Murder, She Wrote: The LaSalle Street Murders

Editor’s Note: The following originally appeared in the September 1996 issue. Co-author Bettie Cadou was a longtime reporter for The Indianapolis News and taught journalism at Butler University and IUPUI. After her death in 2002, she was inducted into the Indiana Journalism Hall of Fame. Brian D. Smith is a former IM senior editor.

The saga began routinely enough: Robert Gierse, 34, and Robert Hinson, 30—two businessmen known to be hardy partiers—didn’t show up for work on the morning of December 1, 1971. Then morning turned to afternoon, and, when calls to their home and other likely hangouts yielded no sign of the pair, a business associate decided to check their house at 1318 North LaSalle Street.

He found them, all right: throats cut, hands and feet bound with strips of sheets. Also in the house was their friend James Barker, 27, who’d suffered the same grisly fate. The call to the police sounded so surreal that the dispatcher sent one officer to investigate. He spent only moments in the house before dashing to his patrol car, heart pumping. “Send me 83 [homicide],” he barked into his radio. “Send me identifications, send me a coroner, send me superior officers—we’ve got a triple murder!”

The dispatcher sent a legion of investigators, but none could solve the case that came to be known as the LaSalle Street murders. No suspect confessed, no one was convicted or even arrested, nor did any witness with significant information come forward.

Winter came and went, as did spring, summer, and fall, and 18 more like them. By 1991, the LaSalle Street murders occupied a small place in local lore: a seemingly perfect crime that had once kept an entire city in suspense, but was barely remembered now.

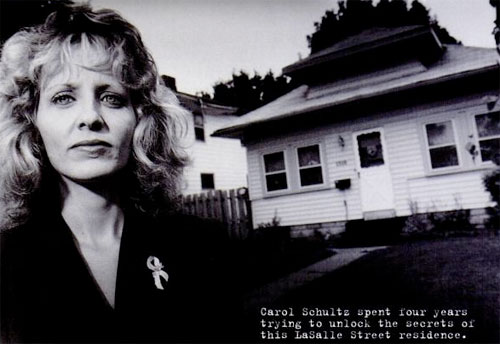

That March, however, the case resurfaced. Like a forest fire, it began as a small spark, igniting the recollection of an occasional Indianapolis News correspondent. Her name was Carol Schultz, and she was used to writing feature stories on topics such as peas and sunflowers. Had she been content to continue writing about peas and sunflowers, hardly anyone in 1996 would be thinking about a triple homicide that occurred in 1971.

But Schultz also became interested—no, obsessed—with the LaSalle Street murders, and by the time her obsession ran its course, it had consumed nearly four years of her life; led to two men’s indictments on murder charges; cost Schultz her part-time writing job; and left her and nearly everyone connected to the case with enough egg on their faces for a Denny’s breakfast.

Changing from home-and-garden writer into dogged sleuth, Schultz scavenged the long-buried secretof LaSalle Street and retrieved enough curios to put the old case (and herself) in the news. Her efforts could have launched her journalistic career; could have brought the unknown killers to justice; could have cracked one of the greatest murder mysteries in Indianapolis history. But when her unbridled enthusiasm trampled the rules of ethics and evidence, the case she helped craft self-destructed before it even came to trial.

In a May 1996 hearing to set bond for one suspect, Marion Superior Judge Paula Lopossa declared, “The court finds that the investigation was compromised by the meddling of Carol Schultz, who is a very biased former investigative reporter.” Hours later, Marion County prosecutor Scott Newman moved to dismissed the case, calling it “impossible to prosecute” and adding, “There is absolutely no hope of conviction.”

It all seemed clear enough: An over-exuberant writer built a case that collapsed onto its own shaky foundation, leaving a coat of grime on the reputations of those who believed her. Yet, like almost everything else in this quarter-century-old saga, even this conclusion can’ t necessarily be trusted.

Moreover, even as LaSalle Street slips back into history, a smaller mystery-within-a-mystery remains: Who was Carol Schultz, and how did she single-handedly resurrect one of Indianapolis’s most notorious unsolved crimes?

Carol Schultz at the LaSalle Street home.

