Fair Play That Changed the Face of the NCAA

Editor’s Note, Nov. 12, 2012: At tonight’s game, Indiana University and its men’s basketball team honor Bill Garrett, the first African-American man to play Big Ten basketball, marking the 65th anniversary of the first game in the conference in which he played.

“Well, what happens now to Bill Garrett, Emerson Johnson and Marshall Murray? After the medals and trophies have been stored away, what then? Was it all just moonglow? Was all the celebrating merely a moment of brotherhood in an eternity of intolerance?” —The Indianapolis Recorder, April 12, 1947

FOREWORD

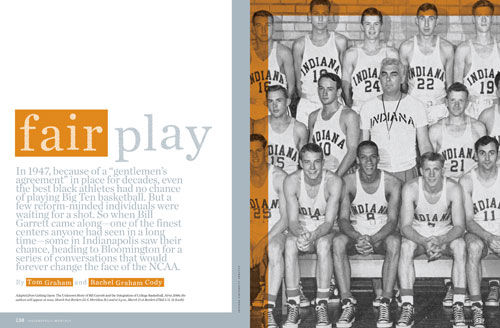

Bill Garrett was Indiana’s Mr. Basketball for 1947, a good student and a great kid. His high school team, the Shelbyville Golden Bears—the first in Indiana to start three black players—had won the state championship in dramatic fashion, and for a week afterward, sportswriters all agreed that “Bill Garrett of Shelbyville was the classiest individual player ever to appear on an Indiana high school floor,” and that “such amazing accuracy, blinding speed and sheer determination [were] never exhibited to a higher degree than … by Bill Garrett, Shelbyville’s great Negro all-star.” In June he led the Indiana All-Stars to a decisive win in the Indiana-Kentucky All-Star Game.

But no one offered Garrett a college scholarship. Oniy a few blacks, mostly in the New York and Los Angeles areas, had ever played major college basketball. Indiana University had never had a black basketball player, nor had Purdue, Notre Dame, Butler or any of the other nearby major basketball schools. It was an open secret that Big Ten coaches had a gentlemen’s agreement barring blacks from basketball. Indiana was the top source of high school basketball talent for the whole country, but college coaches, scouring the state for recruits, ignored the state’s top player.

tried and failed to interest college coaches in Bill Garrett: no one wanted to be first. By summer, Garrett, Barnes and Kaufman had given up on Purdue, IU and other major universities. Garrett was hauling trash in Shelbyville and getting ready to attend Tennessee A&I State in Nashville, a historically black school with strong athletic and academic traditions.

But a giant had been watching. Faburn DeFrantz, the executive director of lndianapolis’ Senate Avenue YMCA—the largest black Y in the world—was convinced sports could be a wedge for opening doors to greater opportunities for black Americans. In the same summer that Jackie Robinson was integrating Major League Baseball, DeFrantz was determined to break the Big Ten’s gentlemen’s agreement in basketball, with Bill Garrett. DeFrantz had tried the previous year to break the Big Ten color line with Johnny Wilson, Indiana’s 1946 Mr. Basketball. DeFrantz met with IU president Herman B Wells, who had called in coach Branch McCracken and told him any player who was good enough must be allowed to play. A few weeks later, McCracken told an Anderson audience, in Wilson’s presence, that Wilson was not good enough to make his team.

It was a bitter experience. DeFrantz had learned from it, and he was determined not to let it happen again.

On a Saturday morning in the late summer of 1947, Faburn DeFrantz was driving south. DeFrantz had slipped out of the capital early, leaving his home on Indiana Avenue as nightlife on the Avenue was falling silent and the city was coming awake. Despite the hour, the humidity was already oppressive, and it sat on DeFrantz and his four companions like a sullen, sweaty child. The open windows of DeFrantz’ sedan provided little relief, just more hot air and the cicadas’ steady buzz. The men’s suit jackets were neatly laid out in the trunk, ties folded in the pockets. Their sleeves were rolled up and their shirt collars open a button or two, exposing their necks to the rare bits of breeze.

When DeFrantz had called them two days earlier, the men had known this would be their uniform for the trip, so they had set about making sure their Sunday suits were ready by Saturday morning. DeFrantz favored three-piece suits and insisted on a sense of decorum for even the most ordinary occasions, and today was far from ordinary. On the phone Thursday night, he had told each of his companions, “I’m going down to IU to see if we can do anything about getting Bill Garrett on the basketball team.”

