Remember the Tigers: Crispus Attucks, 1955 State Basketball Champs

Editor’s Note: The following oral history appeared in the March 2005 issue of Indianapolis Monthly, on the 50th anniversary of Crispus Attucks’s first Indiana high-school basketball championship. It was noted in the 2005 edition of the Best American Sports Writing anthology.

Imagine the shame of Indianapolis basketball fans in 1955. Going into the season, Indiana’s most populous city and the annual host of its high-school basketball finals had, in the tournament’s 44-year history, never produced a champion. This in a state whose cities, towns, and neighborhoods forged their identities on basketball scoreboards, whose citizens walked on air when their teams won and felt the crush of ignominy when they lost. Back when basketball was religion, winning it all was heaven.

The rest of the state reveled in the capital city’s suffering, especially when, in 1954, tiny Milan High School, representing a town of little more than 1,000 people, managed to capture the crown. Though Indianapolis accounted for nearly a quarter of the state’s population, it was rural Indiana that owned the myth of Hoosier basketball’s soul: hoops on barns, cracker-box gyms and, above all, underdogs.

But Indianapolis had more than basketball failure to be ashamed of. When the Ku Klux Klan came to dominate local politics in the 1920s, it laid the groundwork for social policies that kept the city racially divided well into the 1950s. As the Great Migration brought African Americans from the South to Indianapolis in search of jobs, an entrenched system of de facto segregation and discrimination relegated the majority of the newcomers to a few crowded ghettos and slums, mostly on the near-west side. With a thriving business district along Indiana Avenue surrounded by neighborhoods outside of which blacks were rarely welcomed, Indianapolis’s African-American community was virtually a city within a city. And Crispus Attacks, founded in 1927 when the Indianapolis School Board decided that all black students should be educated separately, was its high school.

Yet if Indianapolis blacks were mostly excluded from the mainstream of Hoosier life, they participated fully in one Hoosier tradition: the passion for basketball. The Tigers of Crispus Attacks were the black community’s pride and joy. And when, on March 19, 1955, Attacks defeated Gary Roosevelt, another all-black school, to bring home the state championship, they became legend—the first team from Indianapolis, and the first all-black team in state history, to win it all. Indeed, though the players didn’t realize it at the time, it is now believed that Attacks was the first all-black team to win a state-championship tournament in any sport, anywhere in the country. At the Division I college level, the five black starters of Texas Western University wouldn’t achieve a similar feat for 11 more years.

In the days after the tournament, it was clear that Attucks’s achievement meant different things to different people. “Hail to the Champion,” proclaimed The Indianapolis News. “Indianapolis joins with Crispus Attucks in the state championship celebration that has been so long awaited.” Indianapolis Star sports columnist Jep Cadou Jr. boasted, “They said no Indianapolis team ever could win this championship. The Tigers listened and smiled.” The City Council issued a resolution, and country clubs hosted steak dinners for the team.

Meanwhile, The Indianapolis Recorder, the city’s African-American paper, reminded its readers that Attucks had scored an upset over Jim Crow: a “triumphant climax to the dramatic battle of Negro schools through the decades.” As the Recorder suggests, for Crispus Attucks victory had been a long time coming. Shut out of the Indiana High School Athletic Association until the mid-1940s, Attucks, in the early years of its program, had difficulty even finding schools to play. Most of its team members grew up in relative poverty, and its gym was too small to accommodate its fervent fans. It took a driven coach, the late Ray Crowe, and an unprecedented assemblage of basketball talent, led by all-time great Oscar Robertson, to push Attucks past the obstacles and into the winners’ circle. But once they arrived, they remained: In 1956, Attucks became the first team to go undefeated while winning the championship. In 1959, they won it again.

Along the way, they got respect from a city that had spurned them. And in the end, they wrote a new chapter in the book of Hoosier basketball lore—one in which underdogs could be kids from urban ghettos, could grow up shooting in alleys and parks, could be black and be a vital part of the glory of the game.

NOT EQUAL

Although state law opened all schools to African Americans in 1949, most black high-school students in Indianapolis remained at Attacks because they lived nearby; even black students living in other districts chose to enroll in Attacks because it was still regarded as the city’s “Negro” high school. And just a few blocks away, the dirt courts of the Lockefield Gardens federal housing project were incubating some of the best basketball talent Indiana has ever seen.

