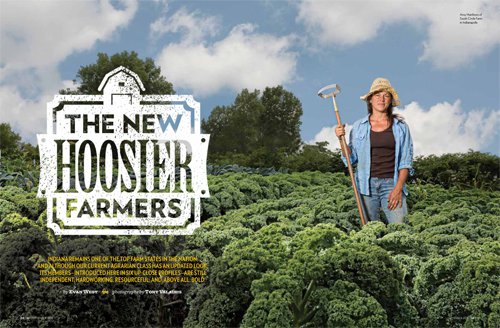

The New Hoosier Farmer: Is Kind of a Big Deal

He drops the name casually and without affectation. Kip Tom is recounting a forum he attended in Washington, D.C., as Congress debated a new farm bill, and you’d think he had just run into a co-worker at the office water cooler. “You’ll find this to be true with most of the new farmers: We don’t like to be subsidized,” he says. “I had this conversation with the secretary of agriculture about two weeks ago.” That is, U.S. Secretary of Agriculture Tom Vilsack, who stands nine places behind the president in the line of succession. “He said, ‘What can we do for you, Kip?’ And I said—you probably won’t want to put this in your article—‘You need to get the hell out of our way. Let private industry do what it does best: conduct business.’”

Okay, so Kip Tom is on a first-name basis with the nation’s top-ranking ag official—not bad for a Hoosier farm boy who started out driving a tractor. Having a 20,000-acre spread, one of the largest farms in one of the nation’s most productive farm states, buys some clout.

“People think we’re still running around in bib overalls, riding a tractor all day, throwing a little seed in the ground,” he says, steering his mud-splattered Ford F-150 onto a county road near Leesburg, in far-northern Indiana. Yes, Tom does drive a pickup—a sweet white crew cab that rides like a Cadillac and has power running boards that lower to meet your feet when you pull on the door handles. And he is among the 97 percent of Indiana’s grain-growers who raise corn and/or soybeans. But he’s quick to distinguish himself from “Joe Farmer,” a name Tom uses to evoke the stereotype of the agrarian rube. Joe Farmer starts the morning milking cows; Tom reads The Wall Street Journal. Joe Farmer chews the cud down at the diner; Tom compares notes with executives from medical-device companies in nearby Warsaw. Joe Farmer can fix a fence with baling wire; Tom earns consulting fees giving ag-industry advice to hedge-fund managers in San Francisco and London. “My concerns are macroeconomic,” he says. “I’m not worried about the local corn prices up here. I’m worried about what’s happening in the EU.” He recently joined Howard Buffett—son of the fourth-richest man in the world—on a mission to address agricultural development in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Tom, 58, grew up helping his parents work 200 acres, some of the same land the family had farmed since 1837. As a young man, he dreamed of greener pastures, so he left the farm for college, hoping to become a lawyer. But in his first semester, his brother Kevin was badly injured in a car accident, and Tom returned home to be with his family. His brother died eight weeks later; Tom stayed on the farm.

Now, Tom Farms spans seven counties. And Tom stands at the forefront of a trend that, for nearly half a century, has seen the number of big farms grow faster than a cornstalk on a balmy July morning. According to the U.S. Census of Agriculture, the state had about 50 farms larger than 2,000 acres in 1974; in 2007, there were nearly 1,300. Since then, according to USDA estimates, the highest-grossing Indiana farms have increased in number by 44 percent.

A lot of that growth has come at the expense of farmsteads like the one Tom remembers from childhood. The plight of America’s small farmers is not news; you might remember the 1980s, Farm Aid concerts, and John Mellencamp’s protest song “Rain on the Scarecrow.” A decade earlier, Secretary of Agriculture Earl Butz (an Indiana native and former ag-school dean at Purdue), buoyed by high grain prices and a strong export market, had announced that U.S. farmers should “get big or get out.” Many took up the call, taking out high-interest loans to acquire acreage and equipment. It was around that time, in the ’70s, that Tom’s family decided to adopt the farming-as-business model, and he remembers a man from Purdue coming by the house to extol the virtues of recordkeeping. Shortly after that, what is now known as Tom Farms began keeping handwritten figures in a dog-eared ledger book.