Life had outlined Faburn DeFrantz in bold. He was so fairskinned that his friends jokingly prodded him to take off his hat and show his curly hair, lest he be mistaken for white. Sixty-one years old, well over six feet tall and solidly built, DeFrantz seemed to tower over everyone around him. It was, a friend said, as if Faburn was always in the foreground, and everyone else a step or two back. His wife called him “Fay,” but to just about every other black person in Indianapolis he was “Chief.”

He was born in Topeka, a child of “the Exodusters”—thousands of blacks his father, Alonzo, had helped lead out of the post-Reconstruction South to the relative freedom of Kansas. Alonzo, a deeply religious man, instilled in his children a commitment to help black Americans and a willingness to stand up for them no matter what the cost. Taking his father’s lessons to heart, DeFrantz chose his fights and did not back down. When the Ku Klux Klan announced its intention to parade down Indiana Avenue in the early 1920s, DeFrantz told the city’s mayor he would have men stationed on every street corner ready to cause “real trouble” at the first sign of a white sheet. The Klansmen marched, but without the anonymity of their sheets and under DeFrantz’ withering stare. When a supervisor at the Commons Cafeteria in Indiana University’s Union Building tried to steer DeFrantz to a table marked “Reserved” and set aside for blacks, he thundered, “I don’t want this kind of hospitality. I haven’t ordered any table reserved. This table must be for somebody else!” and instead chose a table in the middle of the room. When a visiting fan shouted, “Get that nigger!” every time Indiana’s Archie Harris had the ball during a football game between IU and Texas A&M, DeFrantz had loudly compared the man to an ugly dog and encouraged a companion to toss a cigar butt at the back of the man’s neck. A friend of DeFrantz, visiting from Texas, was certain they were about to be lynched, but in the end, it was the Texan and his companions who skulked out of the stadium before game’s end.

By 1947, DeFrantz had been Executive Director of the Senate Avenue YMCA for 31 years, and the line between man and institution had long since blurred. Under his leadership, the Y had grown from a handful of members leading Boy Scouts and Bible classes in 1916 into the largest black YMCA in the world and the social, political and cultural heart of black Indianapolis. By the 1940s, the Y—a three-story brick building at the corner of Senate Avenue and Michigan Street—offered more classes and clubs than most large high schools and many colleges. Y members provided job placement services, relief programs, support in juvenile court and college counseling. The Y’s dorm housed traveling orchestras, destitute men, and visiting black athletes and entertainers who were barred from Indianapolis’ white hotels. In 1947, more than 110,000 people used the Y, an average of 300 a day 365 days a year.

The Y’s showcase was its annual lecture series, the “Monster Meetings,” whose name parodied the weekly “Big Meetings” held at Indianapolis’ all-white Central YMCA. DeFrantz had developed the series from a thumping pulpit for local preachers into the longest-running, best-attended and most prestigious black public forum in the country. The lectures ran Monday nights from November through March and—reflecting DeFrantz’ belief that all areas of life concerned the black community, not merely politics or the “race question”—the speakers were a who’s who of black America in the 20th century: from W.E.B. DuBois to Langston Hughes, from Jackie Robinson to the scholar E. Franklin Frazier. Thousands attended, mostly black men but also a handful of whites and, on special occasions, women of both races. The Y’s gym was always crammed full with an overflow crowd often standing shoulder-to-shoulder in the lobby and listening via loudspeakers. And when the Y couldn’t hold them all, as when Eleanor Roosevelt or Martin Luther King Jr. visited, the meetings were held in larger facilities such as the Indianapolis Murat Temple or Cadle Tabernacle.

It was at the Monster Meetings that the idea of a campaign to integrate Indiana University basketball was first raised in earnest. The local community needed a sign of change and a symbol of hope, for the dispiriting post-war conditions of blacks across the country were especially acute in Indiana. In 1947, Indianapolis had pervasive segregation, one of the highest unemployment rates in the country for black men, and some of the worst housing conditions for blacks of any northern city. In Indianapolis, almost half of all black veterans and their families were doubling up with relatives in cramped homes or were living in trailers, rundown hotel rooms or tourist cabins; and there was no sign of housing relief in sight. A few loosely organized sit-ins had made some headway toward integrating the city’s cafes and soda fountains, but at least one drugstore chain had fired all of its black employees in Indianapolis in retaliation. The Indianapolis police chief had recently declined to issue a permit for a dance at the Antlers Hotel downtown because the event would be integrated. Asked what policy he was enforcing, the chief had said, “My policy.” Refusing to overrule the police chief, Mayor Robert Tyndall told the dance’s sponsors, “My administration has been marked by good race relations, and I don’t intend to see this record marred.”