Al Spurlock (assistant coach, Attucks): When I started teaching in Indianapolis, I had to teach in black schools because I couldn’t go anywhere else. I didn’t become too friendly with white people, because if we had gone downtown and wanted to stop for a cup of coffee, there was the potential embarrassment that the place wouldn’t serve me.

Harold Stolkin (businessman and Attucks booster): Still, the atmosphere in Indianapolis in the ’50s wasn’t nearly as bad as it was during the years of Klan dominance in the ’20s. My dad used to take me over to the corner of Meridian and Vermont streets to watch the Klan parades. I remember being in awe of them marching down Meridian Street in hoods and gowns.

Stanford Patton (forward, Attucks): My situation, like the rest of them, wasn’t the best. Things were real bad for us—a lot of poverty, no hope. We knew we were segregated. We knew where we could and couldn’t live. We knew where we were wanted and weren’t wanted. We were living in a caste system.

Sam Milton (guard, Attucks): In the South, my parents had worked on farms, and during the winter when there was no crop, you still stayed on the boss man’s farm. So in the summer, even after you’d done the crop, you wouldn’t have no money because you still owed him for staying all winter. Indianapolis was a lot different. Here you could at least make your own living. But you still kind of knew where you couldn’t go. And you accepted that. We thought we was living good.

Oscar Robertson (forward, Attucks): When you were poor, black, and from Indianapolis, there were three things you did: go to school, go to church, and play sports. You had no money for anything else. My father made a hoop I could roll out of the garage, and I’d go in the alley to shoot at it.

Bill Hampton (guard, Attucks): Nobody had anything. But everybody played basketball. If you didn’t have a rim, you’d cut the bottom out of a bushel basket. We’d play with a basketball until the air was out of it, then we’d stuff it with rags, sew it back up, and play with it some more.

Spurlock: A lot of the guys played in the Dust Bowl—courts made of dirt. In the dry season, when they played, a cloud of dust would rise up. You’d see shots that would amaze you. They held a tournament at the end of every year to find the Dust Bowl champion, and those teams could match up with any high-school team in the city.

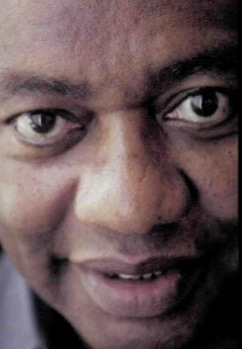

Robertson (pictured): A lot of us played together at the Dust Bowl. The competition was tough, because we couldn’t hardly go anywhere else around the city to play.

Hampton: Guys would come from all around, from Chicago and Evansville, to play there. Everybody would go on Saturday and play all day long. It didn’t matter who you were—when you lost, you might as well go home, because there were so many other guys waiting to play.

Sheddrick Mitchell (center, Attucks): I started shooting left- and right-handed hooks, and I got good at it. I lived in the Shortridge district, but when [star forward and ’53 Attucks grad] Willie Gardner saw me play, he said, “Don’t go to Shortridge—you need to go to Attucks.”

Willie Merriweather (forward, Attucks): I could have gone to Shortridge, too, because I lived within the boundary lines, but I eventually chose Attucks for the basketball program.

Bob Hammel (longtime Indiana sportswriter): They were trying to build something special at Attucks. The irony, of course, is that the school was created out of hate. The Klan conspired to dump all the blacks at one school to get them out of the rest of the schools. But from that background emerged something very special.

Maxine Coleman (cheerleader, Attucks): Our principal, Dr. Lane, always stood in the doorway to the school and tried to instill punctuality by yelling, “Two minutes! Two minutes!” You might get there 15 minutes early, and he’d still shout, “Two minutes!” When the boys would go out to participate in a sport, he’d say, “Bring home the bacon.”

Robertson: I think because it was a segregated school, it brought us together and made us stronger. We had the greatest teachers in the world. A lot of them had doctorates but couldn’t teach in the white schools. They were like parents, and the other students were like family. I was a shy kid, and Attucks allowed me to grow, both on the court and in the classroom.

Coleman: We had pictures of previous graduating classes in the halls, and it was like a second home—you could see your family members on the wall. It was quite an accomplishment just to be a member of the Crispus Attucks ball club, because of what they had to endure.

