Troubled Waters

Some endangered animals naturally tug at our hearts—the sleek Florida panther, or the majestic blue whale. There’s even a term scientists use for those types of high-profile species: “charismatic megafauna.” But a battle is brewing just north of Indianapolis over a species that has less luck inspiring that level of affection.

Freshwater mussels are considered the most imperiled group of animals on earth, attributable to over-harvesting, water pollution, and habitat loss. Of the world’s 800-plus species, the United States is home to nearly 300—more than 35 percent of the global population. They are unique in their ability to actually clean the water they dwell in, and their presence is a sign of a high-quality environment. A freshwater mussel has the capability to filter up to a gallon of water per hour, a trait that makes it sensitive to many types of pollution. Nearly 50 different species are native to the Tippecanoe River. Six have been classified by the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service as federally threatened or endangered due to declining populations nationwide.

Dry conditions plaguing the state over the past few years haven’t helped. A drop in water levels caused by an extreme drought in 2012, for instance, led to a high mortality rate for the listed mussels in an 18-mile stretch of the river that flows below the Oakdale Dam to its confluence with the Wabash. A second die-off was observed in September 2013. Though the animals do have some mobility, their power to escape rapidly falling water levels is limited. To keep the mussels thriving, the FWS wants to implement a plan that has sparked debate in the waterfront communities in White and Carroll counties.

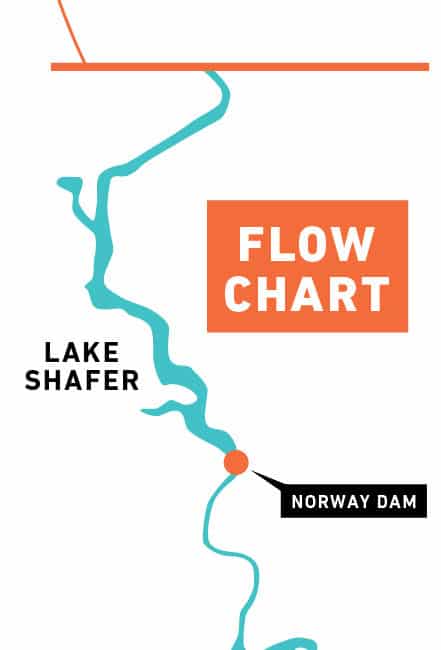

Lake Freeman, created by the Oakdale Dam, and Lake Shafer, its smaller sister to the north formed by the construction of Norway Dam, were built in the mid-1920s to generate hydroelectric power. They were not designed for flood control. But now the FWS has mandated that the dam owner and operator, utility Northern Indiana Public Service Company, maintain a minimum flow rate through Oakdale and into the Tippecanoe to ensure the mussels’ survival. To do this, the waters of Lake Freeman may need to be lowered periodically during prolonged dry periods in the watershed. Therein lies a problem.

Since their creation, the two impoundments, widely known as the “Twin Lakes,” have witnessed huge growth, much of their development stemming from the founding of Indiana Beach, the state’s largest and oldest continuously running amusement park. Year-round residential and vacation homes now line both lakes. Numerous businesses rely on the nearly 1 million visitors who spend time and money in Monticello and surrounding communities. The area is one of the largest generators of tourist dollars in Indiana. Much of that development and infrastructure depends on stable year-round lake levels. A drawdown could result in income losses for tourism-dependent businesses and inaccessibility to lakefront property, and jeopardize native fish and wildlife, including non-endangered mussels.

But hold on—there’s more. The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, the agency responsible for allowing any changes to the utilities’ dam-operating license, released a draft report that seemed to concur with the environmental corporation’s opinion, placing it squarely at odds with the Fish & Wildlife Service’s position. Citing studies prepared by a professional hydrologist hired by local parties, and their own researchers and biologists, FERC appears to side with the lakes group regarding the distance of the Winamac gauge, and even questions the principles of linear scaling itself.