Against this bleak backdrop, DeFrantz and others at the Senate Avenue Y saw the integration of IU basketball as a ripe target for scoring a public victory and giving some hope. Along with black leaders across the nation, they were watching as Jackie Robinson made history with the Brooklyn Dodgers in the spring of l947, and they were also watching something else: Side-by-side with stories of Jackie Robinson in the country’s black press—and overshadowing Robinson in The Indianapolis Recorder—were stories of integrated Shelbyville’s state championship and of Indiana’s 1947 Mr. Basketball, Bill Garrett. DeFrantz and his friends saw a golden opportunity for a Hoosier Jackie Robinson in the sport that dominated the state of Indiana.

McCracken, the big, intimidating “Sheriff,” had coached IU to the NCAA championship in 1940, securing his place as the symbol of Indiana basketball and his reputation as a successful and innovative coach. But McCracken had steadfastly ignored Indiana’s talented black basketball players. Just the year before, when McCracken returned to IU after a stint in the Army Air Corps to find the basketball program in desperate need of rebuilding, DeFrantz had tried to interest the coach in the state’s best high school player, Johnny Wilson, who, like Garrett, had been named Mr. Basketball for 1946, and led his integrated Anderson High School team to the state championship. Wilson wanted to play at IU, and DeFrantz, meeting with Herman Wells less than 24 hours after the 1946 state championship game, had received an assurance from the IU president that the only standard for joining the university’s basketball program was whether a young man could play well enough.

But a short time later, McCracken, seizing the letter of Wells’ promise if not the spirit, had looked over Johnny Wilson’s head and told a questioner at an Anderson victory banquet that Wilson was not a good enough player to make his team.

DeFrantz had learned from the experience. For this year’s journey he had drafted a team consisting of his assistant, Hobson Ziegler, Indianapolis attorneys and IU graduates Rufus Kuykendall and Everett Hall, and AI Spurlock, a teacher at Crispus Attucks High School. DeFrantz brought this larger group to serve as witnesses and to pose an unspoken threat—of potential lawsuits and controversial publicity—should IU again refuse to integrate basketball. Together, the five headed south toward Bloomington to confront Herman Wells and get their answer.

Herman Wells was a perfect match for Faburn DeFrantz but a curious fit for his hidebound state. Five feet seven, 310 pounds, gregarious and suave, he looked like Santa Claus’ urbane younger brother with a trim mustache instead of a beard. His appetites were gargantuan and his tastes eclectic, running from thick chicken gravy and fresh catfish to antiques, opera and the best French wines. Wearing custom-made suits and the occasional coonskin cap, Wells tooled around Bloomington at racing speeds in his sky-blue Buick convertible.

A lifelong bachelor who called IU his “mistress” and the students “my children,” the president scheduled meetings at times that enabled him to cross the campus just as classes let out, so he would see as many students as possible, many of whom called him by his first name. He held open office hours every week, when students could drop in to discuss everything from coursework to their love lives. He liked to tell of a student who breezed into his office early in his presidency and announced, “You’re too fat, Hermie. Give me two evenings a week and I’ll train 70 pounds off you.”Wells would spend a lifetime fighting a losing battle against his ever-expanding waistline—what he called “my misshapenness”—often joking, “Diets are easy; I’ve lost over 600 pounds on them.”

But he had been dismissed as a lightweight, a temporary place-holder, when he agreed to be IU’s acting president in June 1937. He was 34 years old, lacked a doctorate and had been dean of the IU Business School for only two years. Even so, Wells never considered himself “acting” anything. He seized the reins of IU with such authority that within a year the Board removed the qualifier from his title, making Wells, at 35, the youngest university president in the country.

Wells quickly set about waking IU from years of sleepy complacency and transforming it into a nationally recognized institution, recruiting top-notch professors, overseeing the rise of IU’s world-famous music school, expanding foreign-language and international programs, tripling the size of the campus while protecting its trees, and vigorously defending academic freedom—most famously that of IU zoologist and sex researcher Alfred Kinsey. He did these things even though Indiana, in the 1940s, was stone-cold isolationist, suspicious of foreigners and resistant to change.

