The New Hoosier Farmer: Keeps His Animals Happy

Entrepreneur Chris Baggott didn’t make a small fortune by shying away from risk. “I love when someone tells me that I can’t do something,” he says. “That’s what drives me.”

In 2000, at the height of the dot-com crash, he co-founded Indianapolis-based software firm ExactTarget. Then he read The Omnivore’s Dilemma, the bestselling indictment of modern factory farming. Inspired, he took an early retirement and, in 2010—just a year after ExactTarget surpassed $100 million in annual sales—purchased a 98-acre farm near Greenfield to raise livestock. Never mind that he had no agricultural experience whatsoever.

Baggott might have argued that in Indiana, raising livestock—pigs, in particular—is good business. In 2005, the Indiana Department of Agriculture, under the newly elected Governor Mitch Daniels, announced a plan to double the state’s pork production, in part by creating a friendly economic environment for “confined” and “concentrated” animal-feeding operations (CFOs and CAFOs), industrial facilities with pigs housed in feeding barns and typically given a diet of mostly corn or soybean meal, supplemented with antibiotics. By 2007, Indiana hog sales had increased by more than a million animals since 2002—and the number of pig farms had decreased by nearly a thousand. CAFOs and consolidation were rapidly reshaping the state’s pig production and fattening pocketbooks: From 2007 to 2011, the average value of hog sales grew by more than half, exceeding $1 billion annually.

Baggott, along with business partner Daniel “Duffy” Farrell, a pressman from The Indianapolis Star, wanted to go against the grain, so to speak. CAFOs are “exactly what’s wrong with the industry,” says Baggott. “Our big fight is getting people to learn more about local food and the nuances of where pork is raised and what it ate. Every animal we raise tastes different.”

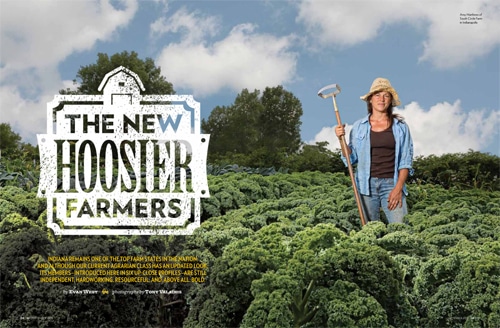

Their venture, Tyner Pond Farm, resembles the Old McDonald Farm you might have imagined as a child. Cattle, pigs, and chickens spend their days in the open air, grazing, rooting, and pecking around in pastures. They sleep in little red barns. The eponymous pond provides an irrigation source (as well as a fishing hole).

“It’s kind of a laboratory,” says Baggott. “What we are trying to prove is the economic sustainability of this kind of farming.”

A year into the business, Farrell died in a motorcycle accident. His brother, Mark, took up Daniel’s end of the partnership. Now, Tyner Pond is a family farm in the old-fashioned sense. Both the men’s broods can be found there on most summer days. Baggott’s and Farrell’s sons have part-time jobs delivering meat.

Absent experience, Baggott and Farrell have learned as they go, visiting other farms and watching online tutorials. And while the setting has a distinctly 19th-century vibe, Baggott—who still runs Compendium, another software company—isn’t averse to using technology. One innovation in particular, polywire, has been a game-changer. Land needs recovery time after heavy grazing, meaning animals must be moved to different pastures throughout the year. In contrast to permanent fencing, the electrified, easy-to-restring polywire allows Tyner Pond to quickly and cheaply divide grazing areas. “This all doesn’t work without polywire,” says Baggott. “Grandpa couldn’t do what we are doing.”

Baggott and Farrell rely on online sales and direct deliveries to individual customers around Central Indiana. They still lose money some months, but those have become fewer and farther between. And they have no surplus, which Baggott attributes to the quality of free-range meat and consumer demand for local products.

“It’s kind of a laboratory,” he says. “What we are trying to prove is the economic sustainability of this kind of farming, and hopefully educate and show others that there is an alternative.”

This article appeared in the September 2013 issue. Read about more New Hoosier Farmers here.