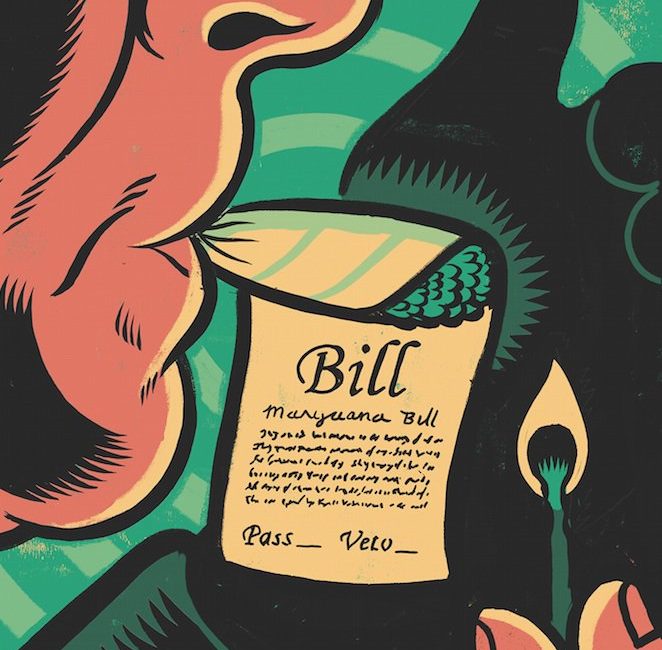

Is Indiana On The Verge Of Legalizing Medical Marijuana?

In the fall of 2015, the Indiana Senate Agriculture and Natural Resources committee gathered at the Statehouse for yet another study on the potential legalization of cannabidiol oil, or CBD oil, for children with intractable epilepsy. In the back of the room, waiting to testify in support, were the head of the Epilepsy Foundation of Indiana, multiple doctors, and the parents of kids who had found relief from seizures by illegally using CBD oil, an extract derived from the cannabis plant that has no psychoactive properties—it doesn’t get users high.

Striding to the podium in opposition, Aaron Negangard, the Dearborn County prosecutor at the time, wore a charcoal-gray suit with an American flag pin prominent on his left lapel. His hardline stance on drugs had attracted the attention of The New York Times in 2016. (“If you’re not prosecuting, you’re de facto legalizing it,” he said.) Negangard was officially there to represent his district, but he also stood as a kind of proxy for the Indiana Prosecuting Attorneys Council (IPAC)—the lone opposition standing in the way of CBD legalization. It was his job, after two hours of testimony, to rest the prosecution’s case, so to speak. It was pretty open-and-shut, as far as he saw it: Not only were the cannabis plant and all its derivatives Schedule I drugs, and thus a federal crime to possess, but there hadn’t been enough scientific research done to warrant CBD oil’s legalization, even for kids whose seizures had resisted all other legal options.

“We have anecdotal evidence, at best,” Negangard said.

What seemed to worry IPAC the most, however, wasn’t the potential harm of putting an unregulated drug in the hands of desperate parents, as much as it was concern over what legalizing CBD oil might lead to. “What we need to be careful of,” Negangard told the legislators, placing both hands firmly on the podium, “is opening the door to decriminalizing marijuana.” The way the prosecutors saw it, legalizing CBD oil would inevitably lead to the legalization of another cannabis-derived substance with purported medical benefits: tetrahydrocannabinol (THC)—the stuff that gets users high. And that, well, there was no telling what might happen if that were to occur.

It proved to be a winning argument—when Republican Senator Jim Tomes introduced a bill to legalize the substance for epileptic patients the following legislative session, it died a quick death in an unfavorable committee. CBD oil supporters were devastated, but they learned from the experience. In subsequent years, armed with new studies showing other health benefits of the oil and emboldened by rising public support, they refined their approach and focused on educating lawmakers. It finally worked. This past March, the legislature passed SB52, legalizing CBD oil for all Hoosiers, a bill that Governor Eric Holcomb signed into law.

The Indianapolis Star and other outlets covered the entire saga, but a piece of related legislation passed with far less media attention. In some ways, it’s a direct result of the efforts on the CBD oil front. Without a single dissenting vote, the House also approved HR-2, calling for a study committee to look into something that would have seemed inconceivable a few years ago: legalizing medical marijuana.

In the early 20th century, Eli Lilly and Company produced and sold medical marijuana in several forms to treat a variety of ailments, most prominently as an analgesic (non-addictive painkiller), a sedative (sleeping aid), or an antispasmodic (muscle relaxant). Prior to World War I, almost all the cannabis Lilly used—in products like Dr. Brown’s Sedative Tablets, for instance—was shipped from India, a strain known as Cannabis Indica. But when importing raw material grew to be a dicey proposition during the war, it became imperative for pharmaceutical companies to grow the product in-house, which Lilly did at its farm in Greenfield, Indiana.

And man, did they come up with some killer stuff—Cannabis Americana was the first domestic strain to rival the Indian import in both potency and medicinal effectiveness. But by the 1930s, the political climate had changed. Harry Anslinger, the head of the Federal Bureau of Narcotics and the man known as the architect of America’s War on Drugs, used race-baiting and fear-mongering to demonize cannabis. (“There are 100,000 total marijuana smokers in the U.S.,” Anslinger said, “and most are Negroes, Hispanics, Filipinos, and entertainers.”) His efforts eventually led Congress to pass the 1937 Marijuana Tax Act, which placed heavy regulatory requirements on the production and sale of cannabis, effectively criminalizing the plant federally and halting all medicinal use in the United States for decades.