Schultz can’t easily explain the lure of LaSalle Street, or why her life came to revolve around the lives and deaths of three eastside businessmen from the ’70s. “It just intrigued me,” she says in a classic understatement.

While few people would have tackled the mystery with such fervor, there’s no denying its JFK-like complexity. Within a week of the murders, investigators concocted a spectrum of possible motives, including: (1) an ex-husband or ex-boyfriend was enraged that his beloved was dating one of the men ; (2) a former employer of Hinson and Gierse had $150,000 life insurance policies (set to expire in two days) on them; (3) Gierse and Hinson, who operated a microfilming business, had resisted a mob effort to control the industry; and (4) Hinson knew too much—i.e., the killer or killers of a fourth man, John C. Terhorst, whose body was found in Eagle Creek months earlier.

The jealous “ex” scenario seemed especially plausible when authorities learned that the trio, all single, had engaged in a contest to see who could bed the most women. According to one source, the three had amassed a cumulative score of 63 at the time of their deaths.

In a strange way, their sex appeal persisted beyond the grave. “I was attracted to these great-looking guys who were my age, guys who romanced all these women,” says Schultz, 34. “I have to admit, if it had been three fat old women, I don’t think I’d have been that interested.”

Her involvement began in low-key fashion: In March 1991, the News correspondent was assigned to write a story about Unsolved Mysteries taping a program in Indianapolis. That might have been the end of it, but Schultz expanded on the idea. “I thought, wow, it’d be really great to do a sidebar on ‘What’s Indianapolis’s biggest unsolved mystery?’ I was laying on that waterbed in that room in there,” she says, pointing toward the back of her modest southeastside home, “and I remembered my dad talking to me about LaSalle Street when I was a little girl.” After realizing the crime had occurred almost exactly 20 years earlier, she got an editor’s permission to do an anniversary story on the slayings. Despite having only a medium-length story to write, she treated the assignment like a doctoral thesis.

Her interview with Indianapolis Police Department Lieutenant Michael Popcheff, who had investigated the crime in 1971, led to weekly one-hour conversations with the officer at a nearby Waffle House, Schultz says. By her account, after one meeting, as Popcheff was preparing to pay the bill, he suddenly turned to her and said, “You know, there’s been a new clue in this case. It’s a one-in-a-million shot, but why don’t you mess around with it?”

The one-in-a-million shot was more like a shot in the dark: A former waitress at the now-defunct Tommy’s Starlight Palladium had recently talked of seeing a man with “dark, evil, crazy eyes” enter the bar on the night of the murder. This matched a young Bible student’s description of a man in a parked car on LaSalle Street that night.

Schultz says she found and interviewed the Bible student (in Michigan), the former waitress (working at a laundromat), and relatives of the victims. Each week she would report back to the officer, drawing increasing respect, Schultz says. “He’d say, ‘Wow, I can’t believe you’re finding these people,” she says. “It was a pat on my back, kind of like having a story on the front page.”

The assignment took on a life of its own, existing more for its own sake than for any long-term goal of cracking the case. “It wasn’t that I was so focused on solving the murders,” she says. “It was the adrenaline I was hooked on, and it was making me physically better.”

Health has been a lifelong concern for Schultz, who was born with serious liver problems that have periodically resurfaced. She talks of being in and out of hospitals since childhood, which limited her aspirations of becoming a journalist. Older sister Dianna Kincaid, a local real estate agent, recalls Carol as a child with relentless “show-me” curiosity. “As a little girl, if you told her she would get hurt doing something,” says Kincaid, “she had to find out for herself that it was going to hurt.” Their mother once told young Carol not to jump off the coffee table onto the couch, lest she hit her mouth. But Carol, who had to find out for herself, did just that, cutting her chin. The scar remains to this day.

As a teenager, the former Carol Caldwell attended Creston Junior High and Warren Central High School, worked on the school newspaper and earned a scholarship to Ball State University, Schultz recalls. But she quit school as a l6-year-old junior, got a job as a waitress and married her boss, a man six years her senior. The couple traveled around the country in a van, working as a waitress and grill cook, but her pregnancy sent them back to Indianapolis, where Schultz took a job as a keypunch operator. The experience prompted a still-present quirk: the ability to summon telephone numbers from memory by punching an imaginary touch-tone pad in the air.