Wells regularly took flak for being too permissive and too radical, but the IU president knew his state. An Indiana native and IU graduate, he had been field secretary for the Indiana Bankers Association at the height of the Depression, when banks were failing and farms were being foreclosed on in large numbers. Wells traveled often to all of Indiana’s 92 counties, talking survival with community leaders and farmers—and keeping card files on all of them, noting spouses, children, secretaries, and sometimes even menus and flower arrangements, a practice he maintained all his life.

“I doubt anyone realized a policy had been changed,” Wells wrote later. He squelched red-baiting at IU by telling the American Legion he would be happy to accommodate its demand for an investigation of communists among the IU faculty—if only the Legion would first show him evidence they existed. To those who urged him to be more confrontational, Wells had a reply: “I want to win every battle, and not lose one.”

In the summer of 1947, Wells was worried about two impending controversies: one over Alfred Kinsey, who was preparing to publish The Kinsey Report on Sexual Behavior in the Human Male, and the other over segregation at IU. At the time, IU had only a couple hundred black students among a student population of over 12,000. They were barred from the dorms and most campus dining halls, honorary societies and university social events, from the barbershop in the Union Building, from white fraternities and sororities and most Bloomington restaurants. Black student teachers could not do their practice teaching in the segregated Bloomington schools, and instead had to travel 50 miles north to Indianapolis. Black men were barred from IU’s otherwise compulsory ROTC program by a local doctor’s blanket diagnosis that they all had flat feet, and every year the university admitted no more than 84 black women—the number of off-campus rooms available for them.

Integration of the IU campus had long been one of Wells’ top priorities. His first student-assistant, a black zoology major named John Stewart, had helped Wells understand the extent and effects of campus segregation. Only six years younger than Wells, Stewart would become one of the president’s closest friends, reporting to him on IU’s “blind spots.” Wells had once told a carefully selected audience, “We must prepare to renounce prejudice of color, class and race. Where? In England? In China? In Palestine? No! We must renounce prejudice of color, class and race in Bloomington, Monroe County, Indiana.”

Wells worked to integrate the IU campus the same way he approached other innovations: with subtlety and finesse. If critics tried to speak in racist code, Wells stole their veneer of respectability by feigning incomprehension, forcing them to make a crude statement or else keep quiet. Once his discreet changes became faits accompli, few ever challenged them. “In taking the steps required to remove those reprehensible, discriminatory rules,” Wells later wrote in his autobiography, “we tried to make a move, if possible, when the issue was not being violently discussed pro and con on the campus. I felt that making moves in this manner would, and in fact it did, prevent any backlash that might set the whole program back.”

But stealth and charm had not been enough to budge IU’s biggest racial barriers—the women’s dorms, practice teaching, ROTC and basketball. For years Wells had been worried about Missouri ex. Rei Gaines v. Canada, a 1938 U.S. Supreme Court decision requiring the University of Missouri Law School to admit a qualified black applicant. Gaines, a forerunner of Brown v. Board of Education, increased the risk that state universities would be sued over segregation. Soon after the decision, Wells asked IU’s legal counsel, George Henley, to review the university’s vulnerability to lawsuits in light of Gaines and after receiving Henley’s report, Wells followed up by asking specifically about blacks’ participation in intercollegiate athletics. In June 1940, Henley sent Wells a memo: “No written rule in the Big Ten regarding participation in athletics. The unwritten rule subscribed to by all schools precludes colored boys from participating in basketball, swimming, and wrestling.”

Basketball, swimming, and wrestling. All that skin, sweat and contact, so close to the fans. It would only take a small extension of the Gaines case to open up Indiana University to lawsuits and embarrassment.

By the summer of 1947 the pressure to speed up campus integration was bearing down on Wells. Faburn DeFrantz liked Wells, and the NAACP’s national office considered him “a decent fellow” on a reactionary campus, but DeFrantz and the NAACP were doing everything they could to keep up the pressure, including threats of more public confrontations. Future Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall, then the top litigator of the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, had met with black IU students in Indianapolis a year before and Walter White, national NAACP president, was preparing to visit Bloomington and discuss legal action if there was not visible progress in the coming year.

