Postscript: Marilyn Schultz Opens Her Hate Mail

When an Indiana University student asked to interview her for a term paper on the International Women’s Conference, Marilyn Schultz began digging through her attic. She was looking for a dusty file cabinet crammed with documents chronicling her 14 years in the Indiana General Assembly, from 1972 to 1986, as one of the few female legislators at the time. In her records, she found a single manila folder containing a dozen unopened letters, postmarked nearly 40 years earlier, that she had long forgotten.

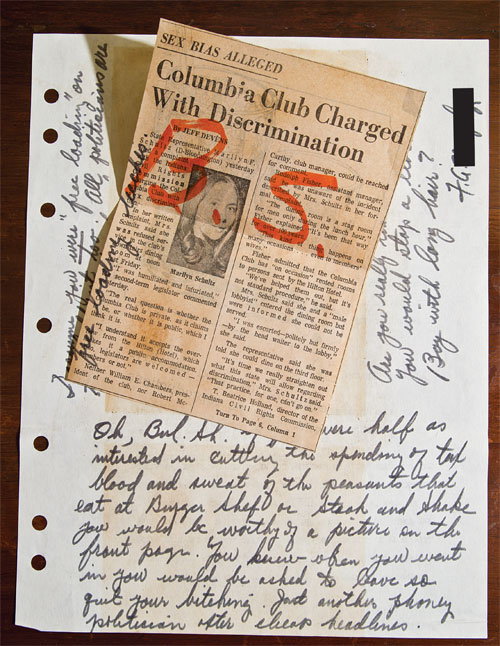

But Schultz knew what they would say. The envelopes were all that remained of dozens of pieces of hate mail she received after making the news for a sex-discrimination complaint against Indy’s Columbia Club; at the time, the club allowed only white men into the main dining room, where legislators often conducted business. “They were in that file because the ones that [arrived] before them were really ugly, and there’s only so much you can subject yourself to,” she says.

Decades later, though, she couldn’t resist. She invited a neighbor over, unsealed the envelopes, and began reading.

“What are you trying to prove? I am getting so sick of women libbers and their equal rights! True, we did need a few things changed, but you carry things too far. If that is all you can accomplish by being our representative, why in the hell did we elect you?”

“Judgeing [sic] from your photo in the Star and later on TV, your vapid and moronic appearance wouldn’t even add any dignity or grace to a Burger-Chef. You would probably even be denied admission to the Columbia Club’s men’s restroom.”

“Too many women are angry with their womanhood and are seeking revenge by demanding equality with man.”

“Are you really that homely? You would stop a clock. Boy with long hair? If you were only half as interested in cutting the spending …”

“We just laughed all afternoon,” Schultz recalls.

Those letters, typed and handwritten, capture a turbulent and unsettling time. On a brisk January day in 1975, months before Time magazine would name “American Women” its Person of the Year, Schultz had made the short and familiar walk from the Indiana Statehouse to the Columbia Club on Monument Circle. The private club, more than a century old, catered to the city’s elite (and mostly Republican) power brokers, and it was a favorite among legislators. On previous visits, Schultz, who wasn’t a member, had headed to the third-floor dining room as the guest of a fellow lawmaker or lobbyist. But on that day, she and the lobbyist were short on time.

Not Yours Truly, “Mrs.”[Redacted] & proud of it too!

SCHULTZ‘S RESPONSE: “When I married, I didn’t take my husband’s name. It was in the middle of an election, but that wasn’t the reason. I just didn’t want to change my name, and the Republican Party went to authorities to see if they could force me to change names.”

Weary Kokomo Taxpayer

SCHULTZ’S RESPONSE: “I remember a Republican legislator said, ‘You must be careful of your reputation. You must never go out in the evening with these legislators.’ And I thought, what am I doing here? The business doesn’t take place on the floor; it’s forming those relationships, [talking about] what legislation is coming up the next day. Those discussions take place out of the chamber.”

So Schultz suggested the first-floor dining room, “where they were used to serving people fast,” she says. But the Democrat from Bloomington, a 30-year-old women’s-rights activist and an ardent supporter of the Equal Rights Amendment, had another motive.