GREAT EXPECTATIONS

For nearly two decades after Attucks’s founding in 1927, the Indiana High School Athletic Association, which sanctioned the state basketball tournament, denied the school membership; the IHSAA’s skewed logic was that, because Attucks served black students, it wasn’t technically public. (Ironically, a “mental attitude” award would later be named for IHSAA director Arthur Trester, on whose watch Attucks was excluded.) Undaunted, the Tigers scheduled games wherever possible—mostly against Catholic and tiny rural schools. By the 1943 season, Attacks had played enough IHSAA teams that the organization finally let the school in. The Tigers quietly grew into a basketball force, going deep into the 1951 tournament behind the coaching of newly hired Ray Crowe and the play of stars Willie Gardner and future Indiana Mr. Basketball Hallie Bryant.

Stolkin: Ray Crowe was a customer at my auto-loan company, where a big part of our business was from the black community. I took an interest in Attucks partly through him and partly because it was the era of the advent of the black high-school athlete, when black kids were starting to get the recognition they deserved. I got on board in 1951, when they went to the Final Four of the state tournament. They were a favorite because of their talent. But Crowe drilled into them that it was their opportunity to be in the big time, and he wanted the school to be well-represented. He said, “Don’t commit any unnecessary fouls. Play gentlemanly.” As a result, they got beat by Evansville Reitz, an inferior team.

Spurlock: All the players on Ray’s teams were gentlemen. Some of them came from very bad situations, but Ray helped them—by going to their homes after school, seeing that they came to practice and games on time, checking with their teachers. And we never had any trouble with towel-snapping or horseplay in the locker room.

Merriweather: The whole team was in Mr. Crowe’s homeroom. He monitored our homework and told us we’d better not get into trouble. There was no such thing as getting a failing grade and thinking you were going to play. So you did your work.

Hampton: Coach Crowe would randomly call you at home, and he wanted to hear your voice. There were so many other guys waiting to be on the team, you did what you were supposed to do.

Merriweather: In ’53 and ’54, we were undefeated at the middle of the season. Then I went down with torn cartilage in my knee, and the team went on to lose in the state semifinals to Milan. When I talk to Bobby Plump [Milan’s star player], he tells me if I had played in ’54, his life probably would have been different. Because they wouldn’t have beaten us.

Spurlock: The next year, ’54-’55, we had practically the same team back, so our expectations were quite high.

Hammel: The faster game had already evolved by then, and they reflected that and mastered it. Oscar was so efficient, without having to slow down. It didn’t take a coach or a connoisseur to see there was something really unusual out there.

Hampton: Everybody could shoot the ball. We could just flat-out shoot. And the way we played was fun to watch, because all the parts worked properly.

Jim Cummings (reporter for the Recorder): They were a fast-break team with good rebounders and scorers and good guard play. And they had Oscar. A lot of the buzz around the city, and in the black community in particular, was that they would win the state title in ’55.

A SEASON TO REMEMBER

When the local school board built Crispus Attucks, they included a gym that seated only a few hundred spectators. As support for the basketball program grew, the athletic department was forced to schedule home games at other venues to accommodate fans. Playing in gyms around the city and across the state—but never their own—the Tigers rolled to 16 straight wins to start the ’55 season.

Spurlock: Crispus Attucks was built about the same time as Shortridge and Washington, but it didn’t compare. And after we started winning, we drew so many people we started renting Butler [now Hinkle] Fieldhouse. We’d play small schools there, and they’d bring what seemed like their entire town to watch.

Cummings: Attucks was also a draw in small towns because people wanted to see their own team score an upset.

Spurlock: Traveling around Indiana was a novel experience for most of the players. [Attucks athletic director] Alonzo Watford would call ahead to make arrangements with restaurants along the way so the team could eat after games. Some places refused to serve blacks.

Merriweather: Many times we’d pull up to a restaurant and Mr. Watford would run in, then run back out with big crates of boxed lunches. We just thought we were eating on the bus, having fun. We never knew we couldn’t eat there. He didn’t want us exposed to that prejudice.

John Gipson (forward, Attucks): Sometimes somebody would let us go in a back room where we’d be served. We couldn’t sit in front, or there’d be people all around trying to peek in the windows to see us. I guess we’d endured it for so long we’d gotten used to it. But it did make you think when you went to a service station to use the restroom, and they’d tell you you couldn’t. Still, we couldn’t afford to make a spectacle, because that’s what they wanted us to do. Then they’d be down on us.

Milton: A lot of us grew up in the South, so we was kind of used to the idea of just staying in your own place.

