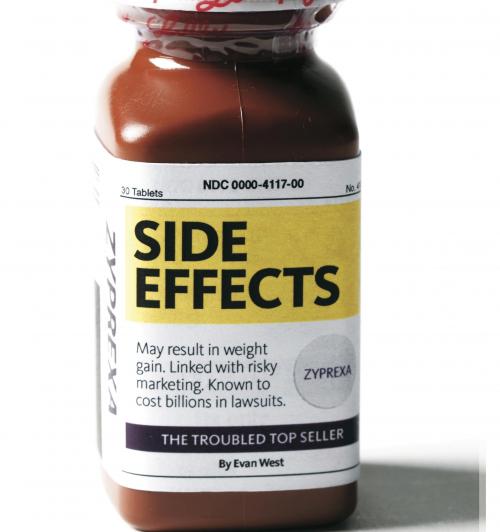

Side Effects

Rob Liversidge was a bright and talented adolescent who by age 18 had enrolled at Cornell University, planning to major in English. But partway through his freshman year in 1981, he fell into a funk so deep that on the worst days, he was unable to get out of bed. His studies suffered, and before the end of the academic year, at the suggestion of a dean, he returned home to Philadelphia, where he spent several months in psychotherapy.

In 1983 he returned to Cornell, but when he came home after the fall semester, “he was in a lather,” recalls his mother, Ellen Liversidge. The words came fast when he spoke, and he seemed to be in a constant hurry. He had sold his drum set—which surprised his mother, because he was an excellent drummer—and used the money to buy a junker of a car. He told his mother that he planned to drive it across the country to a Zen meditation center in San Francisco.

Ellen Liversidge had never known him to behave so erratically. “He was taking terrifying chances,” she says. “His judgment just wasn’t very good. He drove over the Rocky Mountains, in January, with bald tires.”

Her son made it to San Francisco, bald tires and all, but shortly after he arrived he gave up on meditation and started drifting. He spent the next couple of months crisscrossing the southwestern United States in his old jalopy, sleeping on friends’ sofas. To his mother, the trip seemed less like a soul-searching journey than a rambling misadventure.

Then came the phone call. It was Rob, calling from a hospital in San Bernardino County, California. A few days earlier, he told his mother, his car had run out of gas, and he had run out of money. He recounted how he had started banging on doors and ranting nonsense at anyone who answered. Authorities had picked him up, and he had been in the hospital, heavily sedated, ever since. It was his first full-blown psychotic episode.

Over the course of the next 15 years, Rob Liversidge would live what you might call a “typical” life for a person with a psychotic disorder—a life burdened by alternating periods of lucidity and personal crisis, elusive and changing diagnoses, and numerous drug regimens. In 2001, a psychiatrist in Maryland told him about a drug that had demonstrated remarkable results in even the most trenchant cases, a drug that might offer hope even for him. This relatively new world-beater was an antipsychotic from Eli Lilly and Company called Zyprexa.

Since its introduction to the market in 1996, Zyprexa—often touted as a kind of miracle drug in the treatment of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder—has generated tens of billions of dollars in revenue for Lilly, more than any other drug in the Indianapolis-based pharmaceutical giant’s nearly 150-year history. To date, Zyprexa has been approved in more than 80 countries, and doctors have written more than 73 million prescriptions for nearly 24 million patients. Psychiatrists and advocates for the mentally ill widely agree that Zyprexa has helped improve the lives of most who take it.

But Zyprexa’s success has been marred by evidence that it causes serious health problems and continuing claims that Lilly downplayed that evidence while trumping up the drug’s benefits. Since 2005, Lilly has paid more than $1 billion to settle more than 26,000 product-liability claims, conflicts that cost the company significantly in both legal expenses and poor publicity. In March, Lilly settled a case with the state of Alaska for $15 million; the state argued that the drugmaker had knowingly understated Zyprexa’s potential diabetes-related complications, costing the state millions in Medicaid payouts. Lilly still faces similar litigation brought by other states.

How did this, the most important product of Indianapolis’s most important corporate citizen, come to such a vexing moment? And what is the future of Zyprexa?

