If James Dean Were Alive Today, He'd Be Dead.

Editor’s Note, Feb. 15, 2013: Hugh Hefner’s personal secretary, Mary O’Connor, was James Dean’s fellow Fairmount, Indiana, native. She died on Jan. 27. Mark Roesler, CEO of CMG Worldwide (headquartered in Indianapolis) manages the intellectual property rights of Dean and other celebrities, and he gave closing remarks at O’Connor’s memorial service on Feb. 8 at the Playboy Mansion in Los Angeles, noting also that the service was taking place on Dean’s birthday. Here, our June 2005 feature story about another Hoosier who went to Hollywood, about Dean’s craft and legacy.

Fifty years ago James Dean plowed his Porsche into the side of another man’s car on a highway just outside Cholame, California, about midway between Los Angeles and San Francisco. Donald Turnupseed had  been driving in the opposite direction and tried to make a left turn across the highway. Dean’s last words, spoken to the mechanic sitting next to him, were “He’s got to see us.” Prescient, he was not.

been driving in the opposite direction and tried to make a left turn across the highway. Dean’s last words, spoken to the mechanic sitting next to him, were “He’s got to see us.” Prescient, he was not.

Dean would have been 74 if he’d lived—by way of comparison, and just for a fright, that’s 10 years older than Dick Cheney. But he didn’t live, of course; instead, he left behind three terrible movies and a reputation as … what? The first … what? The best … what? Poor James Dean. He seems to have been a perfectly nice young man—good Midwesterner, studious, insecure, perhaps a bit of a dupe—who wanted, innocently and like many Hollywood actors, to be taken seriously. It was never going to happen. What he did belongs to the history of celebrity, not film.

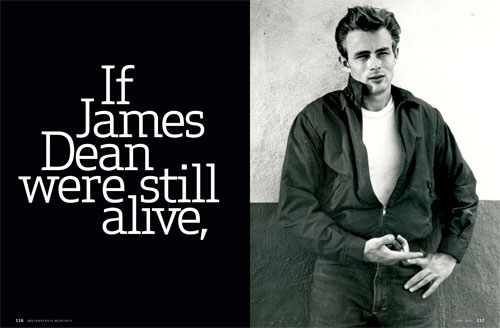

There’s a telling photograph (shown, below right) of Marlon Brando giving Dean the finger, or so it seems; Brando could simply have been getting a bit of sleep out of the corner of his eye (and Rock Hudson was actually straight). The proximate cause of this gesture of disrespect is anyone’s guess, but the animosity behind it is clear enough. “I hardly knew him,” Brando once told Truman Capote. “But he had an idée fixe about me. Whatever I did he did.” Brando knew what almost every American artist of the 20th century has learned: Somebody does it first, and then somebody else does it blander. Dean was a perpetrator of Method Acting the E-Z Way, an icon of rebellion without threat, attraction without sex, suffering without complication. More than that, though, he was one of the most prominent examples of what, for the sake of argument, might be called the White-White Jesus, a strange phenomenon Americans periodically resurrect for purposes of worship, the way we rediscover, from time to time, French cooking or poker nights.

Of course, Dean, white-white though he was, made his name playing the suffering outsider. In reality, he was the outsider who doubled as the consummate insider. He may not have been the first symbol of Misunderstood Youth (Brando beat him to that), but he was the first to participate in the paradox of being both misunderstood and wildly popular, at once outcast and embraced, lowly and exalted, lonely and besieged by acolytes.

And what made this popularity possible? His looks. That’s what people seem to remember about Dean: not that he was a great actor, or a charismatic figure, or even an interesting fellow, but that he was pretty. As surely he was, but it’s a kind of pretty that precludes being sexy, that would be muddied and compromised by anything as carnal as carnality. True, he inspires in his followers a fervency that borders on the erotic, but only by denying the possibility of actual lust. Dean wasn’t trying to get laid—he was trying to be a little California god, and his sexlessness is what makes him holy. Think of a GI Joe doll: Underneath the clothes, the crotch is smooth; there’s nothing there but a hinge to keep the legs from falling off.

