The New Hoosier Farmer: Wants to Feed You Better

The Seattle set was skeptical about Matt Ewer and Beth Blessing’s plan to return to Indiana and start a business delivering fresh, organic produce. “You guys are crazy,” the Seattleites said. “They eat hotdogs and beanie weenies and baked beans for every meal.”

Ewer and Blessing had attended Indiana University in Bloomington, where Ewer—whose family owned a 1,600-acre farm outside his hometown of Marion—worked for a small organic grower. The couple moved to the Pacific Northwest in 2003 so Blessing could pursue a master’s degree in science in nutrition at Bastyr University, near Seattle. They married, and Ewer got a job at a 350-acre organic vegetable farm just outside the city. He knew that, eventually, he wanted to make healthy, sustainably raised food available to people in his home state. And he had a knack for selling vegetables: As a kid, he used to pull a wagon from door to door in his neighborhood, hocking sweet corn.

Ewer’s West Coast pals had good reason to be skeptical: Indiana’s organic industry was lurching ahead in starts and stops. Indiana Certified Organic (ICO), established in 1995, was one of the first inspection and sanctioning companies accredited by the USDA, and its founder, Cissy Bowman, helped shape the federal agency’s regulations. But in 2002, the first year the USDA offered certified-organic designations, Washington, a state with close to the same population, had four times as many organic farms, with more than 20 times the annual sales. And Indiana, despite being one of the most productive agricultural states in the country, still doesn’t grow much food that Hoosiers actually eat. In 2007, vegetables accounted for only about 1 percent of Indiana’s agricultural output. Last year, we raised 597 million bushels of corn, 224 million bushels of soybeans, and 20 million bushels of wheat—roughly 7,000 pounds of grain for every man, woman, and child in the state. And yet, according to a report commissioned by the state health department, we import about 90 percent of the food we consume.

So where Seattleites saw a food desert, the couple from Indiana saw a wide-open marketplace. “The Midwest is the land of milk and honey,” says Ewer. “We’re in Generation X, and we were taught that whether you’re an accountant, or a lawyer, or a farmer, whatever industry you’re in, it’s so big you can’t change it. You just get in the pipeline and do what you’re supposed to do. But the food entrepreneurs—that platform is just too powerful to hold down. It’s too creative. There are all these different outlets coming up, and they’re run by 30-to-40-year-old people.”

Ewer and Blessing (who hails from Noblesville) came back to Indiana in 2006 and, in 2007, launched what is now known as Green BEAN Delivery in Indianapolis. The company sources natural and organic vegetables, fruit, dairy products, and meats (as well as preservative-free, locally processed foods like salsa and veggie burgers) from about 100 growers and artisans—more than 40 of them in Indiana—and then bundles them in plastic bins and brings them to your door. Subscribers can customize their orders online, adding, say, all-natural chicken from Gunthorp Farms in LaGrange; chevre from Caprini Creamery in Spiceland; or cabbage from This Old Farm, a co-op of Central Indiana growers. When Midwestern produce is out of season, Green BEAN (an acronym for “biodynamic, education, agriculture, and nutrition”) sources organic fruits and vegetables from warmer U.S. climes.

It was a concept whose time had come. In the decade leading up to Green BEAN’s inception, sales of food directly from Indiana farmers to consumers had risen by about 70 percent, an indication that Hoosiers were already warming up to the farm-to-table trend. Green BEAN found fertile ground in consumers’ blossoming desire to know where food comes from and their newfound fascination with the “farming lifestyle”—a reaction to the industrialized agriculture that has come to dominate America’s heartland.

“We had set goals,” says Blessing, “and what shocked us was that all those goals we had set for five years were happening in the first year.” After six years in business, Green BEAN has averaged 30 to 50 percent annual growth; signed up more than 6,000 subscribers in Central Indiana; and expanded to Ohio, Missouri, and Kentucky. The company is set to do $15 million to $20 million in sales in 2013. A spinoff, Tiny Footprint Distribution, supplies local goods to grocery stores.

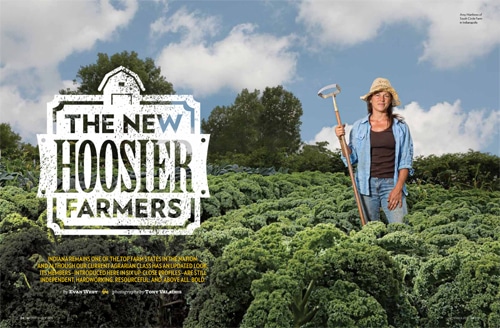

If anything threatens to slow down Green BEAN, it’s lack of supply. “The biggest hole that we see right now is the local produce,” says Ewer. He and Blessing, now in their mid-30s, have taken it on themselves to pick up the slack. First planted in 2010, The Feel Good Farm is a 60-acre, certified-organic growing operation near Sheridan, where the suburban sprawl of Hamilton County gives way to a flat landscape of fields, fencerows, and barns.

Situated on a family farm that used to grow corn and soybeans, Feel Good, with its weedy (no herbicide!) patches of peppers, watermelons, tomatoes, eggplant, and other produce, is an island in a sea of conventional row crops. “I call this a ‘sub-urban’ farm, a farm that has enough property and land to really produce a lot of food,” Ewer explains on a sweaty July morning. “It all goes back into the Green BEAN channel.” Behind him, “Jimmy”—a chiseled, shirtless man with a beard, straw hat, and dirty jeans, one of five full-time farmhands—races by on a small tractor.

It’s going to take more larger-scale organic “production farms” like this operation in Sheridan, Ewer thinks, for the delivery service to both grow and stay local. And in that regard, Green BEAN might be in luck, at least if recent trends continue. The USDA listed 239 certified-organic operations in Indiana as of 2012—compared to just 132 counted by the 2002 ag census. Jessica Ervin, who works at the Greenwood office of Ecocert ICO (which purchased Indiana Certified Organic in 2009), has seen a “consistent increase” in the number of organic farms in the state, and even some conventional farmers are starting to transition parts of their operations to organic. “It’s a growing sector,” she says. “They can get a premium price for their products because the consumer demand is there.”

Forgoing chemicals and genetically modified seeds—and the long-term health and environmental risks Ewer and Blessing believe those products create—makes for harder work at The Feel Good Farm. But they wouldn’t do it any other way. “We haven’t learned how to make money off this farm yet,” says Ewer. “It’s a long, painful—but beautiful—process. We take great pride in feeding people and helping fix a broken food system.”

This article appeared in the September 2013 issue. Read about more New Hoosier Farmers here.