The new U.S. Supreme Court session beginning this month may provide some answers. In November, the high court is scheduled to hear arguments in Wyeth v. Levine, in which the plaintiff, a drugmaker, contends that the U.S. Food and Drug Administration has sole jurisdiction in determining the effectiveness and safety of a drug. “The Supreme Court’s decision will determine whether those who are harmed by prescription drugs—drugs approved by the FDA—will be able to bring lawsuits in state courts for damage recovery,” says Marsha Cohen, an expert in food and drug law at the University of California. A ruling in the drugmaker’s favor, observers say, would free Big Pharma from many of the liability and litigation headaches that controversial medications can cause. “Basically, such a ruling would be like the Holy Grail for drug companies,” says Cohen.

But not even a Supreme Court ruling that benefits drug companies will relieve all of Lilly’s Zyprexa pains. Last month, a federal judge in New York granted class-action status to a group of third-party medical payers—including insurance companies, pension funds, and labor unions—who allege that Lilly fraudulently marketed Zyprexa, pushed doctors to prescribe it for uses not approved by the FDA, and overpriced the drug. “There is evidence that off-label use of Zyprexa was excessive and may have been encouraged by Lilly,” wrote the judge, Jack Weinstein, adding that “evidence could be relied upon by a jury to determine that, but for Lilly’s misconduct, the launch price of Zyprexa would have been set at markedly lower levels than its major competitors.” Damage estimates from plaintiff experts in the case range from $4 billion to $7.7 billion.

With thousands of medical success stories and billions in revenue, officials at Lilly—the largest private employer in Indianapolis—are still celebrating the success of Zyprexa. But its troubled path reveals volumes about how difficult bringing even an approved medication to market can turn out to be. And judging by information brought to light in the New York class-action suit, it now seems as though Lilly made risky—and possibly illegal—decisions in pitching its top-selling drug. The mounting troubles have begun to make Zyprexa, once a favorite son of the Lilly family, look like a black sheep.

The drug we now know as Zyprexa was conceived in the early 1970s in scenic Erl Wood Manor, a Georgian country estate in Windlesham, England, on the outskirts of London. In 1974, Jiban Chakrabarti, a researcher there, attended a conference in Prague on the chemical structure of clozapine, later marketed under the brand name Clozaril. The new chemical compound targeted the brain’s dopamine and serotonin receptors, which largely control normal psychological function. The drug emerged as a potentially effective treatment for psychotic disorders, particularly schizophrenia.

Although the 20th century brought the introduction of the word “schizophrenia” (a combination of the Greek roots schizo, or split, and phrene, meaning mind), the treatments it ushered in were hardly more effective—or less brutal—than their earlier counterparts, which over previous centuries had ranged from exorcism to trephining, the drilling of holes into the skulls of the afflicted. Lobotomy and electroshock therapy were among the more prominent “cures” in the first half of the 20th century Antipsychotic medications that emerged in the 1950s were notorious for their side effects, which can include muscle spasms, rigidity, restlessness, and sedation. (Such side effects account, in large part, for the image of the zombie-like patient padding along the dim corridors of the mental ward, a behavior known in psychiatric circles as the “Thorazine shuffle.”)

By some estimates, one in 100 adults suffers from schizophrenia. So when clozapine was discovered in the 1960s, the mental-health community hailed it as the possible dawning of a revolution in neuropharmacology. The first in a new class of “atypical” antipsychotic drugs, clozapine seemed to be more effective than previous drugs and, by comparison, free of side effects.

“People didn’t think there was much money in a drug for schizophrenia,” says one Lilly executive, “because they didn’t think there were that many people with schizophrenia.”

By the time Chakrabarti attended the Prague conference, however, clozapine had been linked to the occasional onset of a rare but deadly blood disease and was not widely available. Still, Chakrabarti was convinced that more research might preserve the drug’s usefulness. “I had a sixth sense,” he said years later in a historical account produced by the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA), “a feeling that something was missing in the molecular structure they had described, something that could yield a safer, better drug.”

At the time, Lilly did not have much experience in researching disorders of the central nervous system. Throughout the history of the company—founded in Indianapolis in 1876 by Civil War veteran Colonel Eli Lilly, who had been frustrated by the inadequacy of drugs available on the battlefield—research had primarily centered on infectious disease and internal medicine. Until the latter decades of the 20th century, the company’s most notable innovations included the first commercially available form of insulin, in 1923, and the mass production of several antibiotics. Those successes laid the foundation for the 40,000-plus employees and $18 billion in sales in more than 140 countries the company has today.

