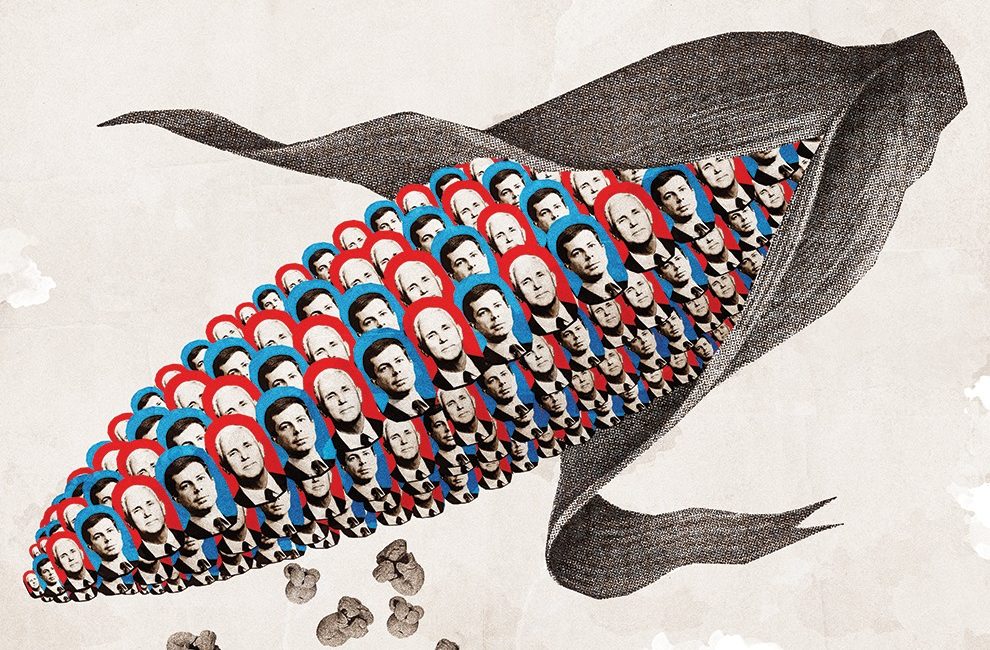

Illustration by Lincoln Agnew

The Looming Fight Between Pete And Pence

“Please don’t judge my state by our former governor,” Pete Buttigieg said.

It was March, and the South Bend mayor and dark horse of the 2020 Democratic primary was standing on a stage at a CNN town hall in Austin, Texas, in the midst of what would later be widely acknowledged as his breakout performance. At the time, he was polling in the single digits and hadn’t yet reached the 65,000 individual-donor threshold he needed to qualify for the Democratic National Committee’s first presidential debate this month.

Then it happened. Audience member James Doty, a gray-haired professor of neurosurgery at Stanford, stood to ask Buttigieg a question about the nature of the Indiana electorate, specifically whether socially conservative Mike Pence, now vice president, was an accurate reflection of what the former governor himself liked to call Hoosier Values. “Among the average voter in Indiana let’s say, are [Pence’s] views an aberration, or is this really representative of the state?” Doty asked. “Or are most people more like you in your more liberal views about us as humans?”

Buttigieg, wearing his trademark white Oxford shirt with sleeves rolled up and a blue tie, stared back at the man and flashed a winsome smile. Then, he delivered the don’t-judge-my-state applause line. The audience clapped and laughed.

But Buttigieg wasn’t done. He briefly explained the Religious Freedom Restoration Act, which in part enabled individuals and businesses to refuse service to LGBTQ people on religious or moral grounds. It was signed into law by Pence in 2015, and Visit Indy believes the piece of legislation cost Indianapolis 12 conventions and $60 million in economic impact; it also caused three governors to ban nonessential government travel to Indiana. The residue of that political and civic explosion is still visible in the pale blue-white-and-red THIS BUSINESS SERVES EVERYONE stickers on storefronts around Indianapolis and the state.

Although they represent completely different visions for Indiana and the U.S., Buttigieg and Pence have some of the same talents on the campaign trail.AP Photo

“The amazing thing that happened in Indiana was that Democrats and Republicans rose up,” Buttigieg continued. “There was a coalition of mayors, business leaders, sports leaders—I think even NASCAR put out a statement saying they were disappointed. And the business Republicans revolted right alongside us progressives. So that shows me that there is a belief in just decency that really does stand against that kind of social extremism. And my hope is that same decency can be summoned from our communities, in red states and blue states, to change what’s happening in the politics of our country before it’s too late.” The audience clapped again.

The moment—chased by a coda in which Buttigieg was asked by CNN’s Jake Tapper whether Pence would make a better or worse president than Donald Trump (“Oof,” Buttigieg grimaced)—arguably flung the candidate into the top tier of 2020 contenders. He raised $600,000 in the next 24 hours, and would go on to post a $7 million quarter. Soon enough, he would place third in most polls of early-voting states such as Iowa and New Hampshire.