“I thought it would be interesting to see if they would let me in,” she says. They didn’t.

“The maitre d’ said, ‘Madam, you cannot go into the dining room,’ and I said, ‘I’m a legislator, and I thought ….’ He turned me away.”

Not wanting to make a scene, Schultz followed her “mortified” lobbyist upstairs for lunch. But as she walked back to the Statehouse, she was infuriated. “It just burned and burned and burned,” she says. “There were my friends going in, and I was being turned away.”

Like most private clubs in that era, including the Indianapolis Athletic Club, the Columbia Club restricted its membership to white men. During the legislative session, though, it did provide out-of-town female legislators with a “temporary membership,” as Schultz recalls. That gave them access to the hotel and third-floor “ladies’ dining room,” but other parts of the club remained off-limits. “To close down the main dining room where a lot of legislative action took place was to exclude all women and blacks,” she says.

She saw the perfect opportunity to challenge the status quo. She filed a complaint with the Indiana Civil Rights Commission, accusing the venerable club of sex discrimination.

[Unsigned]

SCHULTZ’S RESPONSE: “Women of my generation were told to go to college and get your ‘MRS’ degree. It’s hard [for young people] to understand how radical it was to think a woman could be a doctor, a lawyer, or a legislator.”

Fran [Redacted]

SCHULTZ’S RESPONSE: “Over and over, I heard ‘We don’t want our husbands in a place where there are single women.’ I don’t think anyone would say that today. It’s not part of our consciousness.”

The legislator was primed for battle, but she was unprepared for the backlash that followed. Media across the state covered her complaint, and hate mail poured in. “I was ridiculed,” Schultz says. “Why did I want to eat with all these men? That wasn’t the point. The point wasthat in a democratic society where legislation is being discussed, it should take place in the open, and different legislators shouldn’t be excluded.”

But taking on an old-boys club didn’t help. “You knew everyone in the hall was joking about it,” she says. “It was detracting from everything else I was doing. On the other hand, it needed to be done.”

We are behind you 100%—it’s time these men get put in their place. Our church has a men’s club and they go on a retreat every year. I’m forming an organization to put a stop to such actions. Keep up the good work!” Frankie [Redacted]

SCHULTZ’S RESPONSE: “Women of my age, who went through the transition, we were growing up to get [married], and all of a sudden we were on the cusp of something very exciting.”

Judgeing [sic] from your photo in the Star and later on TV, your vapid and moronic appearance wouldn’t even add any dignity or grace to a Burger-Chef. You would probably even be denied admission to the Columbia Club’s men’s restroom. Your “‘sloppy” hair and otherwise dumb appearance and dumber actions are not indicative of a sincere public representative …”

Thoroughly disgusted,

Mrs.’s MS’s and other “hoi-polloi”

SCHULTZ’S RESPONSE: “Even now when someone wants to attack a woman in politics, they attack her appearance. Think about Hillary Clinton or Nancy Pelosi. It’s always how they look or what they’re wearing.”

The Columbia Club filed a motion to dismiss Schultz’s complaint; the Civil Rights Commission denied it. The club reversed its position under the leadership of its young president, J. Albert Smith Jr., who was 35 at the time. “I wasn’t the most popular person in the room, but it was the right thing to do,” he says. He told members, “The world is changing, and we need to fix this.” And they did.

Soon after, the Harrison Room was opened to women. In 1979, the club accepted its first female member. Women now comprise 25 percent of the Columbia Club’s membership. After leaving the legislature voluntarily in 1986, Schultz held high-level administration posts at the IU School of Medicine, the Mental Health Association of Indiana, and Indiana State University, and then served as the state budget director under governors Frank O’Bannon and Joe Kernan, retiring in early 2005.

Most of the letters Schultz kept show that the push for change came with a price. They seem absurd now—except for one, fairly new to the collection, sent via Facebook three years ago. It’s from a former Bloomington resident whose mother despised Schultz. He wrote to thank her: “It’s because of you … and other women in Bloomington politics that my children live in a world where women justices sit on the Supreme Court, where a partial African-American is the president. You’ve made a difference. Bless you.”

Photos by Tony Valainis

This article appeared in the May 2013 issue.