A son was born, but their marriage didn’t last, and in 1984 Schultz resumed her quest for a writing career. She passed the GED and enrolled in journalism classes at IUPUI, twice winning a Thomas R. Keating Award from the IU School of Journalism. Former IUPUI journalism professor Dennis Cripe, now at Franklin College, recalls her as a high achiever. “I was impressed with her work,” Cripe says. “As an advisor to the new students, I held Carol up as a good model for the kind of writing we should have.”

While Schultz never got a bachelor’s degree (she blames health problems), she at least managed to find correspondent work with The Indianapolis News. The money wasn’t great, perhaps $25 per story, but like many at her experience level, she was treading the well-worn path of apprenticeship.

Yet, like the child who always had to find out for herself, Schultz had long pushed beyond the usual parameters of her writing assignments, interviewing 10 sources when two or three would do. “I was never satisfied with a little 12-inch story,” she says. “I always felt I had to do the biggest, the best, the most.” It was more than the usual competitive drive; Schultz wanted to do an “in-your-face” on a lifetime of naysayers. “I had so many doctors tell me I was terminal, that I was going to die, that I was a nothing and a nobody because I was handicapped,” she says, “that I had to prove to myself that I could write the best story, have the best sources. It was a personal challenge.”

Ambition met opportunity on LaSalle Street. Given a crime story with a bottomless pit of possibilities, offering a challenge that no one had surmounted, Schultz persevered like the Energizer bunny. Despite her sparse income, she utilized every resource she could muster. She conducted hundreds of interviews, many with sources out of state, but avoided a massive telephone bill by placing calls through the Star/News switchboard, Schultz says. She retrieved every newspaper story available at the Central Library. She drove by the bars the victims used to frequent. And when she could think of nothing else, she went to the crime scene. “I’d drive by the death house and sit and wonder,” she says.

Even tangential topics caught her eye. “The guys were Masons,” she notes, “so I got books on the Masons and read them.” Actually, the guys were barely Masons—Gierse and Hinson had just been inducted into the Broad Ripple Masonic Lodge, and Barker was awaiting the same ceremony, but no matter. “It was my illness that was driving me: Adrenaline is healing,” she says. “I became obsessed with the healthiness I was feeling as a result of this case.”

And she became obsessed with finding a man with dark, evil, crazy eyes. Told that a local newspaper reporter had once identified two men as the most likely perpetrators, she dug up the old article. The first suspect was a deceased underworld figure, while the second was a still-living reputed Teamsters thug with unusual dark eyes.

Bingo—Schultz had her man, or so it seemed. She sent her entire file to Unsolved Mysteries, and was excited to learn that a film crew would return to Indianapolis in the fall of ‘91 to tape a segment on LaSalle Street. Meanwhile, she even located the dark-eyed suspect in a remote fishing village in Florida. Schultz could picture it all: Once Unsolved Mysteries aired the story, she would call the FBI and have agents surround the man’s house.

She kept his picture on her refrigerator for more than a year, and her house teemed with boxes and files on the case. But the solution to her personal game would prove tougher than “Colonel Mustard in the conservatory with a lead pipe”—especially after police said the dark-eyed Floridian was not a suspect.

Carroll Horton

Schultz’s editor at The News, Mark Ridolfi, had long since tired of the topic. When she tried to pitch him one more LaSalle Street story, he demurred, saying the newspaper could do only so many articles on the subject.

Regardless, her search went on. Her police contacts gave her access to intimate information—including the names of the victims’ ex-lovers. Schultz says she found several of them, but was stymied in her attempt to locate Gierse’s ex-girlfriend, Diane Horton. Then a former secretary with the microfilming firm put Schultz in touch with Diane’s ex-husband: an elderly engine shop owner named Carroll Horton.

Schultz called him, and the conversation immediately turned to LaSalle Street. She felt an instant affinity with Horton, a man who reminded her of her late father.

“I have memories as a little girl of riding in the pickup and going out to auto parts stores,” she says.

Horton won’t comment on the case, so details of their phone conversations come entirely from Schultz. As she tells it, however, Horton told her he had ESP, and she was all ears. “You do?” she replied. “Really? All my life I’ve had dreams that have come true and have always been interested in ESP.”