Robertson: We went to a lot of communities where they’d probably never seen black people. They were generally nice, just curious about who we were. We showed them we didn’t have tails—that was a myth for a long time, that black people grew tails at 12 o’clock. I think most people just had misconceptions. And they wanted to see these black stars run up and down the floor.

Hampton: A lot of people weren’t familiar with black athletes. They’d talk about how you could run, how you could jump.

Merriweather: We’d get into layup lines during warm-ups, dunking the ball, first right-handed, then left-handed, then with both hands. We’d put on a show. We’d look around and the other team would be out there watching us. Once in a while, somebody in the stands would say “Darkie” or “Black Boy.” And I’d hear them using the n-word when I took the ball out of bounds, and they’d say, “Don’t step on my feet” or “Watch yourself.”

Coleman: Usually, the other teams’ cheerleaders would come over to our side and give a cheer, and vice versa. And then at one point, we would kind of merge together and do a cheer. It was a matter of courtesy. But it usually seemed like it was us against them.

Stolkin: My son and I used to travel with the team and sit on the bench at games. There were people who were openly hostile, like they were looking for a fight. There was still just an awful lot of prejudice toward a black team. By looks, innuendo, or remarks, it was obvious they also resented me. They’d look at me—a white guy—as if to say, “What are you doing supporting this team?” But eventually, people were forced to accept them.

Cummings: Attucks just started winning and winning. I think they felt momentum toward destiny that year.

Merriweather: We were ranked second in the state behind Muncie Central and beating everybody in sight. I think we felt we could beat anybody.

Patton: After one game, where we beat the other team pretty bad, I saw a player from the other side crying. I was standing there, and the boy’s daddy walked up to him and said, “You might as well stop that crying. Because can’t nobody beat them. You ought to be glad you ever played against them.”

Spurlock: When we played in Connersville the gym was so crowded, it heated up in there. We found out later that the gym was built over a swimming pool.

Merriweather: At halftime, they opened the gym doors to cool the place off, and condensation settled on the floor.

Gipson (pictured): We were sliding, and the refs were calling traveling. Of course, Connersville had to play under the same conditions, but they were used to it.

Merriweather: We were one point behind near the end of the game, and a Connersville player was coming down the sideline. People in the stands were almost on the floor—it was that close. I made it to the out-of-bounds line, thinking he’d either have to charge over me or stop. Instead, he ran up on the seat of a spectator, out of bounds, then went in for a layup. The referee never called it. I was standing there dumbfounded. We lost the game.

Spurlock: We knew about homer calls. The boys were taught to ignore them—just go ahead and try to score points. Our players would raise their hands and then go about their business of trying to beat the other school. That was Ray’s main rule—don’t question the referees.

Merriweather: Most of the teams we played were predominantly white. And the referees all were white. We knew through experience to expect a certain amount of favoritism. They talk about home teams getting “home-cooking,” and that was always the case on another team’s home court. Coach Crowe told us, “Think of us as being 10 points behind from the beginning.”

Milton: The home team could push you and do this and that, but you had to tap dance or you’d get a foul.

Merriweather: We were told that we had to be in better shape, better focused, and better rested. But going into the finals of the city tournament, against Shortridge, Coach fed us and let us sit around, talking to one another, relaxing, not being monitored. It was almost a disaster. We ate, then he left, so we ordered again. We had chicken and all kinds of food, and when the game started, we were all zonked out from overeating. We were just one step slower.

Gipson: We were still tied after the first overtime in that Shortridge game, so we went into sudden death. First person to score, free throw or basket, would win. When Oscar got the ball, he waved everybody aside. He took over offensively all the time, but just to wave everybody off—that was the first time we’d seen that. He was going to go around his man, so he kind of stutter-stepped, but he saw that the defender was going to give him room, so he just raised up and hit the jumper.

Merriweather: We beat Shortridge in double-overtime. But later, when we went to the tournament, guess what we ate before games? Bouillon soup and toast.

MARCH MAYHEM

In 1954, after advancing past Attucks in the state semifinals, Milan had gone on to beat Muncie Central in the title game. A perennial powerhouse, Muncie Central returned for the ’55 season with another strong lineup and, going into the tournament, reigned as the top-ranked team in the state. Attucks, which had finished the regular season with one loss, breezed through the early rounds of the tourney, but the Bearcats, an integrated team with two black starters, cast a large shadow over the Tigers’ championship aspirations. The two teams would meet in the semifinals—a match-up heralded as the “Dream Game.” It would go down in Hoosier legend as one of the great contests of all time.

