Leaps of Faith: Sandy Sasso's Story

Editor’s Note, May 14, 2014: Sandy Eisenberg Sasso was the first woman ordained as a rabbi in Judaism’s Reconstructionist movement. On June 12, she is to receive the prestigious Heritage Keeper Award at the annual Tribute Dinner at the Indiana State Museum. The award is given to “Indiana’s greatest ambassadors for their embodiment of the Hoosier spirit in their accomplishments, leadership, and service to the state.” Rabbi Sasso will be the fourth honoree. Those previously honored include Richard Lugar (2013), Earl Goode (2012), and the Hulman-George family (2011.) Until her 2013 retirement, Rabbi Sasso and her husband, Rabbi Dennis Sasso, were the senior rabbis at Beth El Zedeck locally—the first married pair to serve jointly as a congregation’s rabbis.

When my husband Dennis and I came to Indianapolis in 1977 to serve as spiritual leaders of Congregation Beth-El Zedeck, I wondered what Midwestern wasteland awaited me. I was born and educated in Philadelphia and worked as a rabbi for three years in Manhattan. As we drove from the East Coast to our new home in Washington Township, I listened to the car radio. The news was about the latest soybean and pork-belly futures report. I turned to Dennis and said, “Where in the world are we going?”

Having delighted in mountains and oceans, I was worried about being landlocked in a city that from an airplane looked like a pop-up picture book. But it was more than the geography that concerned me. I wondered how a Jewish community could possibly thrive in the Bible Belt. And if being Jewish made me an oddity in a landscape of church steeples, would being a female rabbi in a flatland of religious conservatism brand me bizarre? I envisioned myself in a city of white bread and sweet corn, when my soul yearned for thick-crusted rye and sweet rugelach.

Dennis and I were the first rabbinic couple in Jewish history. We met during our first year at Philadelphia’s Reconstructionist Rabbinical College and married less than a year later. The day after the wedding, our picture appeared on the front page of the Philadelphia Bulletin. The caption read: “2 Rabbinical Students Are Wed: Ceremony is ‘Historic’ in Judaism.” Though I was a rarity—the first woman to be ordained from the College—Dennis never questioned my decision to become a rabbi. For three years, we served separate congregations, Dennis on Long Island and I in Manhattan. Then Congregation Beth-El Zedeck in Indianapolis invited Dennis to interview. The congregation was even attracted by the option of us serving together. But our son, David, was only a year old, and responsibilities at a large synagogue like Beth-El Zedeck required a seven-day commitment. I offered to work part-time so that I could be more involved in raising our family. When David and our second child, Debbie, began school, I became a full-time rabbi.

Back then, some in the synagogue wanted me to become the principal of the Religious School instead. But while I loved teaching and kids—and could supervise the educational programming—I was a rabbi. I wanted to be an educator and a pastor, preacher, and community representative. Sunday-school director was an “acceptable” position for women, but not the one for which I had studied. There had to be doubts about a woman performing rabbinic functions, but the congregation decided the risk was worth taking.

Now, after three-and-a-half decades at my rabbinical post, I will retire this month from Beth-El Zedeck—a career that was once just the dream of a shy teenager.

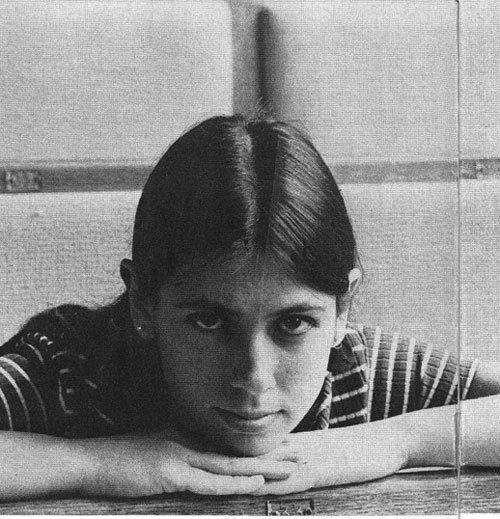

I remember where I was, the day, the place, the emotion, when I decided to become a rabbi. It was night; the rest of my family was in bed. I couldn’t sleep. The room could have belonged to any 16-year-old girl of the time: two single beds with white spreads, a pink princess phone, a small vanity, a rarely played guitar in the corner. I sat on the edge of one of the beds; my heart raced. I said to myself, “I want to become a rabbi.” It was May 1963, and there were no female rabbis in the United States.