But the event also raised a question about the soul of Hoosier politics. It’s a subject discussed at watering holes and feed-and-seeds around the state, and quadrennially around the tables of cable-news panels, where talking heads wonder if, like in 2008, the right candidate could turn the state blue: Is Indiana really as red as its barns?

National coverage of Buttigieg has treated the candidate as a sort of sore thumb in Mike Pence’s Indiana. How did this liberal mayor pop up there, they wonder. But a survey of Indiana’s political history reveals Mike Pence’s Indiana is closer to an aberration than it is the norm. Buttigieg—a progressive pol in a moderate wrapper who talks both about abolishing the Electoral College and solving the national deficit—is really more the mean than the outlier.

When he was preparing a 1968 presidential run that would launch ahead of Indiana’s May primary, Robert Kennedy requested a memo from the writer and political aide John Bartlow Martin. He wanted to know the political hue of the electorate here. Hoosiers, Martin wrote, were “conservative in fiscal matters.” He added that we’re “phlegmatic, skeptical, hard to move, with a ‘show me’ attitude.” In other words, Hoosiers might be conservative, but we’re conservative in a way that worries more about the height of the corn by the Fourth of July than about what the person across the street prefers in the bedroom. In the same way that Hoosier farmers don’t like swings in weather because it might damage their crops, voters here don’t seem to like political extremes. (Our initially high support for Trump might be one exception. But according to Morning Consult, his approval rating here has dropped 19 points since January 2017. As of March, 50 percent approved and 47 percent disapproved.)

Take Wendell Willkie, for example. The Democrat-turned-Republican attorney and corporate executive from Elwood, who ran for president in 1940, was lauded for his up-the-middle—even progressive—stance on social issues. Like Buttigieg, he was labeled a dark horse. He pledged to integrate the armed forces. As of 1942, he was the highest-ranking politician to address the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, leading the organization to name their headquarters in New York the Wendell Willkie Memorial Building.

Another Indiana politician, former Governor Mitch Daniels, made his mark as a possible presidential candidate in 2012 by calling for a truce on social issues in 2010 in order to right the nation’s fiscal house. “We’re going to just have to agree to get along for a little while,” Daniels told a reporter from the conservative magazine The Weekly Standard.

When current Governor Eric Holcomb ascended to the office, political prognosticators asked whether he would be a social conservative warrior or a more meat-and-potatoes, Chamber of Commerce Republican. “Is Eric Holcomb a Daniels or a Pence?” read the headline of a July 2016 Indianapolis Star column by the late Matthew Tully. Holcomb, it turned out, has been more of a Daniels, and voters have rewarded him. As of January, according to Morning Consult, only 22 percent of Hoosiers disapproved of his job performance.

In that same vein, Buttigieg’s socially progressive, fiscally moderate approach might be why he is so popular among a certain kind of voter in Indiana—and elsewhere. This spring in Indianapolis, a sizable crowd gathered for a watch party of his town hall, and he sold out an IUPUI event for his book signing in February. Here, he enjoys the affection of upwardly mobile, fiscally conservative and socially liberal young professionals—the kind of people you would find drinking a craft beer at Liter House, a nouveau-Bavarian restaurant that unveiled a Buttigieg-inspired altbier in April. Much like a well-balanced beer, Buttigieg—and the pushback he has waged against the vice president—offers something of a palate-cleanser to people still recovering from the reputational black eye RFRA and the Pence years dealt the city and state. Buttigieg, in a way, presents the state in a new-old light.

At their core, politicians often become, for better or worse, a personification of the states and locales they represent. Find a more Bronx pol than Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez. Try to out-Texas the swagger of a George W. Bush or Lyndon B. Johnson. And for the last four years, so it has been with Pence, whom the U.S. Secret Service has even given the codename “Hoosier.” His milquetoast, aw-shucks passivity seems to capture the Hoosier ethos—or at least the perception of the

Hoosier ethos folks on the coasts have.

So when Doty, the neurosurgeon, asked Buttigieg who truly represents our state? People will be doing that a lot more, especially if Buttigieg and Pence eventually end up on a vice presidential debate stage together next fall. (It’s also possible, of course, that Buttigieg could find himself facing Trump). History would appear to favor the former match-up. Indiana is known as the “Mother of Vice Presidents,” producing six. It could be a Hoosier battle royale, one that pits the gay Episcopalian war veteran mayor against the evangelical former governor who has been called a homophobe. Both can and do cite scripture in their appeal to voters. Those traits exemplify the political tension in the state. “There’s always been this yin and yang in Hoosier politics,” says Ray Boomhower, the Indiana historian. “You have the dichotomy between our conservative reputation and a lot of progressive individuals who represented the state,” including figures like Senator Birch Bayh, Representative Julia Carson, and Senator Vance Hartke.

What remains in the short term is an interesting fight for the political soul of the state, a test case of what it means to be a Hoosier—at least in the political sense. At times, we have been both the aw-shucks guys and the surprising progressives here. Buttigieg’s and Pence’s is a death match to determine which view will hold—for now.