Phil Gulley: What I’m Thankful For

This month will bring with it my 57th Thanksgiving, each one lodged in my memory, including my first, when I sat on my mother’s lap at the age of 10 months and was spoon-fed mashed potatoes. How is it, you might ask, that a man can remember what he ate when he was 10 months old? You have obviously never eaten my mother’s mashed potatoes with turkey gravy. Mom is gone, and her gravy with her, but my wife had the good sense to ask her for the recipe while my mother lay dying. “And for God’s sake, no giblets,” Mom said, then slipped away to glory, her earthly mission done.

In my early years, my father cooked the Thanksgiving turkey on a Weber grill in our barn, a deeply spiritual experience for him. He attended no church, paid no heed to organized religions, but believed mightily in the redemptive powers of the properly cooked turkey. For someone who devoted so much time to the preparation of turkey, my father was remarkably casual about its acquisition, cooking whatever Mom brought home from Johnston’s IGA, usually a bird pumped full of steroids and antibiotics, raised in a sweltering, smelly shed in Southern Indiana with a million other miserable birds. My father was an excellent cook, but I could always taste a trace of turkey despair even the seasonings couldn’t mask.

There are varying schools of thought regarding the best time to consume a turkey. Some prefer theirs hot from the oven, while those with a less refined palate favor day-old turkey in soups, casseroles, and potpies. I am a hot-from-the-oven man, and thus detested the family prayer that stood between me and nirvana. My grandmother Gulley, an ardent Baptist, was our chief prayer, who believed the effectiveness of one’s prayer was directly related to its length. So she would go on and on, beseeching the Lord to do first one thing and then another, as if God were seated at the table taking notes. When I became a pastor, the duty switched to me, and I single-handedly reduced our prayer time by 90 percent, assuming that God was well-acquainted with our needs and didn’t require reminding. Then my brother got religion, took over praying, and we were back to long devotions, indeed entire Bible studies and altar calls, delivered over cooling turkey and congealing potatoes, until one Thanksgiving I wrested it away from him and have delivered it ever since. My house. My prayer.

The move to our house was not without difficulty. One doesn’t shift a Thanksgiving locale overnight. Negotiations are held, compromises made, assurances given. Our change in location occurred in 2005, when my parents moved from their big house on Broadway Street to their little house on Appleblossom Way, a dwelling too small to accommodate 30 people. My wife, the family organizer, convened all of us in late summer to seek a way forward. One of my brothers, the praying one, offered to host Thanksgiving. This was met with alarm, since he and his wife are vegans, eating things God never intended us to eat, various roots and beans shaped and colored like real food in order to trick us. My other brother lives in an apartment (too small), my third brother lives in North Carolina (too far away), and my sister has annoying cats, so the family Thanksgiving dinner settled upon our home, where it remains, these many years later.

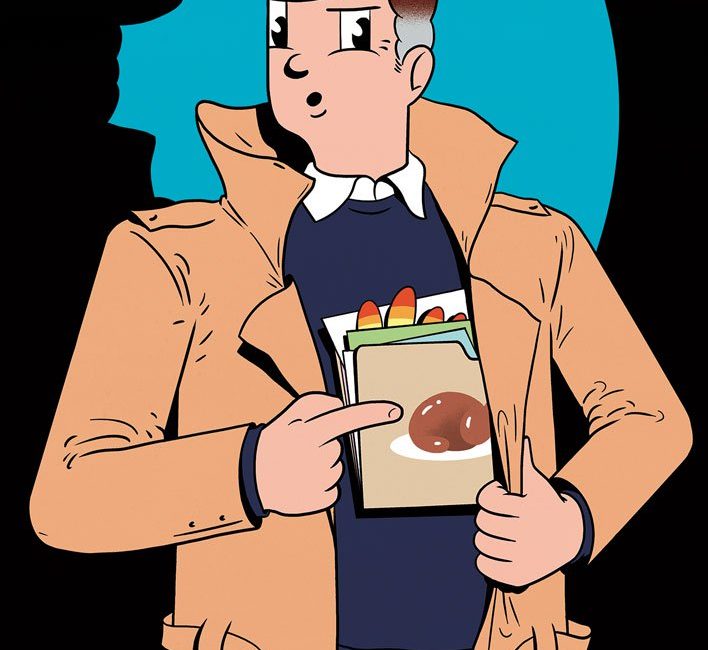

My wife grew up on a farm in Southern Indiana and is very familiar with the niceties of the Big Family Dinner, which is what they’re called in my family—BFDs, for short. Food was the chief curative in her family, her parents having a general mistrust of physicians and little money to see one. Homemade chicken soup for colds, meat for the weary, hickory nuts for the constipated, and corn on the cob fresh from the garden for the cynical, causing doubters to believe once more in the providence and grace of God. So I was not surprised when my wife announced last Thanksgiving that she would no longer purchase frozen turkeys from Kroger with a little red stick that popped up when done, but from a young man in our town named Tyler Morelock, whose turkeys were three times the cost of Kroger’s turkeys and 10 times better.

I grew up with Tyler’s father, Wes. In fact, I was born the same day, February 5, 1961, and during our elementary years, we stood side-by-side while our classmates sang “Happy Birthday” to us. Wes and I are intrinsically linked, first by birth and now by the collusions of family that unite us at the altar of the turkey, Wes’s offspring feeding mine.

To be a turkey raised by Tyler Morelock is to know nothing but pure bliss from birth until the moment of execution. Free to gorge themselves on corn and bugs and the errant pebble to aid digestion, free to roam the pasture, conversing with the cow, the pig, the goat. Then, weary and content, in the dog days of summer, free to nap in the shade of the oak tree beside the barn. The month of November arrives, but the turkeys are blessedly unaware, Tyler having made no mention of the holiday and its dietary customs. In the few days before Thanksgiving, a last generous meal is served, then death is administered, quickly and painlessly. We should all hope to expire so peaceably, our stomachs full, our minds at ease.

The day before Thanksgiving, Tyler’s turkeys are distributed, wrapped in clean white butcher’s paper. Just the turkey, no instructions. Tyler has a high opinion of his customers and assumes they are bright enough to cook a turkey without his guidance. I have no idea what my wife does to the turkey, since I am banished from the kitchen. In my family, to disclose your culinary mysteries is to promote insurrection by rendering yourself useless. The best secrets are saved for the deathbed. So while I don’t know what she does to the bird, I approve of it and am happy to remain ignorant, though I often pray she doesn’t die suddenly, struck down by a truck or heart attack before passing on her body of knowledge.

My siblings and I are now the age my aunts and uncles were when we were children at family Thanksgiving. The family elders. Our children defer to us, making allowances for our age, speaking loudly and slowly at us, as if we are holding ear trumpets. I know what they’re thinking when they look at us, that before they know it, probably in the next year or two, we’ll be dead and they’ll be hosting Thanksgiving dinner. They ask how the mashed potatoes are made, wondering aloud about the yeast rolls and how my sister gets them so puffy and soft. We are tight-lipped. “We’ll tell you when it’s time,” we say. “And not until.”

They circle above us like vultures, watching for the little red stick to pop up, signaling that we’re done.