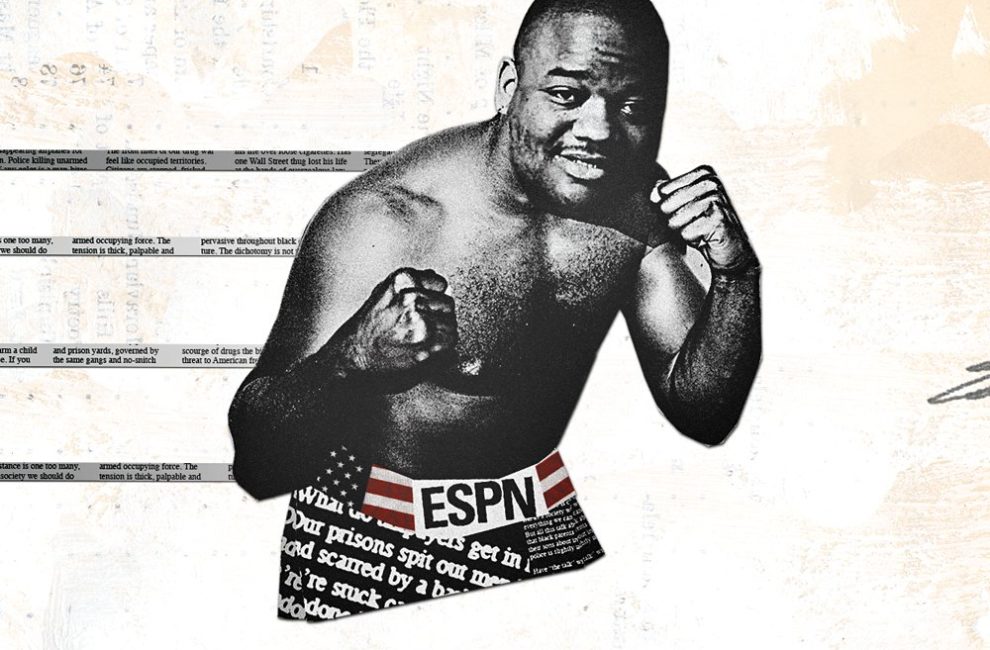

Jason Whitlock: No Pulled Punches

Gambling is in Jason Whitlock’s blood. His grandfather ran a “numbers” game on the south side of Indy decades ago. His dad hosted a makeshift casino at the Masterpiece Lounge, a bar he owned on Sherman Drive. His uncle ran a “pea-shake house”—an illegal lottery, basically—out of a local dry-cleaning business. Is it any surprise that Whitlock’s career as a sports journalist has amounted to a series of gambles?

In 1989, when Whitlock was a promising offensive lineman at Ball State University, he abruptly quit the football team to escape overbearing coaches and the “businesslike” nature of the college game. An unfocused student until then, he strode into the offices of The Ball State Daily News and asked to be put to work. “I had a long way to go,” he says. “I knew almost nothing.”

When The Kansas City Star hired Whitlock as a sports columnist in 1994, he quickly built a reputation for confronting issues of race in his columns. Historically, sports columnists—typically white males—avoided addressing the subject in a serious way. Whitlock’s approach earned him plenty of critics and fans alike, along with a $40,000 raise just six months into the gig.

In 2002, when ESPN hired Whitlock to write for its Page 2 website alongside Hunter S. Thompson, Bill Simmons, and other big names, Whitlock wasted no time in complaining about his compensation and quitting the column. In his reduced role as an occasional television personality, he blasted two of his ESPN colleagues in an interview, essentially daring the network to fire him. It did.

So naturally, it came as a shock to observers when ESPN took its own gamble and rehired Whitlock in 2013 to run a new satellite website, The Undefeated. According to the sports network, the site, which launches this month, “will be the premier platform for intelligent analysis and celebration of black culture and the African-American struggle for equality.” Considering the recent national conversation around race, The Undefeated seems primed to earn attention and controversy right out of the gate. That’s at least partly why ESPN president John Skipper chose Whitlock for the job—even if the odds of stability with Whitlock are always long. “Maybe I was impulsive in my choice of Jason,” Skipper says. “But you have to go with talent.”

Whitlock grew up on Grant Street, near 38th and Sherman, an area that even in the early 1970s was considered “the hood.” His parents, James and Joyce Whitlock, divorced when he was 4. He and his older brother, James Jr., stayed with their mom, visiting their dad every other weekend. One night, while the Whitlock boys were at their dad’s house, Joyce awoke to an intruder entering through her window. In short order, she found a second job and moved her boys to Nottingham Village, an apartment complex in relatively safer—and whiter—Warren Township.