In Hollywood Babylon, Kenneth Anger suggests that Dean liked to engage in a bit of erotic business that goes by the all-too-revealing name “human ashtray.” Whether this is true or not we’ll never know, but it works well enough as metaphor, for suffering is Dean’s stock in trade, his brand of sexuality—the only means of transcendence available to him. With Dean, martyrdom substitutes for eroticism. As human ashtray, he gets off on pain and torment, while his audience, believing it’s seeing something less tawdry than mere pleasure, gets off on its own pangs of sympathy. Substitute arrows for cigarette butts and you have a familiar enough image: St. Francis of Assisi, writhing in ecstasy as he expires in pain.

A few months after Dean died, Elvis had his first gold record, and American culture became inescapably miscegenated and sexualized. Never again could a male star get over as an object of gaspy teen desire without being able to shake his hips. Never again would asexuality have quite so much power. In fact, if Dean hadn’t crashed his car, someone probably would have had to kill him.

As for the movies themselves, they’re pretty much unwatchable, except as campy artifacts of an all-too-self-serious age. In Giant, Dean is a ne’er-do-well turned wildcat millionaire with the laughable name of Jett Rink, stumbling around and

doing his best to glower smokily; in Rebel Without a Cause his character bears the hardly more sober name of Jim Stark; in East of Eden he is Cal Trask—an anagram of Stark, as if they had run out of ideas for him, and just rearranged the characters a little bit. They’re all comic-book names, spare and stripped of inflection, as if an extra syllable in a last name would have introduced an element of complexity too great for the actor to shoulder.

That’s not to say Dean hasn’t had his fans. Dennis Hopper looked up to him. Martin Sheen loved him. Andy Warhol adored him. He received two posthumous Oscar nominations (for East of Eden and Giant), a feat no other dead actor has achieved. In 1996, the U.S. Postal Service put his face on a 32-cent stamp. The American Film Institute includes him on its list of the 50 Greatest American Screen Legends. Some 30,000 pilgrims flock to the James Dean festival in Fairmount each year. And Warner Bros. is commemorating the 50th anniversary of his death with a new documentary and a DVD set of his three movies. But Oscar nominations are hardly reliable markers of excellence. And the 50th-anniversary hullabaloo has the distinctive air of cashing in. With Dean, the critical mass of critical acclaim is just not there.

Rebel Without a Cause must be one of the worst movies ever made, a silly stew of nickel psychology that panders to its intended audience so shamelessly, it’s a wonder anyone can watch it with a straight face. Dean’s performance is not so much acting as it is twitching, gibbering, giggling, chewing—anything to disguise the fact that he’s incapable of speaking a single line of dialogue convincingly (though to be fair, no one could say lines like these as if he meant them—“You’re tearing me apart!” “Stop tearing me apart!”)

Well, youth is entitled to its enthusiasms, and Dean and others like him are likely a rite of passage for many young girls—like horses, say, or gymnastics. Nothing wrong with that—in any case, it might be alarming to discover a teenager with an all-consuming passion for Edward G. Robinson or Robert Mitchum.

But few things in this world age as badly as Other People’s Youthful Obsessions, especially those, like Dean, who are trapped in the amber of their first appeal. There is, after all, something unusually distant about his achievement: It belongs to another world, not this one. Sid Vicious died in 1979—26 years ago—but if he showed up tomorrow he would still have a place in the life of our culture; he seems perfectly contemporary that way. In ’79, James Dean had been dead for 24 years, and even then he was so far removed from things that it was difficult to imagine he’d ever been new at all.

And what if he had lived? It’s impossible to say, of course, but one can predict that it wouldn’t have been pretty. After Elvis there was little room for White-White Jesuses, and it seems plausible that Dean would have ended up something like Jack Kerouac: a drunken reactionary incapable of understanding that, in helping to create youth culture (as self-contradictory as that phrase seems now), he’d unleashed a monster that turned around and, without the slightest hesitation, scarfed him up.

So what could Dean do, except die? Only one of his movies was released before he crashed the car; the others came out the following year, with all of Hollywood’s hype and legend-making apparatus behind them. Give the guy this: He had a fine sense of timing. Think what he managed to avoid: the years of unemployment, the jokes on late-night talk shows, the cameos—“Hey, isn’t that what’s-his-name from that movie with Natalie Wood?” Pauline Kael once wrote that Dean’s death spared him becoming “just another actor who outlived his myth and became ordinary in stale roles.” Instead, he gets his image on velvet paintings, and a reputation he can never disappoint. Poor James Dean. He was the hero who never was, and dying was the only thing he ever did well.

Photos courtesy James Dean Gallery; illustration by John Perlock.

This article appeared in the June 2005 issue.