Gene Flowers (forward, Muncie Central): Attucks had a fine ball club, and so did we, so we figured we would run into them in the tournament. Initially, we thought we’d meet in the finals, because the year before we had gone through the Fort Wayne semi-state group. But at the last minute the IHSAA switched us to the Indianapolis bracket. I think they wanted more people to fill up Butler Fieldhouse.

Robertson: For us, that game against Muncie Central was like the final game. They had great athletes, and so did we. I’ll never forget the game as long as I live. It was nip and tuck, nip and tuck.

Flowers: I was guarding Oscar, and he was guarding me. I sat out some of the game with four fouls, and they got ahead of us. Then we came back and got ahead of them, back and forth.

Merriweather: I fouled out when we had a six-point lead with a minute to go. By the time I reached the bench and turned around, we were down to a one-point lead. I thought, “Oh my goodness, what are they doing out there?”

Flowers: We got the ball and were coming down the court, hoping to score. [Muncie Central guard] Jimmy Barnes was driving with the ball, and I was open on the wing. All I had to do was catch a pass and lay it in.

Gipson: But Oscar was one of a kind—he saw the whole floor. And he saw Flowers under the basket. After they threw it in, Oscar just ran down the court, jumped up, and got the pass.

Hammel: That was the first tournament I covered, with the Huntington Herald Press. In a way, Oscar ruined it for me, because after seeing him, no other player could ever even come close.

THE BIG GAME

When the final four teams of the ’55 tournament were set, it looked as though history was in the making. No team from Indianapolis had ever won a title, and Attucks was favored to break through for the first time. Of the state’s three all-black schools, two—Attucks and Gary Roosevelt—were in the finals facing integrated teams. A headline in the Recorder proclaimed, “13 Negroes, 7 Whites Are Big Four Starters” and concluded “the sepia player has come into his own as never before.” After Attucks handled New Albany, and Roosevelt eased past Fort Wayne Northside, it was decided: The champion team would be from a black school.

Merriweather: Each game, the frenzy was getting higher. As we started moving toward the finals, it was hyped by the media. They’d have pep rallies in the auditorium at school, and the principal told the students that how they carried themselves reflected on the team. It seemed like everybody in the community bought into it. When we won, everybody won.

Hampton: We knew we had an opportunity to do something no other team in the city had done.

Robertson: It got to the point where instead of being Crispus Attucks, we were called Indianapolis Crispus Attucks. Of course, we thought we had been Indianapolis Crispus Attucks all along.

Gipson: Some whites had a little resentment toward us, but once we got to where we was winning, they saw how decent we were. We didn’t degrade anybody on the court and didn’t trash talk. If someone got knocked down, we’d help them back up. People started getting on the bandwagon.

Hampton: When we got to the finals, everything was Crispus Attucks. Everyplace you went it was green and gold. When we played Gary Roosevelt, the Fieldhouse was alive and warm.

Patton: I don’t think it had ever happened before, that the whole city got behind one team. That showed me something. I knew they didn’t really have to like us, but they had to respect us for what we did and how we did it.

Stolkin: When Attucks got into the finals, I noticed that white cheerleaders from the other high schools in Indianapolis had representatives on the sidelines. They were supporting Attucks. That’s the first time I saw that.

Dick Barnett (forward, Gary Roosevelt): At that age, we had no historical perspective on what it meant for two black teams to play each other in that setting at that time. We were just having fun, proud of getting our school into the final game.

Spurlock: It made it easier for our players that Gary Roosevelt was our opponent. Since there were two black schools, there had to be a black champion.

Milton: In the locker room before the game, Crowe said, “We know it’s going to be fair, because both teams are black.” There wasn’t going to be any hanky panky with the calls.

Merriweather: But we thought we’d have a tough time against Roosevelt, because they’d been pasting teams, too. When they hit that first shot, I thought, “This is going to be a hard game.” The next thing I knew, we had a 12-point lead, just like that. Then it was 20.

Barnett: We were down at halftime, and as the game progressed, with Oscar running things from the top of the key, it was obvious he was going to be tough to beat.

Merriweather: Barnett wound up with 18 points, I think, but I kept him in check into the fourth quarter. At one point, he intercepted a pass and I met him at the basket, blocked his shot, and fouled him. When I went to help him up, he said, “Get your hands off me, motherfucker.” I said, “Well, screw you then.” After that, it was on. I didn’t let him breathe.