These threats had to be depressingly frustrating to Herman Wells. He hated the thought of expensive lawsuits and controversial publicity, and yet IU was at risk of both, over racial discrimination Wells would have preferred to end long before.

But he had so little room for maneuver. A public university, IU depended every year on a very conservative state legislature for its funding. The president of the IU Board of Trustees, Ora Wildermuth—effectively Wells’ boss—adamantly opposed integration. In refusing either to fund a dorm for black women or to integrate the existing dorms, Wildermuth had written to the Board’s treasurer at the end of 1945: “I am and shall always remain absolutely and utterly opposed to social intermingling of the colored race with the white … the further we go in encouraging social relationships between the races the nearer we approach intermarriage and just as soon as colored blood is introduced the product becomes black, and if the white race is silly enough to permit itself to intermarry with the black and thereby be swallowed up, it really, of course, does not deserve perpetuity. If a person has as much as 1/16th colored blood in him, even though the other 15/16th may be pure white, yet he is colored.”

A founding citizen of Gary and graduate of IU’s law school, Wildermuth had been elected to the IU Board in 1925 and remained a member until 1952, serving as president for 13 of those 27 years. For the university as he envisioned it, Wildermuth was a tireless supporter. He was an original incorporator of the IU Foundation, one of the most powerful engines for alumni support and fundraising among all state universities, and he was instrumental in raising funds for expansion of the IU libraries and construction of a fieldhouse (which today is the Ora Wildermuth Center for Health, Physical Education and Recreation). But he was dead-set against integration of the IU campus. “The average of the race as to intelligence, economic status and industry is so far below the white average that it seems to me futile to build up hope for a great future,” Wildermuth would write to Wells in 1948. “Their presence in the body politics [sic] definitely presents a problem.”

Caught between the pressure to integrate IU and the resistance around him, fearing lawsuits and bad publicity, Herman Wells had to step carefully. If he moved too slowly, he risked NAACP-backed lawsuits, which were starting to pop up on other campuses. But moving too fast—making just one impolitic step—risked setting off the tinderbox of reactionary administrators, cautious legislators and nervous alums, and maybe even provoking pro-integration lawsuits by publicizing the university’s Achilles heel. If Wells tried to integrate IU basketball with the wrong person and he failed—at his studies or in basketball or just buckling under the pressure—it would confirm the reactionaries’ every prejudice, make Wells look foolish and set the effort back for years.

And now, with the 1947-48 school year only days away, Faburn DeFrantz was at Wells’ door and the president knew the Chief expected answers.

DeFrantz and Wells saw each other as equals and knew each other well. Wells had spoken several times at the Senate Avenue Y’s Monster Meetings and had brought his mother (who lived with him in Bloomington and served as his official hostess) to dinner at DeFrantz’ home afterward. The two men shared similar abilities and aims, and they admired each other deeply. DeFrantz would write of Wells, “In him democracy found an ally.”

Wells’ office faced the thickest part of the campus woods; the shade of tall oaks and thick limestone walls protected it from the worst of the summer heat and made it a cool haven for DeFrantz and his companions. Wells greeted them with a warm smile and paused with each, asking how Spurlock came to Indiana from Illinois; when Kuykendall and Hall had graduated from IU; how long Ziegler had worked at the Y. “How’s Robert? Ready to start his sophomore year?” Wells asked DeFrantz, referring to DeFrantz’ youngest son, a student at IU.

“He’ll be even better if he can cheer for Bill Garrett on the basketball team.”

“Ahhhh … the basketball team,” Wells said, taking a seat.

“Herman, we appreciate all that’s happened at IU. You know we do. It’s made the school better and the state better,” DeFrantz began, to the nods of the other men. “But in this state, basketball’s what everybody looks to. Passing up Johnny Wilson didn’t do anybody any good. And he’s proved it with what he’s done. [In his freshman year at Anderson College, Wilson had been one of the highest-scoring college players in the country.] It’s embarrassing—to everybody. It’ll be the same thing, only worse, if Bill Garrett gets away. And he’s about to. I don’t know if you know this, but Garrett’s already gone to Tennessee State, and I’m not sure he’d come back even if he thought he could play here.”

No one moved, as DeFrantz continued: “He’s more than a great player. He can handle it. He’s grown up around white people in Shelbyville. Integrated high school, integrated team, good student, no chip on his shoulder. Hell, he’s already taken all the abuse a crowd can hand out, and he’s handled it.”