The energy commission is now in the process of completing its final report on the Fish & Wildlife Service request to amend the Oakdale operating license—which currently allows a water-level fluctuation of only three inches above to three inches below a stable elevation of 612 feet over sea level. They hope to have it completed by the end of the year. Even if their final report continues to support the long-established operation of the Oakdale Dam to maintain a stable lake level, it may be overruled. As a FERC representative mentioned during one of its local public meetings, the Fish & Wildlife Service, operating under the legal mandate of the powerful Endangered Species Act, will have the last word on the outcome of this dispute.

For now, a temporary stalemate exists between the two federal agencies. And the people of the area, stuck in an uneasy middle, hope a healthy amount of rain continues to arrive. Meanwhile, the mussels hang on in the peaceful waters of the Tippecanoe, as they have for thousands of years, oblivious to all the turmoil that surrounds them.

Jerry Sweeten, professor of biology and director of environmental studies at Manchester University, holds a federally endangered northern riffleshell mussel from the Tippecanoe River in White County. The green glitter helps distinguish male from female mussels.

Several species of mussels are endangered, in part because of over-harvesting. Some prize the mollusk’s shells and pearls.

A female plain pocketbook mussel displays her “lure,” hoping to attract a potential host fish to assist in the reproductive process. If a curious fish comes close enough, the mussel will release fertilized eggs. These parasitic larvae, called glochidia, attach to the gills of the fish until they are mature enough to abandon the host and survive on their own.

A freshwater mussel rests on the streambed of the Tippecanoe. Nearly 50 species make their homes here.

Though the bivalves do have some mobility, their power to escape rapidly falling water levels is limited. Mussels must have enough water to cover them to live.

A lone fly fisherman casts into the frothy tailwaters of the Oakdale Dam seeking species such as smallmouth bass, hybrid striped bass, and walleye. Four state-record fish have been caught in these waters along the Tippecanoe and on lakes Freeman and Shafer, and anglers come from all over the Midwest to try their luck.

Boating and paddling are also popular activities.

Nearby establishments, like the Oakdale Inn Restaurant, do booming business.

Audience members listen to speakers during a public meeting last May between federal agencies and lake-area stakeholders.

Numerous recreation-related businesses rely on the nearly 1 million visitors who spend time and money in Monticello and surrounding communities.

The Madam Carroll excursion boat arrives at its homeport on Lake Freeman. The largest such craft licensed in the state, it would actually be classified as a ship on anything other than inland waters. The 135-foot-long and 36-foot-wide steel-hulled vessel can carry up to 500 passengers and has navigated Freeman’s waters since 1976.

Sharon Miller walks along the seawall that protects her Lake Freeman property. Miller bought her lakefront home as a weekend retreat, then permanently relocated from Indianapolis to Monticello in 1983. She had the steel seawall built in the mid-1970s to help control bank erosion, a common problem on the steep-sided lake. Pondering the uncertainty facing the future of her lake, Miller asks, “Does anyone really know what they are doing?”

When river levels are low, the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service uses a gauge at Winamac to determine the minimum amount of water that must flow from the Oakdale Dam using a methodology called linear scaling. The questions surrounding the procedure and the location of the gauge, 45 miles upstream of the dam, is a major point of contention between the FWS and the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, which is responsible for the licensing the operation of the dam.

Dr. Sweeten pounds a marking stake into the Tippecanoe during a northern riffleshell mussel-augmentation program in White County.

Water level is crucial to freshwater mussel surival.

Laura Esman, a Natural Resources Social Science Lab research associate for Purdue University, installs a sign at the public-access site on the Tippecanoe River below the Oakdale Dam. Part of a public-education and outreach program emphasizing the value and protection of freshwater mussels, the sign was funded by a grant from the Indiana Department of Natural Resources.

Freshwater mussels are considered the most imperiled group of animals on earth, attributable to causes including over-harvesting, water pollution, river damming, and sedimentation.

Brant Fisher (green cap), a non-game aquatic biologist from the IDNR, and FWS biologist Elizabeth McCloskey (pink cap) lead a group of volunteers as they carefully place male and female northern riffleshells in a specific grid, hoping to enhance the mussels’ chance of reproduction.