The Whitlock boys remained connected to their old neighborhood through their father, who worked at Chrysler and as a barber before establishing himself as a bar owner. James Whitlock Sr. shared a number of things in common with his younger son—his love of talk, sports, women, and gambling among them—but they parted ways on the issue of race. “My dad was far more skeptical of America and white people than I am,” Whitlock says.

James Sr. wouldn’t have been comfortable living in Nottingham Village. When Joyce and her boys moved in, they were one of only two black families in the entire complex. Joyce didn’t mind, though; as a factory worker and union rep at Western Electric, she had plenty of white friends. And soon her sons, who were now attending the mostly white schools of Warren Township, did too.

Jason, a talented football player with the gift of gab, was particularly popular. So much so that when a federal desegregation order forced Indianapolis Public Schools to bus inner-city black students to Warren Township schools in 1981, school officials tapped Whitlock to act as an ambassador to the new kids. He was even interviewed by The Indianapolis Star about what the incoming students could expect at Stonybrook Middle School. His take? He was treated well there. Why should it be any different for the new kids? The reality was a rude awakening. “It was different for them,” he says.

Whitlock was in a tough spot. He had become fast friends with the arriving students who looked like him and liked the same music he liked, but not all of his white friends followed his lead. Over the years at Warren Central High School, Whitlock witnessed discrimination against many of his black friends. He remembers the basketball coach cutting two of them in favor of a couple of mediocre white players. Yet it seemed Whitlock was immune to similar treatment. Why? “I was an all-state football player,” Whitlock says. “I brought value to the high school. Talent is the equalizer in America. Had my friends been more-talented basketball players, maybe the basketball coach would have made a different decision.”

Big and strong-willed, Jason Whitlock was born with football talent. But journalism didn’t come so naturally. He had to work hard at it—first in college at Ball State, and then at a series of low-profile jobs. His first stop after graduating was at the Bloomington Herald-Times, where he covered high-school sports part-time for five bucks an hour. It was grunt work, but it gave him the opportunity to work alongside celebrated sportswriter (and Bob Knight’s buddy) Bob Hammel, who became one of Whitlock’s earliest mentors.

A year later, The Charlotte Observer gave Whitlock his first full-time reporting job. Officially, he was on the high-school sports beat. But he also reviewed rap albums and movies. His brother, James, recalls reading a review Jason wrote of Malcolm X and recognizing something special in it. “He was very insightful for someone his age,” he says.

Whitlock moved on to The Ann Arbor News in 1992, where he was charged with covering University of Michigan athletics. At the time, Michigan’s “Fab Five” basketball team was the biggest story in college sports. That helped Whitlock find a wider audience, and he soon landed his first gig as a sports columnist at The Kansas City Star in 1994. It didn’t take him long to become that city’s most loved (and loathed) sports commentator. The Kansas Jayhawks basketball team and the Kansas City Chiefs both frequently felt the sting of Whitlock’s poison pen. As Whitlock built his audience, he also developed his brand around a willingness to address the subject of race in a bold, unflinching way. He tackled topics others wouldn’t touch, such as when he wrote about how the popularity of the N-word among blacks reflected a society where “black people live in total fear of each other.”

Whitlock’s success at The Star earned him his first national platform at ESPN’s Page 2. When he shuttered that column over a salary dispute and insulted ESPN personalities Scoop Jackson and Mike Lupica, the network let him go. Whitlock’s attack on Jackson was especially virulent. He accused Jackson, who writes in urban-black dialect, of doing a bad impersonation of the Saturday Night Live character Nat X. “Scoop is a clown,” he said. “The publishing of his fake ghetto posturing is an insult to black intelligence, and it interferes with intelligent discussion of important racial issues.”

After moving on from ESPN, Whitlock made a hobby of criticizing his former employer. He took special interest in its role in the Bernie Fine scandal. Fine, a former assistant coach for Syracuse University’s men’s basketball team, was the subject of an extensive investigative report by ESPN in which two men accused Fine of child molestation. Fine lost his job over the report, but Whitlock saw it as a smear campaign with scant evidence, conducted to win readers at the expense of a man’s reputation. So he wrote about it—again and again.

