Phil Gulley: Dead Wrong

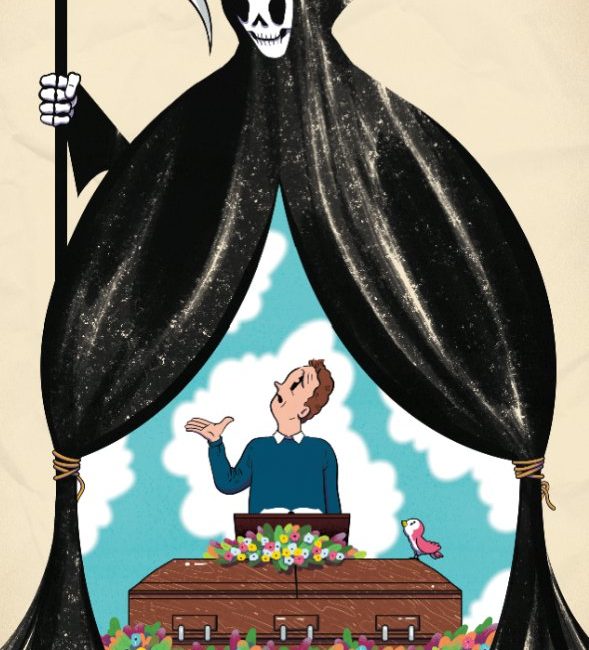

Someone recently asked me whether I liked being a pastor. I’ve been doing it 31 years, so I must enjoy the practice enough to keep at it. Still, no job is perfect, and if I could eliminate one duty in pastoring, it would be funerals. I’ve done several hundred of them, and it hasn’t gotten easier with repetition. I know most of the people I bury, and I hate that they’re dead and I won’t see them again. At the funeral, I often say we’ll see them again in heaven. But I say it with my fingers crossed, because I’m starting to doubt it. I suspect once we’re dead, we’re dead, and that’s the end of things as far as we’re concerned. Heaven is a nice idea. In fact, it’s too nice of an idea, which makes me suspect we made it up.

What bothers me most about funerals is the fraud involved. I’ve buried quite a few stinkers these past 31 years, but you would never have known it from their funerals. No matter how bad they were, their families wanted only nice things said about them. The mortician made them look better than they had looked when alive, filling their bodies with chemicals to make it seem as if they’d stretched out for a nap and would be waking any minute to eat supper. Supper is often what killed them, clogging their arteries with fat and plaque, though we would never say that at their funeral. Instead, we wonder aloud why God decided to “take them home.” Most of the time, God had nothing to do with it.

I can’t count the times I’ve done a funeral for a chain-smoker only to have someone approach me afterward, baffled by the cause of death. I want so badly to say, “Uh, he ate everything in sight, smoked like a chimney, and hadn’t exercised since eighth-grade gym class.” Of course, ministers who say that don’t last 31 years. So I shake my head as if I too am puzzled by this startling development, and say it is too great a mystery for us mortals to understand.

Another fraud we perpetrate is our denial of death, our refusal to even utter the word. We never say someone died. We say they passed on, or went to a better place, or were laid to rest. I once heard a minister say someone had awakened to eternal life. Doesn’t that sound just like a minister? I’ll admit it’s more poetic than the time my dad said the widow down the street was deader than a mackerel, though for the sake of precision, I prefer my father’s version.

Several times a week, I get a phone call asking me to perform the funeral of a person who never attended church. It’s always those folks who expect the most from the church when someone dies—the pastor’s full and immediate attention, the flowers, the choir, the trumpet entrance into heaven, the elaborate family dinner afterward. It’s like they’re trying to trick God into letting someone into heaven who never showed the least interest in going there.

An emerging trend in funerals that I find encouraging is the growing realization that you don’t have to have a pastor at a service in order to bury someone. A close friend or family member is more than sufficient and will have known the dead person better anyway. The best eulogy I ever heard was given by an attorney at the funeral of his friend, a fellow attorney. It was heartfelt, eloquent, and both humorous and respectful, which isn’t easy to pull off. When the minister stood to speak, things went south in a hurry. He babbled on and on about someone he barely knew, told one canned story after another, and then cracked a few stale jokes. I was embarrassed to be in the same profession.

The modern funeral has its roots in the Civil War, when soldiers killed on distant battlefields were embalmed so they could be shipped home. By the time Abraham Lincoln died, the technique had advanced enough to take him on a road show, through seven states for 12 funerals, where millions of people gawked at him. Morticians went along to dab makeup on him when his skin turned black. After Lincoln’s death, everyone wanted to be embalmed. The tradition is only now losing steam with the rise of cremation. It makes a lot more sense to say “ashes to ashes, dust to dust” when someone is actually ashes. It made no sense when people were mostly formaldehyde, turning the average cemetery into a toxic dump.

When I was a kid, I saw an episode of Gunsmoke in which a dead Indian chief was placed on an elevated platform and left there. I remember being intrigued by that. There are some places it wouldn’t work; in large cities, for instance, it wouldn’t behoove us to leave bodies outside to rot. But I have a farm in Southern Indiana, and if my wife and sons hauled my carcass out to the woods there and propped me against a tree, I wouldn’t mind. Or they could set me on fire. I don’t care. I won’t feel a thing.

The average funeral now costs around $10,000, including the headstone and burial plot. That happens to be the median income worldwide. It seems wasteful to spend someone’s annual income to bury a person. It would be cheaper if we didn’t have to hire morticians. Indiana (wouldn’t you know it) is one of the few states that require a funeral director be used. That ought to tell you something about the lobbying power of your friendly neighborhood mortician. I’m thinking of asking the legislature to require Hoosiers to buy my books.

Being a pastor, I’ve spent my whole life trying to make people happy, so when I die, it’s going to be time others made me happy. They can start by paying the mortician so my wife won’t have to. I’ve told her to take up an offering during my funeral and not let anyone leave until they’ve kicked in $50. I haven’t been all that good with money, and she’s going to need some help. People will feel better about paying for my funeral if I’m killed doing something heroic, so my wife will have to make up a good story. I’ll probably die from eating too much bacon, but if you hear that I got hit by a train while rescuing a little girl and her puppy, don’t be surprised.