Later in life, people would ask me when I was “called.” Most of my career, I would answer, “Ministers and priests speak of being called, not rabbis. My decision was a rational one, a result of my profound interest in Judaism.” I delighted in the rhythm of the year, the poetry of ritual, the metaphors in prayer. As a teenager, I loved that we struggled with big questions, and that doubt and uncertainty were part of the faith journey.

But the desire to become a rabbi was much more than a reasoned decision. I don’t think that something from on high was calling out to me, but something from inside was, pulling and drawing me to an unknown place. It was a spiritual calling, exhilarating and frightening at the same time. My maternal grandfather was secular; my paternal grandmother was Orthodox. Neither could understand my choice, but they never said a word. My parents fully supported me.

When I started seminary in 1969, Jewish feminism was an oxymoron. There were still no female rabbis in this country, although I was aware that Sally Priesand, who would be the first woman to be ordained in the United States, was studying at Hebrew Union College. I bought every Ms. magazine, hoping it might speak to my concerns. Most of the editors of the magazine, after all, were Jews. There were articles about politics, business, and professions like law and medicine, but nothing about religion. I felt ill at ease in this emerging feminist culture that did not address my Jewish soul, but I also was beginning to feel marginalized by the Jewish community because it did not embrace my woman’s soul. Let me offer you a glimpse of what it was like in those early years.

Some months into my first year of seminary, I received a letter from a woman I had never met but who had read an article in a Baltimore newspaper about my decision to become a rabbi:

“Frankly, I just can’t understand what would prompt a Jewish girl to have the ‘Chutzpah’ to consider herself eligible to become a rabbi. … The very idea of a female rabbi makes me sick. And my first reaction was, ‘she must be nuts.’

“Still you look pretty enough in the picture, and being Jewish, I am just prejudiced enough to figure that you are smart, too—so, I am hoping that you will do a very great deal of studying, and somewhere along the line, you will find out that you are pursuing a wrong goal, and you just might back up and end up on the right track after all—I sincerely hope so.

“Ordinarily, I would sign off by wishing much success, but this time I will refrain—in fact, frankly, I hope you don’t make it—for your sake, mine and everyone else’s.”

That reaction wasn’t unusual. During those years, I was invited to speak before many audiences. After I made an impassioned plea for the importance of women in the rabbinate at one such lecture, a middle-aged man in the audience asked, “Can you make chicken soup?” I’d like to tell you that I dismissed the question as impolite. But the next day, I went to the supermarket and bought chicken, celery, carrots, and onions, and came home to prove to myself that I could be a rabbi and make chicken soup.

Just before I was to be ordained, I was asked to speak by the sisterhood of a large synagogue in my community. After my presentation, the rabbi stood, and instead of the traditional “Thank you for coming” and “Mazal Tov on your ordination,” he said, “When you grow up, you’ll change your mind.” (A footnote: I didn’t, but he did. He eventually voted in favor of the ordination of women in the Conservative movement.)

“After I made an impassioned plea for the importance of women in the rabbinate at one such lecture, a middle-aged man in the audience asked, ‘Can you make chicken soup?’”

“After I made an impassioned plea for the importance of women in the rabbinate at one such lecture, a middle-aged man in the audience asked, ‘Can you make chicken soup?’”Finally, the first New York congregation at which I interviewed told me that they were ready to consider a female rabbi. I led services, taught, and worked with the children of the religious school. Then I interviewed with the search committee. The first question? “What happens if you become pregnant?” Wryly, I replied that my husband and I believed in “Planned Pulpithood.” I did not get that job. Instead, I was elected by a small Manhattan synagogue, which welcomed me and celebrated with me when I gave birth to my first child.If New York, a city in which change is expected and embraced, was reluctant to accept a female rabbi, how much harder would it be in Indianapolis? Yet I soon discovered that Indiana was home to the first two women to be regularly ordained as Episcopal priests: Reverend Jackie Means, who served as a prison chaplain, and Reverend Tanya Vonnegut Beck, who led Communicators Inc. and served as a part-time priest in Speedway. I invited them to be part of my and Dennis’s installation at Beth-El Zedeck, and they became dear friends. I also helped form the Women’s Interfaith Table, to bring together women of different faiths interested in

feminism and religious leadership, and a large number of people joined. I found in Indianapolis, where I least expected it, women I could call sisters in spirit, including Judge Sarah Evans Barker, a powerful champion and supporter of professional women, and a cherished friend.