When commodity prices withered, overextended farmers were stuck in the mud. In the 10 years following 1982, Indiana lost more than a thousand 200-acre farms—a quarter of them. The blood, as Mellencamp sang, was on the plow. But farmers positioned to weather the financial drought were able to buy up cheap land and take over leases left behind by operators who’d bitten the dust. By 1995, Tom Farms controlled more than 3,200 acres.

Mechanization—widespread as early as the 1930s—helped make consolidation inevitable: Simply put, farming now requires fewer hands. And you don’t have to look any further than Walmart to know that big businesses have inherent advantages. “With economies of scale, you can spread your fixed costs over more and more units,” says Chris Hurt, a professor of agricultural economics at Purdue. With their lower cost of production, already-large farmers can outbid smaller competitors when land and leases become available (which isn’t often), making it hard for the little guys to scale up their operations.

“1,500 acres?” says Tom. “That’s a part-time job.” A new tractor can cost $200,000 or more, a combine twice that much; Tom reckons working a smaller farm is barely worth the financial risk. He spends upwards of $10 million annually just on new equipment—15 tractors and three combines in 2013 alone—for about the same price per machine as smaller farmers later pay for his year-old models.

Through the window of Tom’s office, on the farm’s original footprint, he can see the beef cattle his dad, 85, still raises on a small pasture outside. Here, Tom keeps an eye on three computer monitors and an iPad, a tool he carries as religiously as Joe Farmer might a pocketknife. “We’re at the convergence of three innovations in agriculture,” Tom says. “Biotechnology is the first. The second one is the ability to remotely monitor, sense, and control. And the third is informatics. So you’re taking everything you’ve got with one and two, putting them together, and making sound decisions.”

Satellites and cell towers have allowed Tom to turn the farm into a factory without walls. Soil monitors linked to his computers detail moisture levels and other field conditions. A 42-inch LCD screen on the wall over his desk displays a satellite map with a web of color-coded waterlines and brown circles showing the coverage area for each of 100 irrigation pivots. Joe Farmer prays for rain. Tom clicks a mouse.

He holds up his iPad to illustrate what is known as “site-specific” farming. Infrared satellite imaging has generated a green biomass index (GBI) reading on one of his fields, and algorithms translate the data into a script that dictates how much liquid

fertilizer or other chemical the driver should apply as a tractor—equipped with linked computers and an iPad mount—navigates rows of corn or beans.

Three new 13-story grain bins rise from a perfectly manicured cornfield across the road from Tom’s office, like gleaming beacons of agricultural commerce. He can store 2.5 million bushels of corn and soybeans there, allowing him to study the market and determine when and where to sell his product. An unmanned check-in station weighs, scans, and catalogs the grain hauls of semi trucks as they enter the complex. “Used to be that Joe Farmer would pull up, talk to a secretary, and have a bag of popcorn while trucks lined up behind him,” Tom says. “It’s not like that anymore.” He has a futures analyst in Chicago; when international prices are favorable, Tom trucks grain to a train loader, where it is transported to Norfolk, Virginia, and then shipped overseas.

Tom Farms is also one of the top seed-corn producers for global agri-giant Monsanto. Raising the genetically modified crop requires tightly controlled in-field pollination, plus logistical know-how that only operations like Tom’s can provide. Making sure each plant is properly detasseled takes two passes by specialized machines, plus a final “rogueing” step, whereby 700 orange-hat–wearing migrant workers from Latin America and Cambodia walk every row of about 5,000 acres and remove any remaining tassels by hand.

“Monsanto” and “GMO” might be dirty words among the activist crowd, but it probably goes without saying that Tom regards them a bit differently. “The reality is, we’ve served 17 trillion meals with GMO since 1996, and not one documented hospital stay,” he says. The world population is expected to exceed 9 billion by 2050; the International Grains Council projects that global demand will outstrip supply over at least the next four years. “We have to do more with less, and the only way we get there is by applying science and technology,” says Tom. “A lot of people have this view of a white picket fence, a green pasture, and a few cows and chickens—a simple lifestyle. But the reality is, we are manufacturing plants that produce food, fiber, and energy.”

This article appeared in the September 2013 issue. Read about more New Hoosier Farmers here.