Then Horton told her, “My ESP is telling me right now that you’re going to be the one to solve this case. Stick with me and I’m gonna help you win the Pulitzer Prize.” Schultz was delighted.

“This was the first time I’d met anyone as interested as I was in the LaSalle Street murders,” she says. “He became my new best friend.”

Schultz says the two began chatting daily about the case, for which Horton showed intense interest. “He wanted to know everything I was doing: who I talked to, when, what they said,” she says. “He was so easy to talk to, and he reminded me of my daddy.”

The budding relationship reveals Schultz’s dichotomy: a relentless reporter with a touch of unworldliness. Julie Slaymaker, former president of the Woman’s Press Club of Indiana, concurs. Acknowledging Schultz’s dedication, she says, “I would describe her as vulnerable and perhaps a little naive.”

Floyd Michael Chastain said he took part in the murders – then said he didn’t.

Schultz’s father figure pointed her to another possible source, Floyd Michael Chastain, a convicted murderer incarcerated in a Florida prison. In the summer of 1992 she wrote him a letter, and on September 1, 1992, Chastain called her collect. “Ma’am, I got your letter,” he began. “This is very serious, because I know who killed the men on LaSalle Street.” Chastain then tried to convince Schultz to fly to Florida, but she insisted her editor wouldn’t let her.

Schultz says she pressed him to tell her the murderer’s identity. “What does he do for a living? Does he work on cars like you?” she asked the former Mars Hill mechanic. “Yes, ma’am,” Chastain replied. “Is it? … It’s not …” she said, choking on the name. So Chastain said it for her: “Carroll Horton.” And suddenly, Horton’s intense interest in the case seemed to make chilling sense.

Chastain later told Schultz that he, Horton, and three other men broke into the house early on December 1. Chastain said he killed Hinson and Horton killed Gierse; he wasn’t sure who killed Barker.

His characterization of Horton contrasted that of a 1996 Star story, which identified him as an Indianapolis 500 chief mechanic in the ’60s who “developed several revolutionary engine designs.” What it didn’t mention was Horton’s darker side: an arrest record that dated to 1953, according to court documents. Through the years, Horton incurred a range of mostly minor charges ranging from defrauding a hotel keeper to child molesting (although several charges, including molesting, were dismissed). Some raps stuck: From 1985 through ’86, Horton served 19 months for a three-count theft conviction.

Schultz knew none of this at the time, but Chastain’s allegations pushed her over the line between reporter and eyewitness. Within two weeks of her chat with Chastain, Schultz took her information to the authorities. “I was a reporter, yet still a citizen,” she explains. “I surrendered information I thought was important to the case while trying not to compromise my work as a journalist.”

But the compromise was well under way. Her conversations with sources took a decidedly unprofessional turn, as terms such as “I love you” escaped her lips and Chastain’s during their conversations. Schultz says she felt only friendship for Chastain, but he seemingly had deeper affection for her, as evidenced by the correspondence he sent her (characterized in court records as “love letters”). “I’m sure he had fantasies,” she says, “but I never led him on. I said, ‘I love you. I love you as a Christian.’” Even so, her behavior was hardly the conduct of Woodward and Bernstein.

Then again, although Judge Lopossa characterized her as a “former investigative reporter,” Schultz had done no previous investigative work for the News before her foray onto LaSalle Street—and even then, she wasn’t supposed to do anything resembling investigative work. Accordingly, Schultz might not have realized she was venturing across the bounds of journalistic protocol.

At any rate, after viewing LaSalle Street as intriguing drama, Schultz suddenly became one of the lead actors. Abandoning any semblance of professional detachment, in October 1992 she complied with a police request to wear a hidden microphone and to pass along information she knew was bogus: that Horton’s fingerprints were found inside the LaSalle Street home.

This was more than enough for Ridolfi, who fired her as a correspondent. It didn’t stop her from writing about LaSalle Street. Having spurred the investigation, Schultz jumped back over the journalistic fence, writing freelance articles for the alternative newspaper Nuvo Newsweekly.Her stories all but urged the prosecutor’s office to take action on the case. “Marion County Prosecutor Jeffrey Modisett has vetoed [Sheriff Joseph] McAtee’s urging to at least bring the case to a grand jury, claiming his ‘witnesses are not credible,’’’ she wrote in 1993. “Why are requests from a sheriff with 30 years in law enforcement ignored at the prosecutor’s office?”