At my own post, I came to realize that my goal was not just to fit in at Congregation Beth-El Zedeck, but also to bring who I was to the rabbinate. Being a woman was not the only point, but neither was it beside the point, as I had first thought. So I listened to the voices and silences on the margins, in the biblical texts, in the cycle of people’s lives. For instance, a woman in my congregation had a miscarriage late in a pregnancy. When it was clear that tradition had no ritual or liturgy to give voice to her grief, I created a prayer, a sacred vessel to carry the pain.

I also brought a mother’s perspective to family counseling, an outsider’s understanding to building an inclusive community. Throughout the congregation’s history, no woman had been asked to hold a Torah during the chanting of the Kol Nidre, the opening prayer of the holiest day in Judaism, the Day of Atonement, Yom Kippur. Dennis and I changed that. At every bar or bat mitzvah Friday-night service, the girls recited the short blessing over candles and the boys chanted the longer blessing over the wine, the Kiddush; I altered the requirements—girls and boys would do both. Now no one questions a woman holding Torah, a girl chanting Kiddush, a boy saying the candle blessing; it is tradition.

There were times when the feminist movement would have wanted me to be more strident and less enamored of tradition, while the Jewish community, more traditional and less feminist. What I sought was balance. Now there are very few prayer books that are not gender inclusive. When I started, there were none. In fact, when a baby girl was born to one of our rabbinic colleagues and his wife in 1973, my husband and I created a ceremony to welcome girls into the covenant of the Jewish people. When we performed the ceremony again in Evanston, Illinois, it was so unusual that it made the newspapers. Now, liturgies welcoming girls into the covenant are commonplace.

Several years ago, I met with a group of women to talk theology, and I asked them to find their own name for God. One woman said, “I would like to call God an Old Warm Bathrobe.” I thought it a bit strange but thanked her for sharing. One year later, that same woman came to thank me for the exercise. “My mother died this last year,” she said, “and I wrapped her old warm bathrobe around me and felt the presence of God.”

Women like her are naming God, interpreting the Bible, leading congregations, serving communities, working as chaplains, rethinking theology, reshaping liturgy and ritual. What has happened in just four decades is nothing short of a revolution. A member of the congregation recently honored my service, saying, “When Rabbi Sandy first came to Indianapolis, people could not imagine a woman on the bimah [pulpit]. Now no one can imagine this bimah without Rabbi Sandy.”

In some ways it’s hard for me to imagine myself leaving the bimah, too. The time that Dennis and I have lived in Indianapolis has made us proud to call ourselves Hoosiers. That is quite an accomplishment for a girl from the East Coast and a boy who was born in Panama. Here is where our two wonderful children learned to walk and where we found the education and love that enabled us to excel in our careers and to build our family. And for 36 years, I have had the true pleasure of working alongside my husband at Congregation Beth-El Zedeck.

Ours has been a unique and extraordinary rabbinic partnership. Dennis kept me calm when I confronted opposition, and he helped me believe in myself. When critics were harsh, or when they made it clear they did not want me at a ceremony because I was a woman, Dennis reminded me that it was their problem, not mine. People often asked how we managed to spend so much time together at the congregation and at home, to negotiate roles and differences of opinion. We never set out with hard-and-fast rules. We each naturally gravitated to those programs that matched our talents and our interests; on Sundays he would teach conversion classes and I, bar and bat mitzvah family seminars.

Our personalities complement one another, too, and enrich the way we lead and serve. Dennis is a superb lecturer and punster; I am a teacher and a storyteller. I weave narrative with a poetic sense; Dennis writes clear prose. We might not always agree, but we care deeply about our work and about each other. We edit each other’s sermons, are each other’s kindest critic and strongest supporter. I kick him under the table when I can see he is getting frustrated at a board meeting. He helps me relax when I am upset. We make each other better people and better rabbis. We are each other’s beloved and closest friend. In my last High Holy Day sermon to the congregation, I said to Dennis, who will continue to serve at Beth-El Zedeck, “I may not always be on the pulpit with you, but I will always be at your side.”