When Chakrabarti assembled a team at the Erl Wood facility, research on the central nervous system hovered on the periphery of Lilly’s global operations. “In those days, Lilly was a different beast than it is now,” says David Tupper, a research scientist at the Erl Wood facility and one of Chakrabarti’s earliest team members. “There was a lot more opportunity for people to do things on the side.”

By 1976, working with fellow researchers Tupper and Terry Hotten, Chakrabarti had developed an experimental molecule that was based on the structure of clozapine but modified to avoid the drug’s potentially deadly side effects. A series of stops and starts ensued: The new compound failed toxicology tests that year, as did a second version, tested in 1982. At one point, recalls Tupper, he and some fellow researchers received an urgent phone call while unwinding at a nearby pub: They would have to return to Erl Wood immediately, he was told, because an explosion had “blown up” the lab in their absence.

Despite the setbacks, by the 1980s Tupper and Hotten produced five more variations of the clozapine molecule—likely the researchers’ last shot at turning the project around before management finally pulled the plug. “If we hadn’t had those compounds made, it’s probably unlikely we would have been allowed to go back in the lab and start it up again,” Tupper says.

One of those samples was a compound researchers would later call olanzapine—the drug now known as Zyprexa. But olanzapine wouldn’t be ready for human testing until 1986, and soon, the milestone would be greatly overshadowed by the emergence of another psychotropic drug from Lilly’s laboratories—a star.

The FDA approved Lilly’s application for fluoxetine hydrochloride, or Prozac, in 1987. Before then, available treatments for depression consisted mainly of psychotherapy, electroshock, and an older generation of drugs with myriad side effects. Prozac quickly redefined depression as something that could be as easy to cure as constipation. And it became, in the process, the kind of product every company dreams about: a brand that creates an industry and becomes synonymous with it in the minds of the buying public. Kleenex to facial tissue. Coke to soda pop. Pampers to disposable diapers. Prozac was a cultural phenomenon, the subject of books and the punch line of late-night talk-show hosts. In the words of one Lilly official, it was a “metaphor for psych meds.”

In 1988, Prozac’s first year on the market, the drug brought in more than $100 million and became one of the company’s most successful launches. In November 1987, a month before Lilly’s Prozac application was approved by the FDA, the company’s stock was trading at under $67 per share; by 1989 it was trading at well more than $100 per share. By 1994, Prozac had surpassed $1 billion in annual sales, and, largely on the coattails of the Prozac phenomenon, Lilly—once a middle-of-the-pack drugmaker known for less-sexy medications such as insulin and antibiotics—was building a reputation as a pharmaceutical-industry heavyweight and Wall Street darling.

Perhaps more important, the ubiquitous antidepressant ushered in a new era in Lilly’s approach to drug development. “Prozac allowed us to create capability in psychiatry that we didn’t have previously,” says Bob Postlethwait, former president of Lilly’s Neuroscience Product Group. “Worldwide, Lilly took on an image of being the company that was most focused on central nervous system disorders. So recruiting of top scientists emerged, recruiting of investigators to work on things that Lilly had, and we reached a critical mass.”

Lilly’s stock split in 1989, after trading at more than $100 per share, and by 1991 had climbed to more than $80 per share. Prozac’s annual sales continued to grow, but it was nearing full maturity.

Fortunately, olanzapine was still making its way through the pipeline. “We became pretty excited about the therapeutic impact and also the commercial opportunity of the molecule olanzapine,” says Postlethwait. The main impetus in turning attention to olanzapine, Postlethwait insists, was a “very keen awareness of the clinical deficit of current therapies that were out there.” But, he adds, “there’s no doubt about it—there was a pragmatic intent there for investors.”

New Lilly CEO Randall Tobias arrived in 1993 with the intention of bringing, as he was later quoted as saying, “a sense of urgency” to the company. That year, Lilly competitor Janssen, a division of behemoth Johnson & Johnson, received FDA approval for Risperdal, the brand name of its new compound, risperidone, touted as a safer alternative to clozapine. Having been beaten to the antipsychotic market, Tobias later told company shareholders that, in the development of olanzapine, “What had been a hunt was now a race.”

In September 1995, led by what Lilly termed a “heavyweight” team (designed to streamline the development process and employing what Tobias described as “a very aggressive new approach”), Lilly submitted an application to the FDA. In anticipation of approval, Lilly’s manufacturing facility in Puerto Rico began churning out the drug, hampered only slightly by a hurricane that forced the plant to operate on a backup generator.

