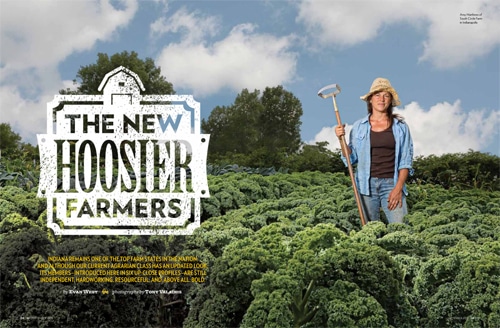

The New Hoosier Farmer: Is a City Girl

Amy Matthews saunters down a mulch pathway wearing a tank top and a camp shirt, cargo capris, and sporty walking boots, past neat rows of lush, leafy kale, teeming tomato plants, and bushes of blackberries so plump they could burst. A breeze loosens wisps of chestnut hair from beneath her floppy straw hat. If you believe that Indiana farmers are weather-hardened old men who grow corn and soybeans, you might look at these tidy patches of naturally raised produce and see a garden—and, in the pretty thirtysomething who tends them, a gardener. But then Matthews kneels down, tugs a purple carrot from the ground, and holds out the prize. And you notice her fingers: thick, with soil-scoured callouses, black loam ground into every crease and under each nail. These are not the hands of a gardener. “Oh,” she says, raising her voice over the grumbles and beeps of heavy machinery at the two scrap-metal processors next door. “You probably don’t eat food with dirt on it.” But you do. And it is delicious.

Matthews started South Circle Farm in 2011, on just under 2 acres of abandoned city lots a couple of miles from the center of downtown Indianapolis. Making a fuss over a woman’s dirty hands might strike you as old-fashioned (Look, Pa, a lady farmer!). But it wasn’t so long ago that a woman taking the lead in an agricultural enterprise was relatively rare in this state. When the U.S. Census of Agriculture first counted farms with female operators in 1978, they made up only 3 percent of the total. At last count, in 2007, roughly one in every 10 farms in Indiana was manned by a woman.

But other aspects of Matthews’s bio make her seem an unlikely farmer, regardless of gender. She grew up on the south side, in a middle-class subdivision; her father worked in retail, her mother at the local schools. Matthews’s only exposures to agriculture were visits to nearby Adrian Orchards and family car rides along Bluff Road, past what was left of a once-thriving produce industry. Marion County was home to 3,437 farms at the turn of the 20th century (compared to fewer than 300 now), and as recently as the 1940s, a collective of growers on the southwest side was reputed to have the highest concentration of commercial greenhouses in the country; the area’s open-air “truck farms” delivered freshly grown goods as far away as Chicago and St. Louis.

It wasn’t until after Matthews left for college in the late ’90s that she noticed how rapidly agriculture was losing out to strip malls and housing additions. “Every time I’d come back as a young adult, I would notice it more, especially when the orchard got bulldozed,” she says. “That was a bummer.” (Much of the original southside property of Adrian Orchards, established in 1925, is now a subdivision called Orchard Park.)

But Matthews still had a long row to hoe before doing anything about it. An early career in hunger-related social work awakened her to small-scale, sustainable agriculture. On travels in the developing world, she came to admire subsistence growers who fed families from harsh soil, using little more than ingenuity and sweat—the man in Nepal, for example, who had devised a gravity-and-mud irrigation system for his sub-Himalayan fields. A stint at a remote organic farm in Montana followed, where Matthews earned $120 a week, slept in a barn, and “learned the agrarian lifestyle.”

“At the time, I knew more cultural references,” she says. “We’d be working, and I’d mention a television show like Seinfeld, and they’d go, ‘What’s that?’”

Ultimately, Matthews wanted the best of both worlds, earthbound and urban. From Montana, she bounced to inner-city growing programs in Chicago and Cleveland—two hotbeds of urban farming. After a soul-searching interlude in Alaska, she was ready to stay put. But when she returned home, she discovered that urban farming in Indianapolis was way behind the Midwestern cities where she’d cut her teeth, with their incubator farms and formal training for would-be growers, programs that put space left empty by Rust Belt decline back to good use (and increased the availability of fresh, local food).

With a couple hundred parcels of vacant, trowel-ready land on its own books, Indianapolis presents a similar opportunity, one that a small but tight-knit community of urban growers has only recently begun to exploit. In the fall of 2010, a community-development corporation offered Matthews the chance to put down roots on a cluster of trash-strewn lots, rent-free, for three years. She had to build the farm from the ground up—literally. Lead-based paint and God-knows-what-else had rendered the soil unusable, so she blanketed it with salvaged cardboard and covered that with a two-foot bed of mulch. Then she bought 76 truckloads of dirt from a southern Marion County farm and mixed it with compost. A metered tie-in to a fire hydrant feeds a gridiron of irrigation tubes.

Matthews now deploys a hodgepodge of organic, “bio-intensive” techniques, coaxing as much produce—lettuce, broccoli, onions, peppers, strawberries, melons, beets, and other varieties too numerous to list here—from her tiny growing area as nature will allow. She rotates crops and follows harvests with weather-appropriate second and third plantings that stretch the growing season from February to December. She uses only hand-powered tools, no herbicides or pesticides, and “pays” a handful of volunteers in vegetables for weed-pulling and other chores.

The city’s database of urban farms and community gardens, which included just 35 entries at the end of 2010, has since swelled to more than a hundred. But for scale and productivity, Matthews is in a class by herself. “She is, in our minds, the first ‘farmer,’” says April Hammerand of the Food Coalition of Central Indiana. “Amy has taken it to another level.”

Very small farms (between 1 and 9 acres) are one of the fastest-growing segments in Indiana agriculture, more than doubling in number over the past three decades. Eventually, Matthews wants her operation to serve as a model for urban planters (which is why she is reluctant to reveal her modest bottom line, for fear of discouraging like-minded entrepreneurs). For now, she covers her costs by supplying local restaurants, selling at markets and a co-op grocery, and signing up CSA (community-supported agriculture) subscribers who pay for weekly bins of produce. As demand for local food grows, she’s hopeful that she—and new farmers who follow her lead—will be able to keep up, maybe allowing Matthews to pay herself a school-teacher’s salary someday.

And after three years of working sunup-to-sundown, she’s starting to understand the blissful pop-culture ignorance of those farmers she knew in Montana. “I’m like them now,” she says. “People come out here to help me, and they’ll tell me something, and I’ll be like, ‘I don’t know what you’re saying.’ In a noisy world, having constant tasks makes the noise a little quieter.”

This article appeared in the September 2013 issue. Read about more New Hoosier Farmers here.