My life has intersected with generations of congregants, whose own stories of courage, resilience, and hope helped shape my spiritual journey. How can you not be transformed when you touch life’s fragile boundaries? You officiate at a wedding of a woman, handicapped by a stroke, and a man who is paralyzed, confined to a wheelchair, and then watch the bride sit in her groom’s lap and dance. You bless babies with whom you later stand as they become bar and bat mitzvah. Then you bless them again as brides and grooms under the wedding canopy. In time, you hold their babies, who in turn read Torah as b’nai mitzvah.

I once held a silver Kiddush cup at a wedding. The cup was the only item Mike, the father of the bride, had been able to retrieve from his home in Poland after the Holocaust. He was 5 years old when he was liberated from Auschwitz. Of his family, only Mike, his mother, and his grandmother survived—and that cup. Years later, I had the privilege of standing under the huppah [wedding canopy] with his daughter, a new generation that was never meant to be, and we filled that empty cup with sweet wine and said, “L’chayyim!” [“To life!”].

Another time, I asked children at a Yom Kippur family service what their favorite name for God was. A 5-year-old boy said, “I want to call God, Healer.” His mother, you see, was dying of breast cancer. On Yom Kippur some 20 years later, I told my congregation how that prayer altered me, taught me something about faith I had not known. After services, that boy, now a young man studying astrophysics, came to greet me. I asked, “Did you recognize yourself in my sermon?” He said, “Yes, that little boy, that was me.” I said, “I will never forget that name or that moment.” He looked at me and said, “Neither will I.”

That is what happens when you have the privilege of serving a congregation for more than three-and-a-half decades. You make friends, are with them when they succeed and when they fail, and write eulogies for people you love and admire. You realize what matters in the long run—a good word, a warm embrace, presence. You give up being certain, the illusion that you are in total control, and you learn grace and hope. You realize why the most common sentence in the Bible is “Do not be afraid, because I am with you.” Nothing matters more than that; nothing is more sacred.

I never could have imagined that coming to the city of Indianapolis, of which I knew little except that some kind of car race took place here, would change my life—would give me moments like that. I have come to love this city, its culture, and its Jewish life. To my own astonishment, I have even come to cheer its sports teams—the Pacers, the Fever, the Colts, Butler and IU basketball. When we first moved to the northwest side, though, I remember asking my mother to promise to bring a kosher brisket fromPhiladelphia when she visited. For years, she kept her promise, packing an eight-pound frozen hunk in the front flap of her suitcase. (I remain eternally grateful to the airlines for never losing her luggage!) While still no one knows what a corned-beef special is, and I am forever searching for my favorite East Coast whitefish salad, at least we can now buy kosher meat and chicken at local supermarkets.

I have come to care deeply about the future of Indianapolis, its problems, and its vision for overcoming them. There are matters that require attention: hunger, healthcare, transportation, education, caring for those who are marginalized. But there are also people who are trying to create change, who fashion venues for civil conversation, who believe that diversity enriches us, that culture is good for the soul and for business. Being the first female rabbi in Indianapolis, I have been afforded opportunities to be part of this work in ways I could never have imagined. In a class at Christian Theological Seminary, I found the inspiration to begin writing books for children, beginning with God’s Paintbrush. In a neighborhood restaurant on the north side, I connected with an extraordinary group of authors who expanded my mind and encouraged me in my writing. And my work with interfaith groups has taught me that people of different faiths can learn about one another and work together for a common goal. In 1996, the Spirit & Place Festival was born and brought an incredible week of programs that marked a collaboration of religion, the arts, and the humanities. It was my privilege to be able to chair the program during its early years.

Gertrude Stein once said, “A very important thing … is not to make up your mind that you are any one thing.” I have just retired as senior rabbi of Congregation Beth-El Zedeck and have become rabbi emerita. Gertrude Stein was right; we are more than one thing. This is a time for re-envisioning; a chance to write more; to explore the intersection of two of my passions, religious texts and artistic expression, and what, with more time, I might yet do in this city I call home. I also will direct a new Religion and the Arts program at Butler University in partnership with Christian Theological Seminary and engage more in teaching, speaking, storytelling, and community service.

I will miss walking people through the life cycle, counseling, giving sermons. But you never stop being a rabbi, a teacher, a friend, a person who cares about the lives of others. When you retire from the congregational rabbinate, you just start doing those things in different ways. To paraphrase the poet Carl Sandburg: I may keep this youthful heart of mine. I am an idealist. I don’t know fully where I am going, but I am on my way.

Photos by Tony Valainis

This article appeared in the June 2013 issue.