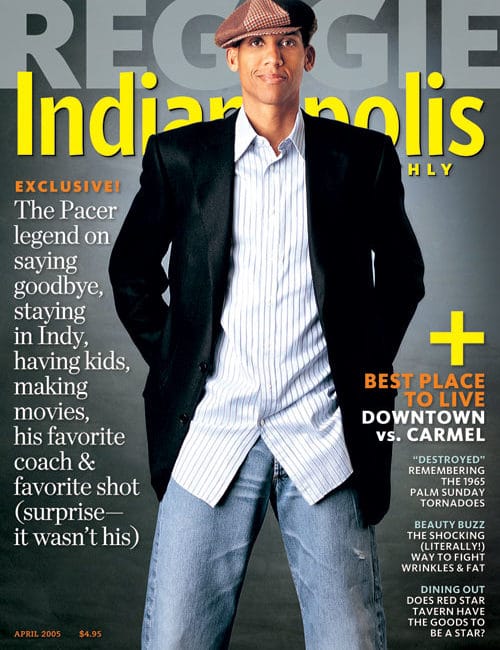

The Hoosierization of Reggie Miller

Editor’s Note: Indiana Pacers hero Reggie Miller was inducted into the Basketball Hall of Fame on April 2. Here, his cover story from IM‘s April 2005 issue. (See the companion Q&A piece here.)

He got to start a game in high school only after another boy showed up with the wrong uniform. He got a basketball scholarship at UCLA only after three other recruits turned down offers. He was born with hips and legs so contorted that doctors suggested he might never walk, and he wore leg braces until he was 4. When he first turned on to basketball, he couldn’t even beat his sister at backyard H-O-R-S-E. He was always thin, even in ninth grade at 5’9″ and 140 pounds, and when he added 10 inches but gained just 50 pounds, he was downright skinny. He compensated for his count-my-ribs physique with on-court garbage talk, a spit at an opponent, a choke sign at a referee; in college, a rival band taunted back, waving big paper ears on the sides of their heads when he stepped onto the court. He reveled in being the crowd-spoiler, a real bad boy. He wore sunglasses indoors. He wanted people to call him “Hollywood.”

And it was on this Left Coaster from L.A.—L.A.!—that Pacers General Manager Donnie Walsh spent the 11th pick of the 1987 NBA draft, shunning homegrown Hoosier hero Steve Alford in the process. Alford, the former Mr. Basketball who’d led Indiana University to an NCAA title and played on the U.S. Olympic team, stood on his parents’ New Castle lawn that day and said he couldn’t guess what the Pacers were thinking in drafting Reggie Miller. “Where he fits in with the Pacers,” Alford told reporters, “I don’t know.”

The Pacer faithful didn’t know either. At a Market Square Arena draft party, fans booed. They didn’t know it at the time, but they were, in their stubbornness, giving Miller his favorite nourishment: a challenge, an enemy, a reason to fight. Eighteen years later, if there’s one thing Hoosiers have learned about the out-of-state guard who made it known that Indiana’s basketball tradition doesn’t stop at high school and college, it’s that he loves to be hated. Consider the advice Miller’s older sister/best friend, women’s basketball phenom Cheryl Miller, once gave New York Knicks fans: “The bigger the hatred, the more Reggie thrives. If New York wants to do themselves any good, shut up.”

The day after the draft, Walsh sat beside Miller at an Indianapolis press conference and told reporters, “I think our time is going to come.” Given the Pacers’ brief and lackluster history in the NBA, he sounded more hopeful than prophetic, but the 21-year-old who would bring that time to Indiana nodded at every word. Miller didn’t tell the Indianapolis media his private hope that their city would be nothing like South Bend, the only piece of Indiana he’d ever seen. Instead, when reporters asked him about transitioning not just from college to pros, but from West Coast to Midwest, he summoned up the closest thing to a compliment he could think of: At least Indianapolis, he acknowledged, wouldn’t have as many off-court distractions as L.A.

And so it began for Reggie Miller and Indianapolis, Indianapolis and Reggie Miller. The time was ripe for the two to find each other. The Pacers, once the dominant team in the old American Basketball Association, had lost their way. The old squad was packed with legends: ABA Pacers George McGinnis, a three-time ABA All-Star; Mel Daniels, a two-time ABA MVP; Roger Brown, the first player signed by the Pacers; and Bob “Slick” Leonard, the winningest coach in ABA history. When the ABA folded in 1976, the Pacers were one of only four teams that paid the multimillion-dollar NBA entry fee. To survive long enough for a second NBA season, they had to sell season tickets in a local telethon. When Miller arrived in time for the team’s 12th season in the league, the Pacers had made the NBA playoffs only twice and hadn’t had an All-Star since 1977.

The summer he was drafted, the Pan-American Games were coming to Indy, and the U.S. team was playing exhibition games against pro players to prepare. Though he had no signed contract and no guarantee that he wouldn’t get hurt before his NBA career even began, Miller wanted to play. His father tried to talk him out of it. His agent said no. But Miller hoped to introduce his game to the Hoosier doubters, show them what he could do. At the Pan-Am exhibition game in Indianapolis, before he ever wore blue and gold, he was booed.