At 6 p.m. on September 30, 1996, Zyprexa, olanzapine’s new brand name, received the green light for sale in the United States as a schizophrenia treatment. An Indianapolis pharmacy filled the first prescription at 5:30 p.m. the next day. Zyprexa set a record for shortest time elapsed between FDA approval and appearance on the market.

It wasn’t immediately apparent to analysts—nor even to much of Lilly management—that Zyprexa would quickly grow up to become a top seller. “People didn’t think there was much money in a drug for schizophrenia, because they didn’t think there were that many people with schizophrenia,” says Dr. John Hayes, a psychiatrist and vice president of Lilly Research Labs.

But Lilly’s marketing gurus didn’t leave good sales to chance. On the day after the FDA approval, Lilly held a teleconference touting its efficacy and minimal side effects. In one of the earliest signs of trouble for Zyprexa, however, the FDA issued Lilly a warning almost immediately after the teleconference, stating that Lilly promotional materials implied that Zyprexa was superior to other antipsychotic medications—a claim that could not be substantiated. “The promotional materials emphasize efficacy data,” the warning read, “but do not provide sufficient balance relating to adverse events and cautionary information.”

Nevertheless, in 1997, its first full year on the market, Zyprexa generated nearly $750 million in sales—a figure that exceeded Prozac’s first-year sales sevenfold. Pressure on Lilly’s Prozac patent was increasing—and would, with the introduction of generics, eventually cut the depression drug’s sales by more than two-thirds—but Zyprexa was calming revenue anxieties.

Zyprexa crossed the $1 billion-per-year threshold in three years, compared to Prozac’s five. In 1999, its sales approached $2 billion—up 45 percent from the previous year—and Lilly’s company profits, driven by Zyprexa’s runaway success, were up 16 percent from the previous year.

“You ask, ‘How is Zyprexa such a big seller?’” says Hayes. “It’s really good. You can fool some of the people some of the time, but you can’t fool all the people all of the time. Drugs that don’t really help people don’t have huge market success.” The drug’s success was also buoyed by its cost: According to court documents, Zyprexa treatment can cost as much as $1,404 per month, 31 percent more than a comparable antipsychotic offered by a Lilly competitor.

It seems that Lilly officials, realizing they had another golden goose, reverted to the outline that had worked so well with Prozac, which came to be touted for everything from obsessive-compulsive disorder to bulimia. In 1999, Lilly sought FDA approval to market Zyprexa for the treatment of bipolar disorder, and in June 1999 Pharma Marketletter, an industry publication, reported that Lilly was investigating use of the drug in the treatment of dementia.

“The cost of getting a drug to market is estimated at more than $1.2 billion, and that includes all the cost you sunk into things that never make it,” says Hayes. But once a drug starts generating revenue, he says, the company can afford to explore other potential uses for the drug that might not have appeared during the development process. “If it’s the greatest thing since sliced bread, and then people take it, and now everybody’s on it, sales will flatten out,” says Hayes. “From a business standpoint, it makes perfect sense that, if you can, you bring another indication” to the market.

According to court documents, in 2001, at a national sales meeting, the company announced a “Viva Zyprexa” sales campaign and signaled a shift toward promoting the medication to primary-care physicians (PCPs) instead of just psychiatrists and mental-health specialists. Company literature outlining the shift, and cited in Judge Weinstein’s class-action decision, explains that “most PCPs currently prescribe a low volume of antipsychotics and mood stabilizers” because “Zyprexa’s primary indications—schizophrenia and bipolar—are not viewed as PCP-treated conditions.” Lilly suggested having its reps recommend the drug more vaguely for “mental disorders” and “frame the discussion around symptoms and behaviors rather than specific indications.”

Lilly later announced Zyprexa sales exceeding $3 billion for 2001. What’s more, for the first time, Zyprexa’s annual sales surpassed even those of Prozac. And the news couldn’t have come at a better time: In 2000, a federal appeals court had ordered the expiration of Lilly’s Prozac patent two years earlier than company officials had anticipated.