Hammel: My only surviving memory of that championship is what a blur it was. It was darned near impossible to keep score. The year before, in the Milan–Muncie Central game, the final score had been 32-30. In this one, Attucks had 51 points at halftime. I don’t think even those of us covering it appreciated what elevated talent we were watching.

Merriweather: We won 97-74.

WINNERS’ CIRCLE

For many observers, Attucks’s triumph symbolized the achievement of aspirations long suppressed. And by bringing Indianapolis its first state title, the players had, by virtue of their extraordinary talent and impeccable conduct, endeared themselves to much of the city. After the game, according to the Recorder, “About 12,000 persons lined the Monument [on Monument Circle, the centerpiece of downtown Indianapolis] and wildly cheered as Mayor Clark presented the key to the city to coach Ray Crowe and the coach in turn introduced his players.” However, not everyone remembers it that way.

Gipson: When the game was over, we went down to the locker room, and Crowe told us to watch our conduct because we were going to be under a microscope—don’t get into trouble, don’t put a blemish on what we did.

Spurlock: We went out and got on a fire truck that carried us down Meridian Street, to downtown and around the Circle. People along the way stood outside and cheered and waved at us.

Merriweather: After we rode around the Circle, we went out Market Street and then up Indiana Avenue to Northwestern [now Watkins] Park to a bonfire. That’s where we got off, at the bonfire. We danced and hollered and sang songs.

Hampton: Northwestern Park was in the heart of the black community, and it was like going from Indiana to Florida—we left the frigid atmosphere of downtown to go back where it was warm and we were accepted. People were grabbing us, and at one point I had to say, “Look out, lady—you’ll tear my jacket.”

Merriweather: Apparently, other teams that had won the championship had gone to the Circle and stopped and sat around on things and had their pictures taken. I don’t remember stopping. We stayed on the fire truck, just waving at people. If Coach Crowe stopped, he must have been on another fire truck. It wasn’t the one I was on.

Robertson: I don’t remember stopping at the Circle, either. When they sent us back out to Northwestern Park, I thought that’s what they did all the time. We were just naive. We didn’t know that it wasn’t supposed to be that way.

Gipson: We heard later that city officials had come to the school prior to us winning the tournament, saying that if we did win, they thought our people was going to tear up the Circle, tear up downtown. That’s why they rerouted us.

Hampton: But our fans hadn’t done that the whole time Attucks was winning, so it wasn’t called for. It just left a scar on the entire event. It meant they thought we should go back out where we belonged.

Robertson: Maybe the fathers of Indianapolis said, “We don’t want these black kids in downtown Indianapolis.” And Ray Crowe’s gone now, but I would like to think he wouldn’t have stopped just to get a key from a mayor who was then going to kick him in the butt and say, “Now get on out of here.” I don’t think he did that.

Stolkin: The kids were aware of an undercurrent of resentment that a black team had done what they did. But I’m not saying all whites were against Attucks. I think the majority of white people around here really admired them.

Spurlock: I think the city as a whole was quite proud of the team. That championship, like no other occasion in Indianapolis, helped bring about a better feeling between whites and blacks. Barriers started coming down. The community did everything it could to show appreciation. And the players felt that what they had done meant something.

Gipson: The black community was behind us all the way. I used to get off work from the bowling alley, and older guys from the neighborhood would say, “What are you doing out, boy?” I thought they was ready to jump on me or something. But they’d say, “Where you live at?”—then take me home. I guess our success was the only thing they had.

Merriweather: Everywhere you went, people recognized you and gave you a hug or a handshake. “You guys really did it,” they’d say. The honoring went on and on. A lot of people wanted to do stuff for you—“Why don’t you come on over to the restaurant? You can eat for free.” I went to my barber and he said, “You don’t have to pay. Come get a couple haircuts on us.”

Milton: People gave us jobs so we could make a little money over the summer. It was easy to get dates, and people always wanted us to come to parties.

Coleman: We were proud of the team because they were winners. We felt extra special because all bets were against them, and, except in the black community, everybody was rooting for everybody else. And you know every athlete is popular with the girls. You know that.

Gipson: The Walker Theatre on Indiana Avenue—we never paid to go in there. If people saw you on the street thumbing a ride, five cars might stop. We were celebrities. On top of the world. You couldn’t walk down the street without somebody stopping you. I walked to my uncle’s house the day after the championship, which wasn’t but five blocks away, and it took me an hour to get there.