He spent most of his first season as an understudy, the third guard on the squad. Playing backup to veteran guard John Long, the Pacers’ second-best scorer the previous season, he started just one game, when Long got hurt. And to everyone’s surprise, it turned out that the brash kid relished the part of humble rookie, player-in-training; he said he appreciated the chance to learn the NBA without having to produce standout stats. “Reggie just wanted to fit in,” says Hoosier hoops legend Larry Bird, then a Miller opponent on the Boston Celtics, now Pacers president of basketball operations. “He wanted to see how this league worked.” So “Hollywood” got put on hold. Gone was the ref-baiting, the hotdogging, the trash-talking that had garnered so much attention in his UCLA days. “The things I did in college?” he said that first season to a reporter from the Los Angeles Times, his hometown paper. “What goes on here makes me look like a sissy.”

He learned to let his game do the talking, to warm Pacer fans to his brand of ball. That wasn’t too hard, considering Hoosiers thought from-the-outside, pure-shooting, disappointed-if-it-hits-the-rim-on-the-way-in basketball was a lost art outside of Indiana. Forget that Miller didn’t hone his shot off a barn backboard; he learned to shoot from the outside because his sister blocked his runs at the goal. “He’s never afraid of taking a big shot. People who understand the game and appreciate the game, like people in Indiana, understand what he has to offer,” says Larry Brown, the Detroit Pistons coach who led Miller and the Pacers for four years. Off the court, Miller, intentionally or not, was also honing his down-home image. He lived for a while in downtown Indianapolis, and told national media he liked it. (Do you remember how barren downtown was in 1989?) A Sports Illustrated writer who visited Miller in those early years reported that he served drinks to guests in plastic giveaway cups from White Castle.

And then a funny thing happened on Miller’s path toward Hoosierization: The Pacers started winning. Playoff appearances became as commonplace as Miller three-pointers. In 1994, the team came back from a 17-point deficit to top Orlando in the first game of a first-round Eastern Conference Playoffs series. The heavily favored Magic never got their game back, and the Pacers swept the series, 3-0. Then came the Eastern Conference Finals, when Miller exploded and scored 25 of his 39 points in the fourth quarter of Game 5. The shooting was dramatic enough, but the real theatrics were between Miller and mega-Knicks fan Spike Lee, who jumped from his seat and shouted at Miller. The Indiana guard loved it: He’d shoot a three-pointer, then run past Lee, pointing a long Reggie finger and cursing. He threw in a choking gesture, and came home a hero for standing up to the quintessential New Yorker. “He became Indiana’s player,” says Walsh, now president and CEO of Pacers Sports & Entertainment, “and when we came back to the airport, there were 10,000 people there screaming his name. They saw him as a Hoosier legend.”

“He’s the best professional athlete who ever played in this city,” says the Pacers’ Donnie Walsh. “What he did here, the way he conducted himself, the way he gave back, the period of time that he played.”

Miller’s Hollywood was back—the choke sign-showing, taunt-tossing kid from L.A. There was the time he harassed John Starks of the New York Knicks into head-butting him, and Michael Jordan of the Chicago Bulls into clawing at his face. “Playing Reggie drives me nuts,” Jordan wrote in ESPN The Magazine in 1998. “It’s like chicken-fighting with a woman.” When Shaquille O’Neal knocked over the Pacer who was 6 inches shorter and 135 pounds lighter, Miller bounced up and screamed, “Harder! Hit me harder!” His showmanship could still get him into trouble, like the time he hit what he thought was a game-winning shot against the Chicago Bulls, then took an exaggerated bow to the crowd while the Bulls scored at the buzzer to win. But Miller’s Reggie-ness had long since stopped bothering most of the hometown fans, who were enamored of their star. “He was a loudmouth,” says Tim Donahue, a finance manager from Fishers and longtime Pacers season ticket holder, “but he was our loudmouth.”

Times were good for Miller. He had planned to wait for retirement to get married, but dropped that idea when he met Marita Stavrou, a model and actress from Chicago. He was on top of his game, and his city was on his side. But then, in the span of a year, he twice thought about ditching Indiana. When his contract expired in 1996, he flirted with the idea of heading to, of all franchises, the New York Knicks. But Walsh says he never took the threat seriously, even though he admits he was always a bit surprised when Miller would sign on again. “The longer he stayed here,” Walsh says, “the more he liked it.”

Then came the blow that nearly sent him packing. On May 15, 1997, a fire destroyed the three-story, 14,000-square-foot lakefront home he and his wife were building in Geist. Lost were most of Miller’s memorabilia and his wife’s $45,000 wedding ring, hidden in the house at the time for safekeeping. The fire was ruled an arson, though the investigation led nowhere. Miller’s wife wanted to leave Indianapolis. Miller was mulling it over. That was the summer the Pacers hired a new coach: Bird, who had forged his style in Indiana but never played here professionally. He urged Miller to return to the team. “I had had it,” Miller tells IM. “The fire beat me down a little bit, not knowing who did it, not ever finding who did it, and I didn’t know if I wanted to stick around and rebuild.” Larry Legend, as Miller calls him, convinced him to stay in Indianapolis.