But red flags over possibly serious side effects were about to dog Zyprexa’s ascendancy. A study published in the November 1999 issue of the American Journal of Psychiatry, which compared data on numerous antipsychotics, renewed early concerns about the relationship between Zyprexa and weight gain, revealing that Zyprexa users appeared to gain an average of nearly 10 pounds in 10 weeks—second only to clozapine among the newer class of antipsychotic drugs. “Emerging data suggest that the drugs causing weight gain (i.e., clozapine and olanzapine),” the report concluded, “may, perhaps as a result, also be causing type II diabetes.”

Competitors, undeterred by public reassurances from Lilly, seized on the increasingly negative reports surrounding Zyprexa as an opportunity to take a chunk out of Lilly’s dominance. In 2001, without specifically naming Zyprexa, Janssen, maker of Risperdal, started placing print ads in psychiatric publications, showing two people and the words, “Which patient developed new-onset diabetes with his atypical antipsychotic?” Later that year, Pfizer trumpeted the results of a study in support of its new antipsychotic, Geodon, proclaiming that the drug was “significantly better tolerated in terms of weight gain … and insulin levels” in comparison to Zyprexa.

In 2002, regulators in Japan, reacting to reports of diabetes deaths allegedly linked to Zyprexa, banned its use among patients with a history of diabetes. And in the same year, researchers at the Duke University Medical Center published the results of a study of the possible Zyprexa-diabetes link in Pharmacotherapy, the journal of the American College of Clinical Pharmacy: Of the more than 200 diabetes cases among Zyprexa users that they reviewed, the researchers determined that a large majority of the diabetes cases were new-onset. More than a dozen patients had died from diabetes-related complications.

As recently as 2006, a massive federally funded drug trial of several antipsychotics, commonly known as the CATIE study, concluded that Zyprexa “was associated with substantial weight gain and metabolic problems, more so than the other medications.”

“There is something about having schizophrenia that predisposes you to metabolic disorders, to being overweight,” says Hayes. “What [the study] really told us was that all the patients who have this disorder are at high risk for weight gain and metabolic problems. We don’t understand what that risk is, but it exceeds the risk in the general population. And it’s not just due to treatment. There are very few people in the field who wouldn’t agree with me now.”

By 1987, Ellen Liversidge, frustrated by her son’s years of marginally effective psychiatric treatment, sought out a new doctor, who researched Rob’s case history and determined that he suffered not from schizophrenia—for which he had been treated with Haldol and Stelazine, old-line antipsychotics—but a related psychosis, bipolar disorder. Rob began taking lithium—a drug prescribed to moderate the extreme highs and lows associated with the illness—and the change precipitated a turning point. After the painful false starts at Cornell, Rob, with a seemingly correct diagnosis and lithium regimen, enrolled at Temple University and finished his undergraduate degree, and then returned to Cornell and earned a master’s degree in city and regional planning in the mid-1990s. He had a steady, long-term girlfriend and submitted applications to doctoral programs at Harvard and MIT.

From his mother’s perspective, Rob’s life seemed to be back on track. But by 2001, his doctoral applications had been rejected, his girlfriend had left him, and he was having trouble finding work. “When Rob was in grad school, there was structure,” says Ellen. “But when he got out into the world, it was harder for him to get it together. He was just wobbly in life. Rob’s episodes were always triggered by some kind of crisis.”

As these latest setbacks mounted, Rob sometimes grew paranoid and started worrying that the government was after him. He was afraid he might do harmful things to himself. At a hospital in Maryland, where he and his mother now lived, a new psychiatrist told Rob he needed “something stronger” than the lithium he had been taking for more than a decade. That “something stronger” was Zyprexa, which had been approved by the FDA for the treatment of bipolar disorder the year before.

For Rob, the drug did prevent further moments of severe psychosis from surfacing. But the relief, says Ellen, came at a price. “He would spend the entire day in bed,” she says. “Sure, he didn’t have any episodes, but he did absolutely nothing. His life had no quality to it.” She says that Rob, who stood 5-foot-10 and weighed about 200 pounds when he started taking the medication, gained an additional 100 pounds in the span of just over a year. And on one trip to the doctor, she says, a blood test showed that he was starting to show signs of hyperglycemia, or elevated blood-sugar levels, a precursor to diabetes.

On a Sunday in September 2002, a little less than two years after he started taking Zyprexa, Rob complained to his mother that he felt “weird.” He considered going to a hospital, but he didn’t. Two days later, he felt worse, and Ellen recalls that a sudden look of terror crossed his face. Rob called out to his mother. “I still remember the last words he spoke,” she says. “He cried out my name.” Moments later, Rob was unconscious.