“I am like Kevin Garnett,” Whitlock says. “If I am on your team, I am a great teammate.” And if you’re not on his team? “I am a horrible opponent. I turn into Bill Laimbeer.” You might say Whitlock has gone Laimbeer against his own team from time to time. He did it when he attacked his fellow ESPN personalities. He left his job at The Kansas City Star in 2010 in a cloud of bad vibes as well, clashing with editors and publicly airing his grievances afterward. And he has often been accused of throwing his own race under the bus.

In 2007, when radio host Don Imus caused a stir by calling the Rutgers female basketball team “nappy-headed hoes,” Whitlock made his own headlines by using the occasion not to condemn Imus, but to call out hip-hop for creating a world where young blacks are “perverted, corrupted, and overtaken by prison culture.” The column struck a chord, landing him in the TV studios of everyone from Tucker Carlson to Oprah Winfrey.

So Whitlock is no stranger to criticism. But last summer, he was subject to an uncommonly exhaustive attack on his character when Deadspin, a popular sports blog, published a withering 10,000-word profile of him. Written by Greg Howard, a 26-year-old black journalist who at one point had been in talks with Whitlock to work for The Undefeated, the story painted the Indianapolis native as vindictive, tone deaf, poorly informed, and bad for black America. It also cited numerous interviews with black writers who were wary of working for him because it meant “working for a man who made his bones disparaging people like them to an audience of approving racists.” Howard didn’t name his sources, because, he claimed, “Jason Whitlock is a powerful guy.”

Whitlock called the Deadspin story “a fabrication.” But he is quick to add, “I like being monitored.” It’s doubtful Whitlock enjoyed it, however, when Howard penned another scathing critique for Deadspin in April. This time, Howard used leaked internal emails to paint Whitlock as a bumbling, paranoid, mean-spirited leader. If the first Deadspin story was the opening salvo, the second one was the coup de grace.

When ESPN hired Whitlock back in August 2013 to work at one of its offices in Los Angeles, The Undefeated didn’t yet have a name. The sports conglomerate had experimented with several “affinity sites,” intended to serve a narrower audience by offering features, analysis, and commentary rather than straight news. Perhaps the most popular is Grantland, edited by Bill Simmons. Whitlock, trying to explain his own new site to Simmons during a podcast last year, referred to it as a “Black Grantland.” To Whitlock’s annoyance, the name gained traction online. “I have a lot of critics, people who want to exploit and take my words out of context,” he says. “We are not going to be ‘Black Grantland.’ We are going to examine race and culture through the lens of sports.”

So far, the affinity-website business has been a mixed bag for ESPN. Sure, Grantland is successful. But the other big affinity site, Nate Silver’s FiveThirtyEight, garnered a number of poor reviews after its launch last year, including one from Silver’s former New York Times colleague Paul Krugman. Given that Whitlock was hired two years ago and The Undefeated is only now going live, many have wondered if it’s struggling before it even gets out of the gate.

Whitlock acknowledges that his colorful history with ESPN is one reason it has taken extra time to get everyone there on board. But over the past year, he has made big strides in filling out The Undefeated’s editorial roster. So far, his notable catches include Ebony editor-in-chief Amy DuBois Barnett; Washington Post columnist Mike Wise; and Jesse Washington, who covered race-related issues for the Associated Press.

Earlier this year, ESPN teased some stories from The Undefeated on its homepage, including a long profile of Charles Barkley. In some ways, Barkley’s outsized personality and tough-love critiques of black culture are eerily Whitlockian. Then again, Whitlock’s views on black issues are more coherent and consistent than Barkley’s. Whitlock rails against the use of the N-word among fellow blacks. He preaches self-respect and self-empowerment. He believes in not making excuses. In bootstraps.

Whitlock also speaks out passionately against the systematic racism perpetuated by American policies. In 2008, he wrote a feature for Playboy detailing the disastrous effects of mass incarceration on black culture. In 2012, after the murder-suicide of NFL player Jovan Belcher, Whitlock wrote about the need for stricter gun laws, raising the hackles of the National Rifle Association.

“If you study all of my work, I would probably be considered a progressive,” Whitlock says. Although he adds that his “perspective on what we should do as African Americans sometimes disagrees with the stereotypical liberal perspective.”

Clearly, Whitlock isn’t exactly sweating his critics. And it’s no surprise that even his harshest ones aren’t betting against him. Deadspin’s Greg Howard expects The Undefeated to succeed. “It’s not about Jason,” he says. “It’s about the staff that he has assembled. He has good writers over there. I can’t wait to read them, and I can’t wait to compete with him.”

Knowing Jason Whitlock, the feeling is mutual.