Merriweather: When Joe Louis would win, and everybody in black neighborhoods ran into the streets screaming and hollering, blowing horns and all that—it was almost the same way with Attucks.

John Clemons (guard, Attucks): When we walked down the street, everybody would say, “There go the champs. There go the champs.”

LIVING LEGACY

Fifty years after the history-making win, the surviving Tigers and their supporters agree that the team changed life in Indiana—and perhaps beyond.

Spurlock: Indianapolis schools began to integrate after the state law was passed in ’49, but they didn’t start real integration until a few years later. Basketball was one of the things that drove it. When people found out that African-American students could play basketball and could be coached, people at white schools wanted to get some black athletes on their teams to help them out.

Hampton: People were afraid we had built a dynasty. When the Klan created this daggone thing, they were thinking, “We’ll just let them stay where they belong.” But then with us finally being in the IHSAA, they realized what the outcome was going to be for years to come. “We created this monster,” they thought. “Now we’ve got to figure out a way to break it up.”

Robertson: After that, even if you were black, you had to go to the school in your district. You could not leave your school district to go to Crispus Attucks.

Hammel: I’m not unusual in that now, at a game, I don’t see black and white. A lot of that started with the Attucks team, and particularly with that first championship game—the way Attucks emerged in this predominantly white state, in a predominantly white sport, and took it over. But I don’t think there was any feeling that they had made it unsuitable for whites. Their color quickly became irrelevant. As a state, we needed that badly.

Spurlock: Basketball was such a religion, it was a good way to bring the races together. People saw that when blacks achieved something, they didn’t go wild, that they represented something the entire community could be proud of.

Gipson: People saw the kind of guys we were. We were decent people. We weren’t criminals or hoodlums. I guess the masses, the whites, figured, “Hey, these guys on the team aren’t that bad; maybe those other people aren’t either.”

Patton: We destroyed a lot of myths—that a black man couldn’t out-coach a white man, that we would break under pressure, that we was cowards. That was the perception people were introduced to, that even we blacks had believed.

Gipson: Before, when we went to shows in other neighborhoods, they’d make us go to the balcony. You couldn’t sit downstairs. But once we started winning, we could sit anywhere we wanted to. It’s sad to say, but because we were on the basketball team, we broke down some doors.

Stolkin: People began to realize that blacks were entitled to their place in society. It was a tremendous stride, because in the ’20s, when the Klan was so strong, it just wouldn’t have been possible for a black team to do that.

Patton: To this day, when I tell people I played in the state where the Ku Klux Klan had its headquarters, they say, “Dang, how’d you make it?”

Hammel: There was the thought that if blacks could do it in Indiana, they could do it anywhere. And they could bring people with them. More than anybody else on the court, that’s what Oscar did. He was so singularly good, who cared what color he was? People said, “He’s a Hoosier. That’s somebody to be proud of.” Oscar carried a banner that was socially significant.

Spurlock: It started to get spread around the nation that a black school in Indianapolis had won the championship. Articles appeared in African-American papers throughout the country. Later, when Oscar achieved notoriety as a professional, he would spread the word around wherever he played.

Mitchell: What Attucks did has never really been publicized. Of course, they did a movie about Milan [Hoosiers, released in 1986]. Milan came from a small town and won the state. But now ask yourself: Is the magnitude of what Milan did greater than Attucks?

Patton: We wrote our own history. Nobody was writing it for us. We were the pen behind it. No one could explain us out.

Hampton: When they talk history, they don’t talk about what could have been. They talk about what was. They don’t talk about third best or second best. They talk about the best. And when they do, they talk about Crispus Attucks.

Robertson: We gave the black community hope. They heard talk about how blacks were lazy, how they don’t want to get up and go to work, how they have too many kids. But when Attucks started to win, they could brag on us. There were people in the city who got up in the morning and felt good about themselves when they looked in the mirror. All because of what Crispus Attucks had done.

Gipson: The summer after we won the first championship, white guys from other teams would go around playing ball with us.

Mitchell: We even tried to get white guys to come to Attucks. We almost had one—he was good enough to play on the team but changed his mind at the last minute. That would have been something. They would’ve made a movie about that.

Photos by Tony Valainis and AP Photo/Ric Francis; archival images courtesy Indiana High School Athletic Association, Indianapolis Recorder Collection, Indiana Historical Society, Indiana Basketball Hall of Fame, and John Gipson