From there, Miller got closer and closer to the NBA championship he coveted. In 1998, Indiana ousted the Knicks in the Eastern Conference Semifinals, and the New York media ran with their “Knicks versus Hicks” jibes. The next year, the Knicks ousted the Pacers in the Eastern Conference Finals in six games. In both series, Miller picked up the mantle for his Hoosiers. “Here, you’re playing for a whole state,” Miller told New York’s Daily News. “Just to see people in overalls come up to you and say, ‘Go, get them boys.’ I like that. I like my chances with my little hick team.” Whether Miller actually saw anyone wearing overalls in Indianapolis, and whether such a person actually approached him, is beside the point. Miller, of Riverside Polytechnic High School and UCLA, of indoor sunglasses and bandannas around his head, not his neck, had identified himself as a hick, and with that, hicks became hip. “He validated us as a sports city,” says Eddie Martin, managing owner of Ed Martin Automotive Group and a Pacers season-ticket holder since 1984. “We’d heckle the New York media at the games and say, ‘Hey, what do you think about those corn people from Indiana now?’”

As Miller aged from mid-30s to near-40 (losing his marriage along the way, in an unpleasantly public divorce that involved legal wrangling over his millions), the Pacers squad transformed from one of the oldest in the NBA to one of the youngest. By the 2001-2002 season, the old guard of Sam Perkins, Rik Smits and Chris Mullin was gone. Young hotshots such as Jermaine O’Neal and Austin Croshere took their places, and to them, Miller became Uncle Reggie, the enforcer, the guy who worked hard, worked them hard and expected the kids to step up to the plate. “Uncle Reg isn’t going to be around much longer,” he reminded them. Last season, Miller’s points-per-game average dropped to 10, matching his rookie season for his lowest ever. Some fans said it was time for Miller to step off the court and into the TV booth, claiming his value as a mentor wasn’t worth his salary. But sentiments changed on November 19 at the Palace of Auburn Hills, when a Detroit Pistons fan threw a cup at Pacers guard Ron Artest, sparking a players-versus-fans brawl that generated enough suspensions to napalm the rest of the Pacers’ season. Miller, who sat on the bench for 16 games early this season nursing a broken left hand, hit the court in the younger players’ absence, averaging 19.8 points in his first 10 games. “He was incredible,” says Larry Brown, the Pistons coach. “He was playing like he was 25.”

“I think Reggie Miller should be given a crown when he leaves here,” says John Mellencamp, the Hoosier rocker who befriended Miller and even featured him in his “Just Another Day” video in 1996. “He did a lot more for Indiana than Indiana ever did for him.” In fact, at times it was difficult to marry the on-court alter-ego of bad-boy Miller, the most hated opponent in basketball, with the Indianapolis legacy of Miller, the man. “He’s the best professional athlete who ever played in this city,” says Walsh. “What he did here, the way he conducted himself, the way he gave back, the period of time that he played. In this city and state, nobody who has played here has done what he did.” Miller supports the burn unit at Riley Children’s Hospital and likes to make unscheduled visits to Indianapolis-area schools. He has been known to occasionally take Pacers ball boys to dinner. He donated $206,000—$1,000 for every three-point shot made in the 2001-2002 season—to the Red Cross Disaster Relief Fund after 9/11, even though he supposedly hated New York. Years ago, Miller was the only person who pulled over on an Indianapolis parkway to help a boy trying to flag down motorists. The boy’s mother was suffering a heart attack, and Miller called authorities on his cell phone and waited with the pair until help arrived.

Hoosiers fell in love with Reggie Miller because he won. Because he played their kind of ball. Because he wasn’t ashamed to be one of them. But mostly because while their kids and grandkids were getting college degrees and moving out of state for bigger cities and bigger paychecks, better jobs and better climates, Miller stayed right here. Fans dispensed with the nickname he preferred, “Hollywood,” which frankly never caught on anyway. Instead, he got a simple chant: “Reg-gie, Reg-gie, Reg-gie.’’

It goes without saying that Miller’s jersey will be retired next season. What’s more telling is that Miller will be the first NBA Pacer to hang his number in the rafters. “We just made up our minds that until Reggie retired, we wouldn’t retire any numbers,” Walsh says. Miller’s will join the retired Pacer numbers of old, the ABA guys—George McGinnis, No. 30; Mel Daniels, No. 34; Roger Brown, No. 35; and longtime coach Slick Leonard. His number will hang at Conseco Fieldhouse, the one NBA venue where fans always gave No. 31 a warm reception. They booed him at all the rest: Madison Square Garden. The Staples Center. The United Center. And, once upon a time, when he came to town unproven and unwanted, even at Market Square Arena.

Photos by John Bragg

This article appeared in the April 2005 issue.