When Rob and Ellen arrived at the hospital, she says, doctors informed her that her son had fallen into a diabetic coma. They were utterly puzzled, she says, by what might have induced Rob’s sudden and precipitous rise in blood sugar, and even tried testing him for HIV and West Nile virus. “They had no idea what had caused it,” says Ellen.

He never woke up. Four days after he was admitted to the hospital. Rob Liversidge, 39, was dead.

As more and more reports of cases like Rob Liversidge’s reached the public (Ellen Liversidge was, in fact, one of the first alleged victims to go public when she told her story to a Baltimore Sun reporter in 2003), it was only a matter of time before personal-injury lawyers got involved. In February 2003, Hersh & Hersh, a firm in San Francisco, filed suits on behalf of several plaintiffs, alleging they or family members had taken Zyprexa and, unaware of the risk of diabetes, sustained fatal or near-fatal illnesses.

Hayes suggests that bad outcomes tied to Zyprexa often owe more to how the medication is administered than the drug itself. “It takes a whole community of help around—the family, the friends, the doctors,” says Hayes. “Zyprexa is a piece of that. When it is used in that way, people have remarkable recoveries. When it is used as Just take this and come back and see me in six months, the results aren’t as good. That’s true of almost any drug. And unfortunately, it’s what happens a lot in medicine today.”

Ellen Liversidge contacted Hersh & Hersh, and in 2003 she joined a group of patients and families—a group that would swell to include thousands of people over the course of the following two years—in seeking consolation through litigation.

A few months after Hersh began filing claims, the FDA requested that Lilly include a diabetes-related warning on Zyprexa. (The makers of several other antipsychotics received similar requests.) In 2005, Lilly settled more than 8,000 product-liability suits for close to $700 million—a staggering sum, to be sure, but Zyprexa had already grossed tens of billions of dollars. It would generate $4.2 billion in sales in 2005 alone.

News of the 2005 settlement, says one attorney, “lent some validity to our understanding that Lilly did something wrong here.”

Ellen won’t discuss the amount she received from the settlement, though the total sum spread among 8,000 plaintiffs amounts to about $86,000 per claim—before attorney fees. “I gave it to my daughter to pay off student loans,” she says.

In 2005, Ed Sniffen, an assistant attorney general in Alaska who specializes in consumer protection, started getting phone calls from state legislators. They were reading the news. And they wanted to know whether the state might have a viable claim against the maker of Zyprexa.

Sniffen had already started his own investigation. Early on, he says, he came across a letter Lilly had mailed to physicians in 2005. “It basically explained that the warning label on the drug Zyprexa may not have been adequate, and doctors should take extra precautions when prescribing the drug, and be aware of these particular side effects,” says Sniffen.

Between 2002 and 2006, Alaska physicians prescribed Zyprexa to approximately 6,000 Medicaid patients, at a cost of more than $1 million to the state’s healthcare program. News of Lilly’s massive 2005 Zyprexa settlement, says Sniffen, “lent some validity to our understanding that Lilly did something wrong here.”

In March 2006, Sniffen, on behalf of the state of Alaska, filed a complaint in an Anchorage court that alleged “Lilly well knew, when it instructed its drug representatives to make fraudulent misrepresentations to Alaska physicians, that the state was by far the largest purchaser of Zyprexa, as well as the purchaser of much of the medical care that would be required by patients who developed diabetes after using Zyprexa.” Alaska became one of 12 states—including Arkansas, Connecticut, Idaho, Louisiana, Mississippi, Montana, New Mexico, Pennsylvania, South Carolina, Utah, and West Virginia—that have filed similar claims alleging that Lilly was liable for costs that state healthcare programs would incur in treating Zyprexa-related diabetes complications. (Lilly’s home state of Indiana has not.)

Alaska’s would become the first—and, at present, only—such case to go to trial. Lilly called in the high-powered Philadelphia firm of Pepper Hamilton. (Lilly’s legal team, according to several reports, claimed an entire floor of an Anchorage hotel.) For its part, the Alaska attorney general’s office employed the services of several trial specialists. But, according to Scott Allen, a Houston-area trial lawyer brought in by Alaska, “They had us outmanned, outgunned, and outspent. They had an array of legal talent and a huge staff. They had the money and the power.”