DeFrantz leaned forward, his eyes holding Wells’, one politician’s way of telling another that this mattered, that Wells’ response would be long remembered by DeFrantz, his companions and everyone they would meet in the coming years. “Herman, you know as well as I do that stupid gentlemen’s”—DeFrantz spat the word—”agreement can’t last. Any year now somehody’s gonna break it. And when they do it’s going to be really embarrassing—to all of us, Herman, and hard for all of us to explain—that the state that plays the best basketball had outstanding Negro players two years in a row, and that we asked you twice, Herman, and that somehow, some way, it just couldn’t get done.”

It was neither a negotiation nor a lament. Fabum DeFrantz had laid his best card on the table and the message was clear, reinforced by the presence of the witnesses and lawyers he had brought along: Take Bill Garrett or we will do everything we can to embarrass Herman Wells and Indiana University over segregation in basketball.

The president needed to buy time. He fell back on his often-used tactic of feigning ignorance and surprise: “Chief, I don’t know of any formal barrier to a Negro’s playing basketball here. I’m surprised to hear you say that. I can tell you without any hesitation that Bill Garrett can come here as a student if he has the grades. But I can’t order Branch McCracken to play somebody. Only the coach can decide who’s good enough.”

DeFrantz saw his opening. “So … Herman … if Bill Garrett comes to IU, and he’s good enough to play basketball on McCracken’s team, he can play here. Is that what you’re telling me?”

Wells’ chuckle lifted a bit of the tension. They all knew DeFrantz had won the first move, but they also knew many more moves had to play out. “I will speak to Branch McCracken about Bill Garrett,” Wells said. “That’s as much as I can promise you. I’d suggest you talk to McCracken, too.”

DeFrantz sat back, stretched his arms and loosened his tie. Dorothy Collins, Wells’ assistant, poured coffee all around. Wells asked about the Monster Meetings of the previous spring and plans for next year. He asked Al Spurlock if Crispus Attucks was still having trouble scheduling basketball games. On a cooler day Wells might have shown them around campus and pointed out plans for new dorms, new classroom buildings, expansion of the health center, maybe stopped by his home so those who had not already done so could meet his mother. But the outdoors was not inviting and their harder meeting was ahead of them. They finished their coffee and said their goodbyes.

The minute his office door was closed Wells asked Dorothy Collins to call McCracken at his office. The fieldhouse was not five minutes’ walk away, so he wasted no time. “Mac, DeFrantz brought with him two prominent lawyers from Indianapolis, a teacher from Crispus Attucks and his assistant at the Y. They’re courteous, of course, but he laid it straight out: Either Bill Garrett gets a chance to play basketball here, or they will go public and do everything they can to embarrass IU, along with you and me.”

McCracken started to reply, but Wells cut him off. “I told them of course Garrett could enroll at IU, that your job was to coach the basketball team and make decisions about which IU students are good enough players to play on your team.”

There was a pause. McCracken had never been comfortable calling the president by first name. “Mr. Wells, it doesn’t make any difference to me he’s colored, but there’s an understanding in the Big Ten. The other teams might cancel games. The conference might suspend us. Some of my own players might quit. I think we ought to step back and think about this.”

Time was getting short. DeFrantz’ group would be at McCracken’s door any minute. Whatever Wells wanted to tell McCracken about how to balance the risks and pressures weighing on both of them, about which direction he and McCracken would take Indiana University in the days and years ahead, he had to say now. Wells paused for just an instant, his mind perhaps going back a few months to the widely publicized story of how Ford Frick, the presdent of baseball’s National League, had backed Jackie Robinson and quelled a threatened players’ strike.

“Mac, I will take care of the Big Ten,” Wells said. “I’m the head of the Big Ten Presidents’ Group this coming year. I will deal with the other presidents and make sure there’s no suspension or canceling of games. I don’t think your players will quit, but I’ll back you no matter what the reaction is. All I ask is that if Garrett comes here you give him a chance, and if he’s good enough to play, you play him. I’ll take care of the rest.”

Wells heard a loud knock at McCracken’s door. “I’ve got to go, Mr. Wells,” the coach said. “They’re here.”

Butler Fieldhouse photo courtesy Indiana High School Athletic Association. DeFrantz photo courtesy Indiana Historical Society.

All other photos courtesy Indiana University Athletics.

This article originally appeared in the March 2006 issue.