Phil Gulley: Moral History

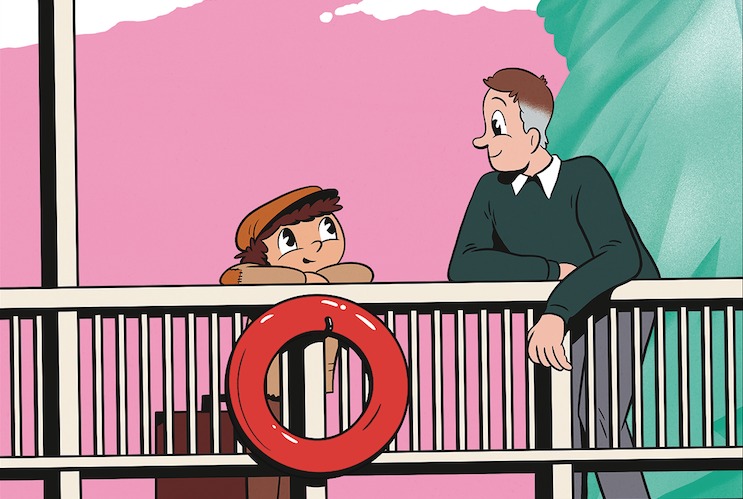

With all of our talk about immigration these days, I’ve been thinking about my grandfather a great deal, Grandpa Hank being the immigrant I knew best. He’s gone now, but his certificate of citizenship hangs in my garage, directly above another native from the old country, my 1974 Triumph Bonneville motorcycle. Grandpa arrived on a boat from Belgium at the age of 5 in 1909 and became a U.S. citizen in 1938. I’m not sure why it took 29 years for him to gain citizenship, other than the fact that he was deliberate about everything he ever did, so he probably wanted to make sure he was going to stay before bothering with paperwork. On the certificate, he signed his name Henry Quinet, with only one “t”, even though an official at Ellis Island had spelled it Quinett to make it seem more American. Grandpa was proud of his Belgian heritage, and in his mind he was a Quinet no matter what the government said.

Grandpa was a disciple of routine. He began each day of his retirement sweeping the sidewalk and gutter in front of his house on 5th Street in Vincennes. He ended each day sitting in his rocker watching Walter Cronkite, except on Saturdays, when he watched Lawrence Welk. Every Sunday evening, his younger brother Octave would come to his house and they would play euchre—two old men in ratty cardigans, bickering in Walloon, the dialect of their native Belgium.

Though he traversed an ocean and half a country to get to Vincennes, once he arrived, he wanted nothing to do with travel. The farthest he ever strayed from Vincennes was to Fence Lake in Wisconsin for a family vacation. He was miserable the whole time, and as is customary of miserable people everywhere, he made sure everyone was aware of it.

Despite his regular forays into misery, I looked forward to our visits to Vincennes, when Grandpa and I would retreat to his workshop and make stools, birdhouses, or whatever struck our fancy. His workshop contained electric tools cobbled together from discarded equipment others had thrown away. I can’t count the times I was shocked by an improperly wired drill or saw. He acquired his lumber from piles of debris at building sites or broken-down furniture from the curb. My bedside table is made of cherry and walnut he scavenged from a cupboard a neighbor had set out for the trash collector.

He came to woodworking early in life, when his father pulled him from school at the age of 13 to work in a glass-cutting factory hammering together pallets. Grown men were away fighting World War I, jobs at the factory went unfilled, and my great-grandfather decided a sixth-grade education was sufficient for his oldest son, so Grandpa went to work, 12 hours a day, six days a week. For the next 10 years, he gave every paycheck to his parents, keeping his last one when he married my grandmother in 1927.

They were married at 7:30 in the morning at my grandfather’s insistence, so they could drive all day to visit my grandmother’s family in West Virginia. Two years later, they purchased a home in Vincennes for the princely sum of $1,600. A month after that, the stock market crashed, ushering in the Great Depression. For the rest of his life, he began every conversation with the words, “Why, when I was young, we had nothing. No one had anything. We were all broke.” That wasn’t entirely true. Window glass remained in demand, so Grandpa kept his job until the age of 62, when the factory shut down in 1966. The pension fund had been drained by the owner, so Grandpa went to work selling school equipment across Southern Indiana, then quit that job to work for an architect. If you ever visited the library at the Old Cathedral in Vincennes, you were standing in a building designed by a man with a sixth-grade education.

I never knew his parents, my great-grandparents. My mother said they were warm and loving, but when my grandfather was a boy, his father denied him an education and his mother threw an ax at him, striking him in the arm. I can’t imagine why parents would do that to their children, and it bothers me that their DNA comprises part of my genetic essence. I look for signs that I might be like them, a fleeting impulse to subject my sons to child labor or snatch up an ax and hurl it at them. Fortunately, my grandfather disrupted the pattern. While he could be grouchy, he insisted his children attend college, and as far as I know, never took an ax to anyone.

Grandpa was equally gruff with all 10 of his grandchildren. On the few occasions he was optimistic, he hid it behind a facade of pessimism. When I purchased my house, he would never enter without predicting my eventual bankruptcy. But every now and then, the curtain would part and his nobler qualities would shine forth. He loved children—right up until they could talk, then they annoyed him. Until then, he was the ideal grandpa, balancing babies on his knee and cooing to them in Walloon.

I know there are bad people who immigrate to America and that it’s customary to fear people, cultures, and languages we don’t understand. But the rabid rejection of immigrants we hear voiced today strikes me as hateful and stupid. The immigrant I knew best went to church every Sunday, volunteered as a Boy Scout leader, helped his sick neighbors, and taught woodworking at the Senior Center three days a week. He gave America a school principal, a special education teacher, a farmer, an Army medic, a pro golfer, two nurses, an executive, a marketing expert, a minister, two pharmacists, a salesman, a writer, and a steady stream of college graduates who have improved thousands of lives and paid millions of dollars in taxes. I don’t think that’s uncommon. Indeed, I suspect it’s the norm for every family who has lived in America as long as ours. Which makes me suspect that the ranting and raving about immigration has more to do with the fact that the current crop of immigrants either aren’t as white as my Belgian grandfather or don’t speak Walloon. I wonder which.

Philip Gulley is a Quaker pastor, author, and humorist. Back Home Again chronicles his views on life in Indiana.