And if the proceedings promised drama, they did not disappoint. Testifying for the plaintiff, former FDA medical reviewer and diabetes expert Dr. John Gueriguian criticized Lilly for failing to warn of known diabetes risks associated with Zyprexa and accused the company of “putting profit over the concern of the consumer.” Lawyers for Alaska also tried to raise the issue of Lilly’s alleged off-label promotion of Zyprexa, a commonly waged charge that has come to cloud marketing efforts surrounding the drug. They presented an e-mail message written in 2003 by now-CEO John Lechleiter to other company executives, in which he wrote, according to a report in The New York Times: “The fact we are now talking to child pychs and peds and others about [Lilly ADHD drug] Strattera means that we must seize the opportunity to expand our work with Zyprexa in this same child-adolescent population.” (The FDA has not approved Zyprexa for use among children or adolescents.) The presiding judge declined to allow Alaska to raise the issue of off-label promotion, and Lilly, in a company statement, retorted that the Times had “mischaracterized” Lechleiter’s e-mail.

A few days into the trial, however, Alaska’s attorney general accepted a $15 million settlement offer. The decision disappointed Alaska’s outside lawyers, who say they were not consulted about the agreement. “It came out of the blue,” says Allen. “Had I been asked about it, I would have advised them to say, ‘No.’ We were going to win that case, and it was going to be substantial.”

Although Lilly might have put the Alaska matter behind it, at press time the company still faced the prospect of paying billions of dollars to settle pending Zyprexa litigation brought by 11 other states. And while Lilly officials won’t comment on the possible implications of the Supreme Court’s decision on Wyeth v. Levine, many observers anticipate a ruling in the pharmaceutical industry’s favor—and at least a partially comforting salve for Lilly’s Zyprexa-inflicted wounds.

But a favorable Supreme Court ruling is not likely to spell the end of Lilly’s troubles with Zyprexa. Some pharmaceutical-industry critics argue that Lilly executives should face criminal charges for the company’s allegedly fraudulent marketing of Zyprexa and its downplaying of the drug’s side effects, (And at press time, the U.S. attorney’s office in Philadelphia had an open investigation into such charges.)

“Our impression of Eli Lilly is that white-collar criminals are in charge,” says David Oaks, executive director of the mental-illness advocacy group MindFreedom International. “The cover-up about diabetes [associated with Zyprexa]. Not coming clean about their early knowledge of diabetes. I’m not a lawyer, but if these things aren’t criminal, they should be.” Of course, Lilly officials dismiss such charges. “I believe if you really research anything we’ve done, you’ll find some errors, either real errors or errors in judgment, that people make along the way,” says Hayes. “In the biography of any drug, I think you’ll encounter some error. I think you’d be hard-pressed to find any outright, prospectively, organized, nefarious behavior. And if you do find some—you, me, anybody—I suspect it happens in isolated pockets. I’m sure it would be possible to find a salesperson who said something inappropriate.”

Whether or not criminal charges ever come to bear on Lilly, its chances of emerging from the class-action suit in New York without paying substantial damages appear increasingly slim. In his nearly 300-page decision granting class-action status to the third-party medical payers who have sued the company, Judge Weinstein gets to the heart of a question that has perplexed more than one observer of Zyprexa’s astounding profitability: How did a drug designed for schizophrenia—a common though not pervasive mental disorder—become the top-grossing drug in Lilly’s history and one of the best-selling drugs on the market?

“It is alleged that over the twelve-year period since Zyprexa’s introduction in 1996 to today, Lilly has withheld information and disseminated misinformation about the safety and efficacy of Zyprexa and has promoted and marketed the drug for uses for which it was not indicated and for patients who would have been better served by less expensive medications,” writes Weinstein. And further statements leave little doubt as to his view of at least one of Lilly’s alleged missteps. “Lilly’s marketing efforts succeeded in greatly increasing the number of off-label sales of the drug,” he states. “Without off-label marketing, Zyprexa—originally approved for the treatment of conditions affecting less than one percent of the population—could not have become the seventh best-selling drug in the world.”

Perhaps the only question that remains, then, is not how much money Lilly will have made from its No. 1 drug when all the legal dust finally settles—but how much money the drug, in the end, will have cost.