Schultz also contacted the Vidocq Society, a Philadelphia-based organization of about 300 elite specialists who volunteer in the investigation of unsolved homicides.

Vidocq agreed to take the case, offering suggestions to McAtee—who had originally investigated the murders—and Popcheff.

The organization, however, began harboring doubts about Schultz, says Vidocq ‘s Richard Walter, a forensic psychologist. Walter says he warned Schultz not to get overly close to sources, but she paid no heed. “Dealing with her is like trying to herd a group of cats down a driveway,” he says. “I’m uncomfortable, quite frankly, of working outside law enforcement circles, and I was getting more and more concerned about Carol.”

The once-dormant case had already begun popping again. Not only did investigators fly to Florida to interview Chastain, but in a momentous development, a woman who claimed she was in the house during the slayings came forward. She was interviewed, then hypnotized, reportedly corroborating Chastain’s account of the killings. Even so, Modisett wouldn’t present the case to a grand jury.

But by January 1995 it didn’t matter. Having lost in the 1994 election, Democrat Modisett was replaced by a new prosecutor, Republican Scott Newman, who promised to move the case to the front burner. Evidently he did: On March 22, 1996, a grand jury indicted Horton, 70, and Chastain, 44, on three murder counts each, nearly a quarter-century after the triple slaying on LaSalle Street.

It was the day Schultz had anticipated, even prepared for. She had stowed two bottles of champagne in her mother’s refrigerator, and planned to hire a limousine to celebrate the outcome. And for a while, she basked in the glow of her efforts. After years as an obscure feature writer, Schultz was now doing nationally televised interviews. “It was the highest day of my life,” she says. “I had worked for something and it was like, ‘I told you so, America.’” But by the next day, Schultz felt less gratified. “I didn’t want to celebrate,” she says. “I felt sad, guilty. I laid in bed and bawled. I knew I had betrayed him [Horton] probably in a way that no one had ever betrayed him.”

The wheels of justice rolled forward, but they soon fell off. Investigators were already batting with two strikes against them: Much of the physical evidence was destroyed in 1986 (one officer called it a “stupid housecleaning mistake”).

Worse yet, Chastain, a loose cannon from the start, began raining friendly fire on the prosecution. The convicted murderer admitted he told at least five versions of the story, including the most outlandish: that then-President Nixon and labor boss Jimmy Hoffa conspired to commit the murders. Chastain claimed he attended a meeting with Hoffa and then-presidential advisor Charles Colson, and that Nixon wanted Hoffa to collect incriminating microfilm from the victims. Echoing the thoughts of many, Lopossa called the tale “incredible.”

Nor did Schultz come away with reputation intact. After doing interviews on national TV with Dan Rather, she found herself ridiculed in her hometown press. Chastain’s bizarre testimony—that he’d fallen in love with Schultz and hoped to marry her—served as fodder for Star columnist Dick Cady, who implied that both Chastain and Horton were in love with her. As a court hearing approached, Cady wrote: “It could be the first time a judge has to decide whether love really is never having to say you’re sorry.”

Schultz took another hit when she testified that she was offered a movie contract. She said a company called Dream City Films contacted her about the possibility of doing a movie about her LaSalle Street investigation. Schultz signed the contract, which pledged to pay $150,000 if Horton were convicted, but in the end received one check for $900.

Judge Lopossa took a dim view of Chastain’s testimony and Schultz’s role in the investigation, particularly after learning that the writer had seen police files on the case. The judge alleged that Schultz used the files to feed Chastain information that he parroted when interviewed by investigators. Schultz, however, calls the charge “a lie from the pit of hell,” saying Chastain already had intimate knowledge of the slayings.

If Chastain had any credibility at that point, it could’t have survived the disclosure of a letter he wrote to Horton (a copy of which went to an Indianapolis police detective) in December 1995. Chastain’s correspondence, filled with misspellings, declares that neither he nor Horton was involved in the LaSalle Street murders: “I am sorry, but I have lied all a long. Trying to get my self out of prison, down here. And get a ride home to see my family … I was not there. Never was.

