Be confident, not cocky, like the man he’d never known. His real father. A marine who’d served in the Vietnam war and boxed in Puerto Rico. The man that his mother had nicknamed him after. She told him she’d left Miles before Johnny was born. That his real father, Miles Knox, spoke with the dead. Had a violent streak and a hankering for the bourbon. His mother had given him her maiden name, not his father’s.

Johnny often wondered if Miles was alive or had passed away. He’d never tried to make contact. His mother had confessed all of this to him just days before the dark cloud hit and she’d committed suicide after his stepdaddy had passed from black lung.

“Honey,” he said, “they is always someone meaner. But the smart fighter is the better fighter. I’ll win. I’ve no other choice. Then I’ll send someone for you.”

Tammy questioned once more, “You promise?”

“I done told that I did.”

“Wanna hear you say it again.”

The gloom in Tammy’s tone was killing him. He had to stay focused on their future, not her uncertain sadness.

“Promise.”

Excerpted from DONNYBROOK: A Novel by Frank Bill, published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Copyright © 2013 by Frank Bill. All rights reserved.

Photo of Frank Bill by Tony Valainis

This excerpt appeared in the March 2013 issue.