Here in historically conservative Indiana, the state legislature was one of the first to ban the use of cannabis without a prescription. Before long, Indiana had some of the strictest marijuana laws in the country, and it remains one of only 17 states that has yet to legalize the drug in some fashion, with simple possession drawing up to 180 days in jail and a $1,000 fine. In 2013, then-Governor Mike Pence shot down a bill that had passed through the House and would have decriminalized small amounts of marijuana, telling reporters, “I think we need to focus on reducing crime, not reducing penalties.”

After 75 years of zero tolerance, along came CBD oil, bringing the issue back to the forefront and forcing legislators to answer a question that had, at one time, been decided here: Is cannabis capable of offering medical benefits?

It took nearly four years for an answer to emerge, with supporters fending off public opposition from Attorney General Curtis Hill. In 2017, after the passage of a bill establishing a CBD registry prompted raids by excise police and the arrest of confused citizens, Hill publicly weighed in on the issue, declaring that CBD oil, because it came from the cannabis plant, which was illegal at the federal level, was thus illegal in Indiana.

The resulting public outcry caused Governor Holcomb to issue a moratorium and demand that the legislature find a solution during the ensuing session, which they did, overwhelmingly. Of the 144 members of the General Assembly who voted on SB52, only 11 remained, as one lawmaker put it, “sympathetic to the prosecutor’s case.” But as IPAC attorney Negangard feared, it didn’t stop there. With an increasing number of Hoosiers in favor of dismantling more marijuana laws and a study of the curative properties of cannabis underway this summer, CBD oil may be just the beginning.

So what does the passage of the CBD oil bill mean for the future of medical marijuana in Indiana? It depends on whom you ask.

“You’re going to be shocked,” says David Phipps, the communications director for the Indiana chapter of the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws, when asked for a prediction. “I think we have a realistic chance, as long as we do a good job with the summer study, educating our legislators on the truth behind this. I think we can get it as early as the next General Assembly.”

While that may seem optimistic—after all, it took Indiana more than 80 years to fully repeal alcohol prohibition—it’s not totally unreasonable, considering the momentum behind the movement. In a statewide poll conducted in 2016 by WTHR/HPI, 73 percent of the 600 Hoosiers surveyed supported medical marijuana.

Advocates say that if the question were posed today, the number would be even higher, approaching 80 percent. That’s how high support is among veterans, according to the American Legion, who joined the fight in 2016 after their members demanded it, and who have been increasingly active at the Statehouse, advocating for permission to explore the potential of medical marijuana in treating vets with PTSD and opioid addiction.

“It’s immoral that the state still has this criminalized,” says state representative Jim Lucas. “Lives are being destroyed by the opioid crisis. It’s gotten to the point where it’s forcing us to look at the War on Drugs in a bigger context.”

Lucas and others are quick to point out that 29 states have legalized medical marijuana—including Ohio, Illinois, and Michigan—where opioid deaths have decreased by an average of 25 percent. Marijuana isn’t a “gateway” drug, in other words, say supporters—it’s a potential “off-ramp” for those suffering from the ravages of opioid addiction.

It’s a strong argument, one that resonates across political and class lines. “We would welcome that drug problem,” says Dillo Bush, the mayor of Austin, Indiana, ground zero for the state’s HIV outbreak, a direct result of the opioid epidemic. Bush is a retired union pipe-fitter, a blue-collar Southern Indiana Democrat, and he’s no fan of marijuana. He doesn’t understand why people put any drugs in their systems. But if it can help curb the opioid problem that has decimated his city, he’s all for it.

The opposition doesn’t see it from the same perspective. Hill has opined multiple times on the issue, most notably last summer in an Indianapolis Star op-ed, in which he wrote: “Legalizing a gateway drug such as marijuana leads vulnerable people to worse substances such as methamphetamine and heroin.” IPAC also has been vocal in its opposition, stating that “information purporting that marijuana is medicine is based on half-truths and anecdotal evidence.”

Even Governor Holcomb, who praised the legislature for delivering “exactly the bill I asked for” regarding CBD oil, isn’t ready to see the state go further. “At this time, I’m trying to get drugs off the street, not add more into the mix,” Holcomb said in November, when asked about the possibility of passing medical marijuana. “I would say to those folks seeking to decriminalize or to legalize marijuana for medical or other uses, that they need to be talking to the FDA first.”

It’s not just outside parties that proponents will need to convince, either. Inside the Statehouse, particularly in the Senate, enthusiasm is tepid for legalizing medical marijuana. Senator Tomes, who readily acknowledges that cannabis is “God’s plant,” and is a big believer in the benefits of CBD oil, worries about abuse and is currently against legalization.

A lot more will be known later this summer when members of the study committee gather once again to hear testimony on the subject. As unlikely as legalizing medical marijuana here seems, it’s in the same position CBD oil was in back in 2015. Advocates hope for second hit.

Read our March 2019

Marijuana feature here.