“Well old buddy I sorry I lied on you,” Chastain continued in a postscript, “but I did get to come home, eat real good.”

Nor could the prosecution depend on the woman who said she saw the murders. Not only was she an alcoholic, Newman said, but the fact that she’d been hypnotized cast doubt on her recollections.

So that was that: The star witness was a liar; the other witness was an inebriate; the freelance writer was unprofessional; the prosecutor was out of ammo; and the suspect was free. And just as in 1971, whoever really committed the LaSalle Street murders had gotten away with it.

- But any attempt to tie up this package with a red ribbon leaves a few corners sticking out. Consider these quandaries:

Police admittedly lied to Horton when they told him, through Schultz, that his fingerprints were found in the home. Yet, according to officers, Horton claimed he was allowed to enter the house briefly as investigators probed the crime scene. Police insist that Horton never entered the house—so why would he say he was there? - McAtee (who will no longer comment) said in 1993 that Chastain knew details only a perpetrator could have known. Other investigators privately agree, saying they still consider Horton the most likely suspect. Chastain is an admitted liar—but was he lying when he said he was involved in the crime, or when he said he wasn’t?

- In 1993, while still claiming to have participated, Chastain reportedly passed a lie-detector test in Florida.

- Schultz’s tires were slashed on April 28, the day before her deposition. If her investigation was off base, who would have reason to threaten her?

- Of all the twists in the case, the most preposterous-sounding is the alleged Nixon-Colson-Hoffa connection. Yet in a May 1996 letter to the court, Gierse’s brother Ted wrote, “My brother did meet and knew Jimmy Hoffa (Chicago 1966).”

Whatever is true, nothing about the current status quo feels completely satisfying. If Horton didn’t commit the crime, he wasted a month of his life in jail and was publicly branded a triple murderer. And numerous public servants will have spent countless hours and dollars chasing a 25-year-old wild goose from Indy to Florida and back.

If Horton did commit the crime, the utter collapse of the case makes it all but certain that he will never again be charged, let alone convicted—and ironically, Schultz, who originally hoped to solve the case, will have contributed to that outcome. On the other hand, if Horton is guilty, those who revere justice might take some solace in the fact that, by helping to put him behind bars for even a month, Schultz accomplished more than any police officer or prosecutor ever did.

If nothing else, Schultz can take credit for persistence. “She was obsessed with the case,” says Vidocq member Fred Bornhofen. “We recognized that and told her repeatedly that this is the wrong approach, that you have to be objective and professional about it,” says Bornhofen. “On the other hand, she showed us a thing or two about digging up evidence, and that too should be recognized. Every roadblock was placed in her path—lost physical evidence, lack of interest by the first prosecutor—yet she kept on going.” Vidocq’s Walter, however, contends Schultz went too far: “She ruined the case primarily by unprofessional conduct, leading Chastain and Horton on.”

Whatever once possessed Schultz has turned her loose. “The obsession is gone, the desire to prove I was right is gone,” she says. “I will never, ever pursue the LaSalle Street investigation again.”

But she doesn’t believe she was wrong. “For three years and nine months it was a hell of a game. And I was the only one to give him a run for his money in 25 years,” Schultz says of Horton. And while Chastain is an admitted liar, she still thinks he was telling the truth when he implicated himself in the murders. “Floyd Chastain lied about some things,” she says, “but I always knew when he was lying. I could tell by the change in his voice.”

The logical question is why Horton, if indeed guilty, would steer Schultz to Chastain. She contends that keeping tabs on her investigation gave him a pipeline to the police probe. In any case, Schultz says she’s glad the experience is over, adding that she no longer has faith in the American justice system.

On the wall of her mother’s kitchen is a plaque from Vidocq. presented to Schultz before the murder case came apart. “Everybody looked, but only you saw,” reads its inscription.

Did Carol Schultz really see anything—besides the fantasy world of a liar who wanted to “come home (and) eat real good”? As an investigator once told her, “Whores can be raped and liars can tell the truth.” Heaven knows whether rookie reporters can track down triple murderers on the first try.

This article appeared in the September 1996 issue.