Why The Crispus Attucks Legend Lives On

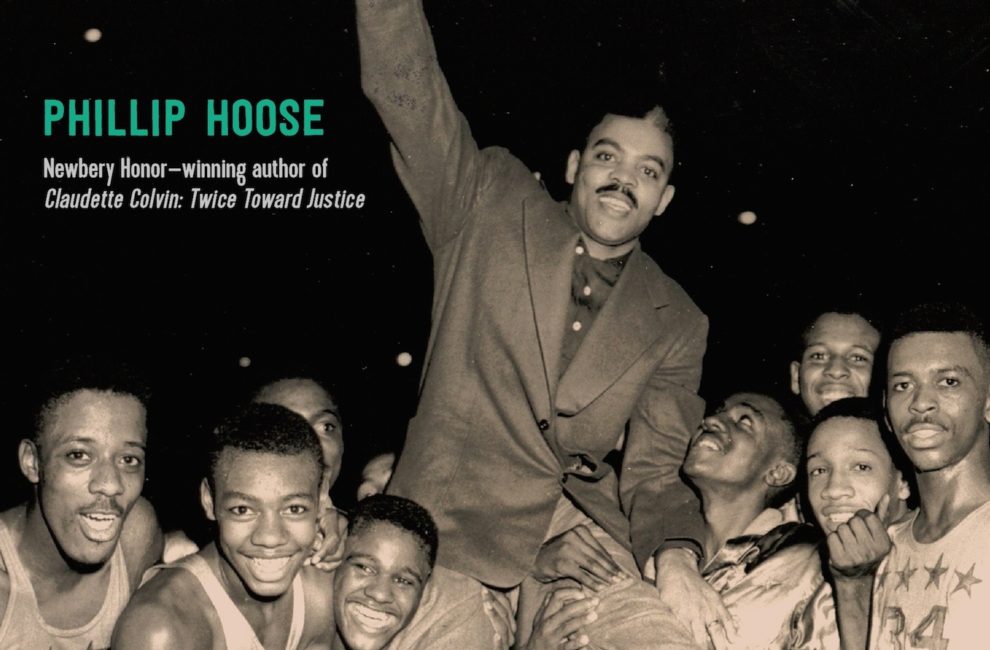

Phillip Hoose’s book chronicles the Crispus Attucks basketball teams of 1955 and 1956 Provided by publisher.

In 1986, on assignment for Sports Illustrated, writer Phillip Hoose came to Indiana to interview basketball legend Oscar Robertson. The stories he heard fascinated him so much, he couldn’t shake them. Decades later, he’s written a book about Robertson, his basketball team, and their place in the Civil Rights movement. Attucks! Oscar Robertson and the Basketball Team that Awakened a City was recently picked to represent Indiana at the Library of Congress National Book Festival, to be held in Washington, D.C., in August.

IM: What did Oscar Robertson say that made you want to write this book?

PH: That the Klan didn’t know what they were doing when they established his school. I said, “What do you mean?” He said the Klan started our school at Crispus Attucks to segregate all the black students and teachers of Indianapolis, but the success of the basketball program later on became so pronounced that there were calls to break up the dynasty—that it was the success of the basketball teams that integrated the public schools of the city. I asked for more information—I’d never heard this. I had gone to school in Speedway, where there was a total of one black student and we knew nothing about this Crispus Attucks High School—it seemed like a mystery place. People didn’t know how to pronounce it—they called it “Christmas Attucks,” not to put the school down, but because we didn’t know anything about it. So Oscar’s statement to me when we had that interview made me want to research all this and put it into a basketball context. I think that Indiana is the only place where that can happen, where you can play out some aspects of the Civil Rights movement through basketball, because basketball was so big more than anywhere else.

IM: What was the most shocking thing that you found out while working on this book?

PH: The extent of the Klan. I found out that my own family contained Klan members, including my grandfather, and that my aunt had burdened her rural property with a clause in the deed that said the property couldn’t be sold to a black, Catholic, or Jew. I have another aunt who told me her first memory was being held in her father’s arms, watching a cross burn near the field down in Carbon, Indiana. I think the thing that opened my eyes is how many people were involved—it wasn’t just a basketball story anymore, it was a story of racial attitudes and the difficulties that Indiana had of accepting people who were not, as they put it, 100 percent white. I think that it surprised me a little bit that you could attach it to basketball, but it should have made sense because Indiana is a place where ideas really catch on. The scale of high school basketball in Indiana was just amazing—something like 13 of the 14 biggest gyms I think to this day in the United States are in Indiana. When Hoosiers bite into something, they bite hard, and the scale of the Klan was that way, too.

Author Phillip HooseProvided by Phillip Hoose

IM: You mention in the book that the Attucks team had no gym at first, and when they did get one, it was so small, players would often crash into the walls. Players got hand-me-down jerseys from Butler that they had to sew up themselves. Did those conditions surprise you?

PH: No, it didn’t surprise me at all, because Crispus Attucks High School was not built with basketball competition in mind. The people who built Crispus Attucks saw the school as a job training school and there was a good academic component to it as well. People never anticipated that there would be a high school basketball team, so they never expected them to compete with other schools in the tournament.

IM: Why did so many Crispus Attucks students go on to find success?

PH: They had an incredible faculty—it was almost like a college faculty at Attucks, with classroom teachers who could speak six or seven languages. It was possible to get a terrific education at Crispus Attucks High school because those teachers were so excellent.

IM: Is it true that Oscar Robertson had the only basketball when he and his friends played at Lockefield Gardens?

PH: There must have been at least one more. Several people describe Oscar’s possession of that ball as the only privately owned basketball in that neighborhood. It put Oscar in a great position when he got it that Christmas because if people tried to tell him to go away, he could say, “OK, I’m taking my ball, too.” When I talked to him, he brought it up again—he said there wasn’t anything else to do—there weren’t any music programs for the summer, things like that. You would just play basketball all the time and that was the way to get prestige in your neighborhood, to be good at that.

IM: What do you hope readers take away from the book?

PH: How much kids, young people, and teens contributed to success in the Civil Rights movement. Oscar Robertson was 16 years old the night that they won the state tournament in 1955. These were all teenagers in American history. Kids are under-credited for some of the things they did. Here in Indiana, it was a weird way to make a statement through basketball, but they did. They made a Civil Rights statement by excelling at something that all Hoosiers valued, which is excellence in basketball.